Sources

1) Levin Dov. 2006. Šeduva. In.Pinkas ha-kehilot. Lita (Encyclopaedia of Jewish Communities. Lithuania). Jerusalem. Pp.654-658.

2) Greenberg Masha. 1995. The Jews of Lithuania: A History of a Remarkable Community, 1316-1945. Jerusalem.

3) Jewish Life in Lithuania: Exhibition Catalogue. 2001. Vilnius.

4) Presentation by Anat Rosen for the Shadova - Šeduva reunion at Kefar Sirkin in April 2008. Photographs by Nosson, Peter Arnold, Sara Keter, Nava Shulkin, Tamara and Raanan Reshef. Additional pictures courtesy of Nava Shulkin.

5) Shtetlink site for Shadova - Šeduva by Dora Boom.

6) Website pages referenced are linked throughout the text.

Please note that this article is not primary research and it may contain errors. Feel welcome to to suggest corrections.

1) Levin Dov. 2006. Šeduva. In.Pinkas ha-kehilot. Lita (Encyclopaedia of Jewish Communities. Lithuania). Jerusalem. Pp.654-658.

2) Greenberg Masha. 1995. The Jews of Lithuania: A History of a Remarkable Community, 1316-1945. Jerusalem.

3) Jewish Life in Lithuania: Exhibition Catalogue. 2001. Vilnius.

4) Presentation by Anat Rosen for the Shadova - Šeduva reunion at Kefar Sirkin in April 2008. Photographs by Nosson, Peter Arnold, Sara Keter, Nava Shulkin, Tamara and Raanan Reshef. Additional pictures courtesy of Nava Shulkin.

5) Shtetlink site for Shadova - Šeduva by Dora Boom.

6) Website pages referenced are linked throughout the text.

Please note that this article is not primary research and it may contain errors. Feel welcome to to suggest corrections.

The Jews of Shadova - Šeduva

The Jewish Community of Shadova - Šeduva

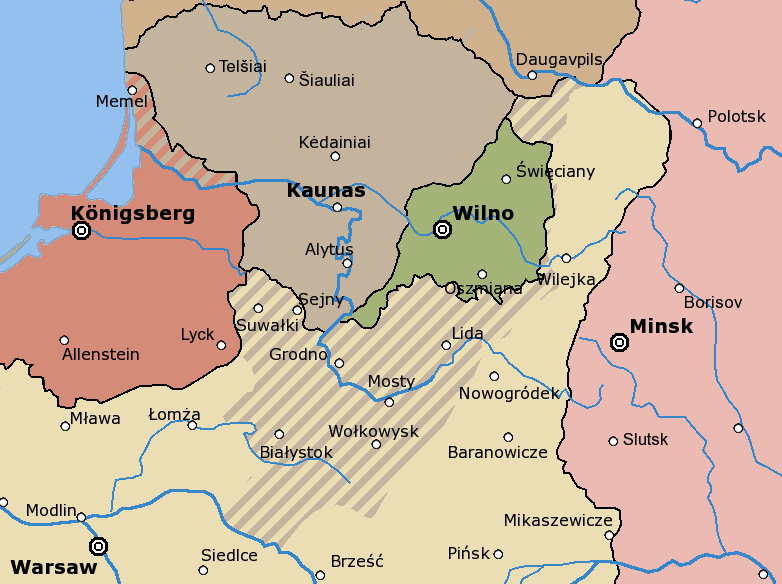

Click Map Inset to Enlarge

Family Locations Underlined

Map of Lithuania - The Family Shtetls and Towns are Underlined

Koenigsburg (Kaliningrad), Kretinga, Shadova, Kraslava

Koenigsburg (Kaliningrad), Kretinga, Shadova, Kraslava

Litvaks - The Jews of Lithuania

Jews, probably refugees from the Near East, settled the lands between the Baltic and Black Sea that would become part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, as early as the eighth century. However, a later and much larger immigration originated in the twelfth century as a consequence of Crusader persecutions. Yiddish, the traditional language of Lithuanian Jews, is based largely upon the Medieval German and Hebrew spoken by these western Germanic Jewish immigrants. The first Jewish settlers moved to cities which later became the important centers of Jewish life in Lithuania. Grodno, one of the oldest, was first mentioned in the chronicles of 1128. By the 14th century major Jewish centres are documented at Novogrudok (Navahrudak), Kerlov, Voruta, Twiremet; Eiragola; Golschany, Kovno (Kaunas), Telshe (Telz, Telsiai), Vilna (Vilnius), Lida, and Trakai.

With Gediminas' campaign of expansion in 1320 the Jews were encouraged to settle throughout the northern provinces of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The Jews enjoyed considerable prosperity and influence, taking an active part in the development of the new cities under the tolerant rule of Gediminas.

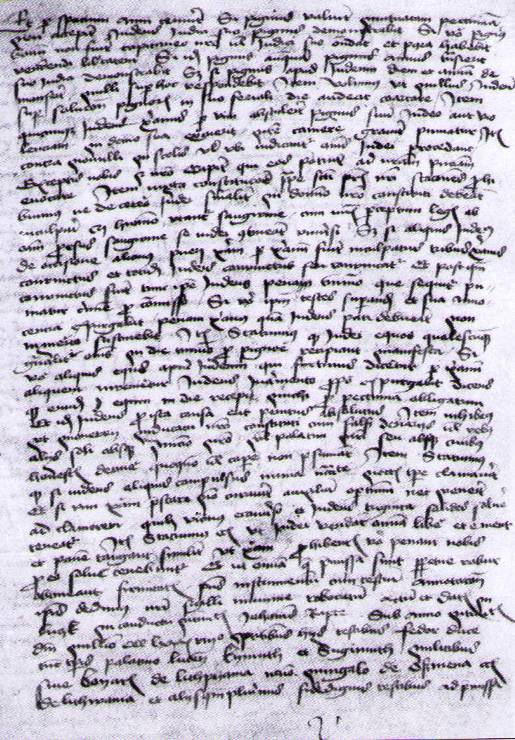

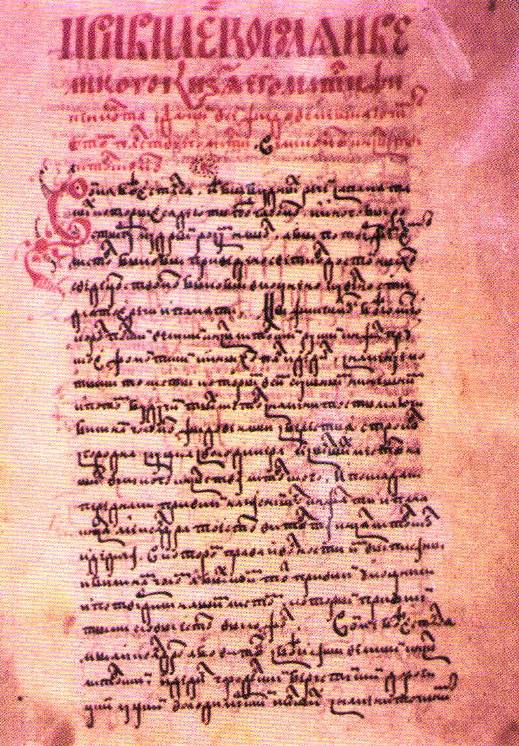

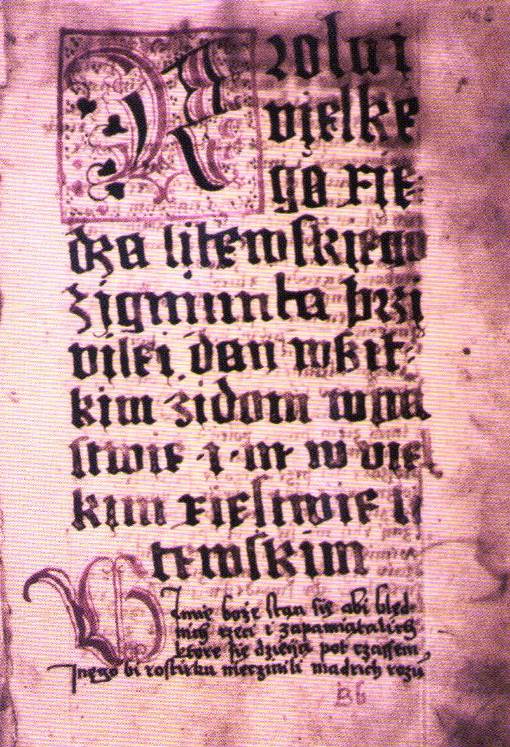

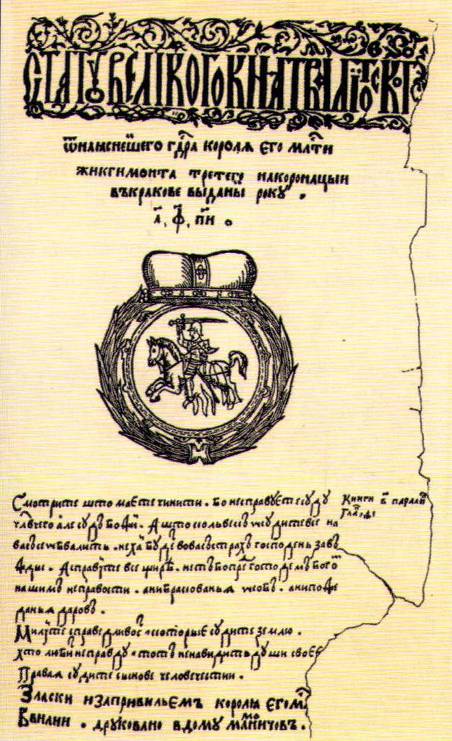

The formative charter of privileges issued by Vytautas in 1341 was momentous for the subsequent history of the Jews of Lithuania.

Jews, probably refugees from the Near East, settled the lands between the Baltic and Black Sea that would become part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, as early as the eighth century. However, a later and much larger immigration originated in the twelfth century as a consequence of Crusader persecutions. Yiddish, the traditional language of Lithuanian Jews, is based largely upon the Medieval German and Hebrew spoken by these western Germanic Jewish immigrants. The first Jewish settlers moved to cities which later became the important centers of Jewish life in Lithuania. Grodno, one of the oldest, was first mentioned in the chronicles of 1128. By the 14th century major Jewish centres are documented at Novogrudok (Navahrudak), Kerlov, Voruta, Twiremet; Eiragola; Golschany, Kovno (Kaunas), Telshe (Telz, Telsiai), Vilna (Vilnius), Lida, and Trakai.

With Gediminas' campaign of expansion in 1320 the Jews were encouraged to settle throughout the northern provinces of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The Jews enjoyed considerable prosperity and influence, taking an active part in the development of the new cities under the tolerant rule of Gediminas.

The formative charter of privileges issued by Vytautas in 1341 was momentous for the subsequent history of the Jews of Lithuania.

This document, and later similar decrees of privilege, were granted first to the Jews of Brisk (Brest-Litovsk) in 1388, and later in other towns. They recognise distinct, often autonomous, organisation for Lithuanian Jews known as the Kahal. The charter itself was modeled upon similar documents confered earlier by Boleslaw of Kalisz and Casimir the Great to the Jews in Poland.

The preamble of the charter reads as follows:

The preamble of the charter reads as follows:

Grand Dukes of Lithuania - Gediminas & Vytautas the Great

Vytautas Charters Granting Privileges to the Jews of Lithuania

'In the name of God, Amen. All deeds of men, when they are not made known by the testimony of witnesses or in writing, pass away and vanish and are forgotten. Therefore, we, Alexander, also called Vytautas, by the grace of God Grand Duke of Lithuania and ruler of Brest, Dorogicz, Lutsk, Vladimir, and other places, make known by this charter to the present and future generations, or to whomever it may concern to know or hear of it, that, after due deliberation with our nobles we have decided to grant to all the Jews living in our domains the rights and liberties mentioned in the following charter.'

Under the charter, Lithuanian Jews formed a class of freemen subject in all criminal cases directly to the jurisdiction of the grand duke and his official representatives, the elder (starosta), known as the 'Jewish judge' (judex Judaeorum), and his deputy. His duties included the protection of Jews, their property and their freedom of worship. In matters of religion the Jews were given extensive autonomy. Under these equitable laws the Jews of Lithuania achieved a previously unknown level of prosperity.

Jewish communities were represented by elders, who secured new privileges, and regulated taxes. The elder acted in conjunction with the rabbi, whose jurisdiction included all Jewish affairs with the exception of judicial cases assigned to the court of the deputy, and by the latter to the king. The chazan (cantor), gabai (sexton), and shochet (ritual slaughterer) were subject to the orders of the rabbi and elder.

Jewish communities were represented by elders, who secured new privileges, and regulated taxes. The elder acted in conjunction with the rabbi, whose jurisdiction included all Jewish affairs with the exception of judicial cases assigned to the court of the deputy, and by the latter to the king. The chazan (cantor), gabai (sexton), and shochet (ritual slaughterer) were subject to the orders of the rabbi and elder.

Waves of Prosperity and Exclusion - The Polish - Lithuanian Union

With the rise of the Jagiellon dynasty in 1386 Poland and Lithuania the Jews were brought the under unitary rule, the Kings of Poland and Dukes of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania confirming in turn the charter of privileges granted to the Jews by their predecessors. This was a period of general prosperity and relative safety for the Jews of both countries, marred by a decree promulgated by Alexander in 1495, through which all Jews living in Lithuania Properia and the adjacent territories were summarily expelled, and their property confiscated to fill the depleted treasury. Though some of the exiles migrated to the Crimea, most settled in towns along the Polish-Lithuanian border. By 1503 Alexander permitted the exiles to return, and restituted their houses, lands, synagogues, cemeteries, property and old debts.

During the 16th century antagonism developed between the szlachta (lesser nobility) and the Jews, primarily due to causes engendered by economic competition, but utilised by the Catholic clergy in their crusade against heretics, notably the Lutherans, Calvinists, and Jews. Since the Jews lived in the towns and on the lands of the king, the nobility could not wield any authority over them nor derive profit from them. At the Diet of Vilna of 1551 the szlachta imposition of a poll tax of one ducat per Jew, and demanded that Jewish tax-collectors be forbidden to erect tollhouses or place guards at the taverns on their estates at the Kings behest. The anti-semitic legislation of 1566 extended to the prohibition of Jews from wearing wear costly clothing and jewelry, requiring them to wear distinctive

With the rise of the Jagiellon dynasty in 1386 Poland and Lithuania the Jews were brought the under unitary rule, the Kings of Poland and Dukes of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania confirming in turn the charter of privileges granted to the Jews by their predecessors. This was a period of general prosperity and relative safety for the Jews of both countries, marred by a decree promulgated by Alexander in 1495, through which all Jews living in Lithuania Properia and the adjacent territories were summarily expelled, and their property confiscated to fill the depleted treasury. Though some of the exiles migrated to the Crimea, most settled in towns along the Polish-Lithuanian border. By 1503 Alexander permitted the exiles to return, and restituted their houses, lands, synagogues, cemeteries, property and old debts.

During the 16th century antagonism developed between the szlachta (lesser nobility) and the Jews, primarily due to causes engendered by economic competition, but utilised by the Catholic clergy in their crusade against heretics, notably the Lutherans, Calvinists, and Jews. Since the Jews lived in the towns and on the lands of the king, the nobility could not wield any authority over them nor derive profit from them. At the Diet of Vilna of 1551 the szlachta imposition of a poll tax of one ducat per Jew, and demanded that Jewish tax-collectors be forbidden to erect tollhouses or place guards at the taverns on their estates at the Kings behest. The anti-semitic legislation of 1566 extended to the prohibition of Jews from wearing wear costly clothing and jewelry, requiring them to wear distinctive

Alexander Jagiellon & Sigismund II Augustus

Szlachta - The Nobles of Poland-Lithuania

clothing and yellow caps and kerchiefs. Sigismund II Augustus, the first king of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, checked the repressive measures and reaffirmed the old charters for the 120000 Jews of Lithuania.

The Cossacks Uprising and the

Demise of the Polish - Lithuanian Commonwealth

Jewish life in Lithuania would be shattered by the massacres of the Khmelnytsky Uprising between 1648-1657. What had commenced as a Cossack rebellion commanded by Hetman Bogdan Khmelnytsky against Polish supremacy, developed into pitch battles against the army of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Polish nobles commonly sold and leased their estates to Jewish renters for a percentage of its revenue, while they reveled at court. The Jewish leaseholders became the proxy objects of hatred to the oppressed peasantry, incited by Khmelnytsky who told the people that the Poles had sold them as slaves "into the hands of the accursed Jews."

The result of the insurgence was an eradication of the control of the Polish szlachta, their Jewish intermediaries, and the end of Catholic ecclesiastical domination. During the rebellion the Cossacks and the peasantry massacred up to 100000 Jews, half of the Jewish population of the Commonwealth. The fury of the uprising destroyed the communal organisation and left the survivors practically destitute. Jan Casimir (1648-1668) sought to alleviate the situation by granting concessions to the Jewish communities of Lithuania. However, efforts to resurrect the old power structure of the kahals were not successful, and the impoverished communities became indebted to the clergy and the nobility.

But by 1792 the Jewish population of Lithuania had grown to an estimated 250000. The Jews were especially active in commerce and industry, while the nobles continued to earn their living from their estates and farms, some of which were managed by Jewish leaseholders, and city properties were concentrated in the possession of monasteries, churches, and the lesser nobility. The final collapse of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the gradual partition of Poland brought Lithuania under Czarist Russian control in 1793 and 1795.

Demise of the Polish - Lithuanian Commonwealth

Jewish life in Lithuania would be shattered by the massacres of the Khmelnytsky Uprising between 1648-1657. What had commenced as a Cossack rebellion commanded by Hetman Bogdan Khmelnytsky against Polish supremacy, developed into pitch battles against the army of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Polish nobles commonly sold and leased their estates to Jewish renters for a percentage of its revenue, while they reveled at court. The Jewish leaseholders became the proxy objects of hatred to the oppressed peasantry, incited by Khmelnytsky who told the people that the Poles had sold them as slaves "into the hands of the accursed Jews."

The result of the insurgence was an eradication of the control of the Polish szlachta, their Jewish intermediaries, and the end of Catholic ecclesiastical domination. During the rebellion the Cossacks and the peasantry massacred up to 100000 Jews, half of the Jewish population of the Commonwealth. The fury of the uprising destroyed the communal organisation and left the survivors practically destitute. Jan Casimir (1648-1668) sought to alleviate the situation by granting concessions to the Jewish communities of Lithuania. However, efforts to resurrect the old power structure of the kahals were not successful, and the impoverished communities became indebted to the clergy and the nobility.

But by 1792 the Jewish population of Lithuania had grown to an estimated 250000. The Jews were especially active in commerce and industry, while the nobles continued to earn their living from their estates and farms, some of which were managed by Jewish leaseholders, and city properties were concentrated in the possession of monasteries, churches, and the lesser nobility. The final collapse of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the gradual partition of Poland brought Lithuania under Czarist Russian control in 1793 and 1795.

Bogdan Khmelnytsky

Reply of the Cossacks to the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed IV

Ilya Repin, 1880-1891

Ilya Repin, 1880-1891

Jan Casimir Vasa

Lithuanian Jews under the Russian Empire

Under Russian hegemony the Jews were restricted to a large area, known as the Pale of Settlement, that included all of Lithuania. Russia conducted a policy of Russification aimed at all the minority groups. For Jews this oscillated between persecution and attempts at assimilation, leading many to adopt Russian language and customs. Independent Jewish life ended finally in 1844 when the civil authority of the Jewish Councils of Elders (Kehilla) was

Rabbi Elijah ben Solomon (1720-1797), known as the Vilna Gaon or the Gra, was an exceptional Talmudist, Halachist, and Kabbalist, and the foremost leader and intellectual of non-hasidic orthodox Jewry.

He wrote numerous volumes concentrating on commentary of the Talmud and the Shulchan Aruch known as Biurei ha-Gra, the Mishnah - Shenoth Eliyahu and the Torah - Adereth Eliyahu. With the growing influence of Hasidism the Gra joined other rabbis known as the Mitnagdim, to curb their impact.

In later life the Gra encouraged his pupil, Rabbi Chaim Volozhin, to found a yeshiva to teach Torah and Talmud the Lithuanian analytical style still practiced in most yeshivot. The Volozhin yeshiva became the model for the famous Lithuanian seminaries at Ponevezh, Telshe, Mir, Kelm, and Slabodka. The characteristic Litvak approach to Judaism was marked by a concentration on highly intellectual Talmud study. Though Lithuania became synonymous with the mitnagdim it must be remembered that many Litvaks followed Hasidism, most belonging to the Chabad, Slonim and Karlin-Pinsk courts.

It can be claimed that this tradition of Litvak learning would lead many to become keen devotees of the Haskala movement in Eastern Europe, many of their descendents today becoming leading academics, scientists and philosophers.

He wrote numerous volumes concentrating on commentary of the Talmud and the Shulchan Aruch known as Biurei ha-Gra, the Mishnah - Shenoth Eliyahu and the Torah - Adereth Eliyahu. With the growing influence of Hasidism the Gra joined other rabbis known as the Mitnagdim, to curb their impact.

In later life the Gra encouraged his pupil, Rabbi Chaim Volozhin, to found a yeshiva to teach Torah and Talmud the Lithuanian analytical style still practiced in most yeshivot. The Volozhin yeshiva became the model for the famous Lithuanian seminaries at Ponevezh, Telshe, Mir, Kelm, and Slabodka. The characteristic Litvak approach to Judaism was marked by a concentration on highly intellectual Talmud study. Though Lithuania became synonymous with the mitnagdim it must be remembered that many Litvaks followed Hasidism, most belonging to the Chabad, Slonim and Karlin-Pinsk courts.

It can be claimed that this tradition of Litvak learning would lead many to become keen devotees of the Haskala movement in Eastern Europe, many of their descendents today becoming leading academics, scientists and philosophers.

The Gaon from Vilna & the Misnagdim

The Vilna Gaon

The Great Synagogue of Vilna

The Volozhin and Telshe (Telz) Yeshivot

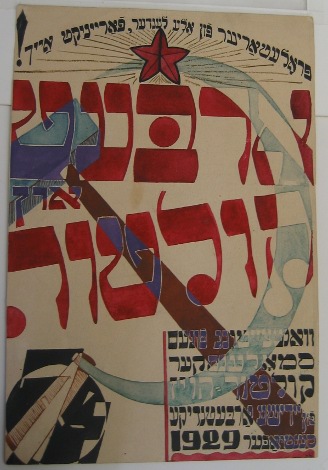

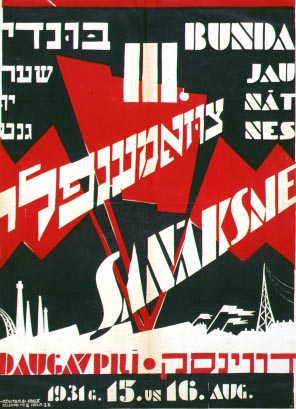

Ideas to oust the repressive Czarist regime were attractive and many Jews were active in Russian revolutionary parties. In 1897 the General Jewish Labour Bund ( xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx ) was formed in Vilna to "unite all Jewish workers in the Russian Empire into a united socialist party", with the vision of seeing Jews achieve recognition as a nation with legal minority status in their place of residence, promoted the use of Yiddish as a Jewish national language. The Bund strongly opposed Zionism, viewing emigration to Palestine was a form of escapism. Together with Socialist Zionists the Bund formed self-defense organisations to protect Jewish communities against pogroms and government troops.

Czar Alexander III

secondary and higher education, restricted Jews from practicing many professions, limited residence to larger towns and prohibited Jews from participation in local elections. Persecution, and perceived good economic opportunities, provided the impetus for the mass emigration of more than two million Jews who left Russia between 1880 and 1920. Thousands of Litvaks emigrated to the United States of America and a small number made Aliyah to Palestine as members Hovevei Zion. A popular desination was South Africa, which became a haven for 120000 Lithuanian Jews.

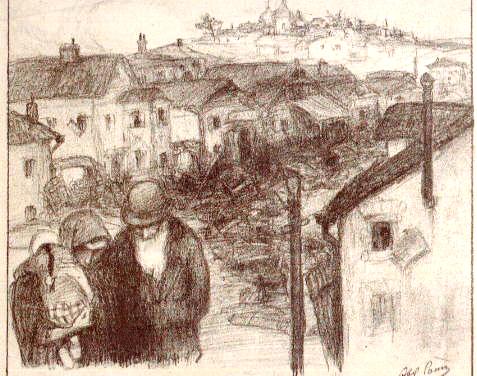

After the Pogrom - Abel Pann

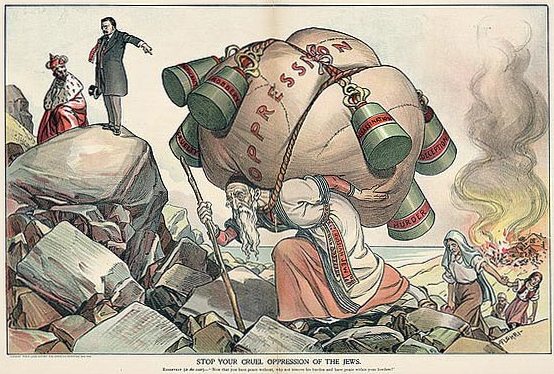

Protest of Czarist Oppression - 1904

New Ideologies - Zionism, Bundism and Folkism

Lithuanian Jews found ideological expression for their opposition to their oppression though massive involvement in both Zionist and revolutionary movements.

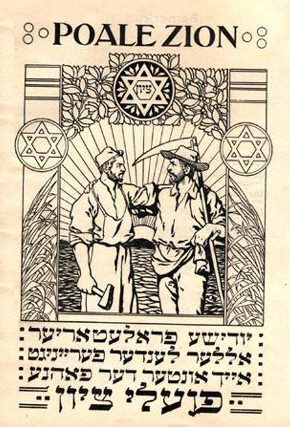

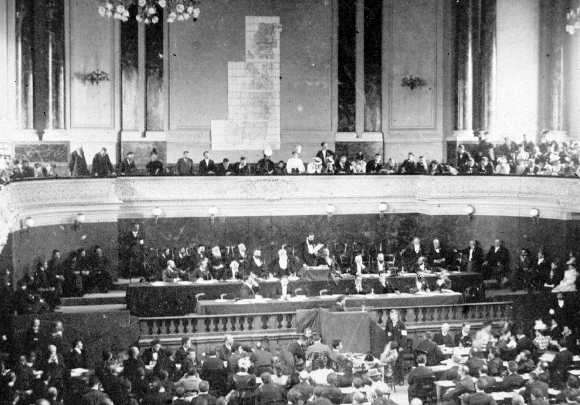

The first organised Zionist movements were of Hovevei Zion, based on Pinsker's ideas of rejection of the Ghetto and 'Auto-emancipation'. Associations were established throughout Lithuania prior to the first Zionist Congress in 1897. Vilna became one of the most important centers of Russian Zionism at the beginning of the twentieth century and the religious Zionist movement Mizrahi was established there in 1902, while the socialist Zionist movement Poale Zion became popular, combining Zionism with the

Lithuanian Jews found ideological expression for their opposition to their oppression though massive involvement in both Zionist and revolutionary movements.

The first organised Zionist movements were of Hovevei Zion, based on Pinsker's ideas of rejection of the Ghetto and 'Auto-emancipation'. Associations were established throughout Lithuania prior to the first Zionist Congress in 1897. Vilna became one of the most important centers of Russian Zionism at the beginning of the twentieth century and the religious Zionist movement Mizrahi was established there in 1902, while the socialist Zionist movement Poale Zion became popular, combining Zionism with the

officially abolished. Policies towards the Jews were the result of the views of each Czar in turn, marked by the extreme anti-Semitism of Czar Alexander III. His escalation of anti-Jewish policies, and popularisation of folk anti-Semitism were the agent for a wave of pogroms that swept Russia in 1881, and again between 1903 and 1906. Thousands of Jewish homes were destroyed, and many Jews were injured killed with tacit government knowledge and even incitement. This was accompanied by systematic but capricious policies that placed quotas on places for

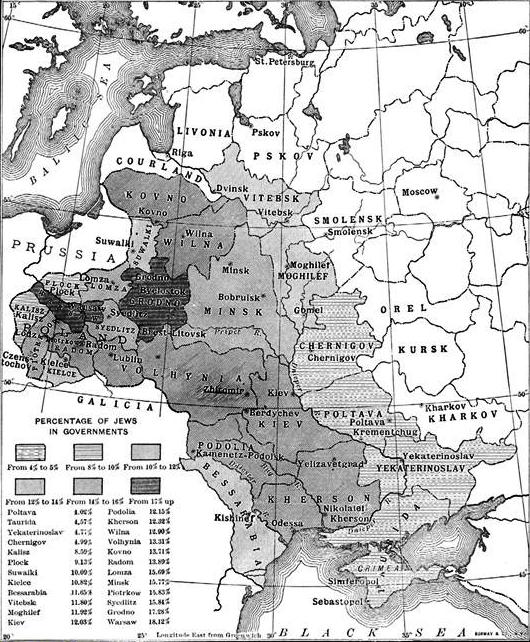

The Pale of Settlement

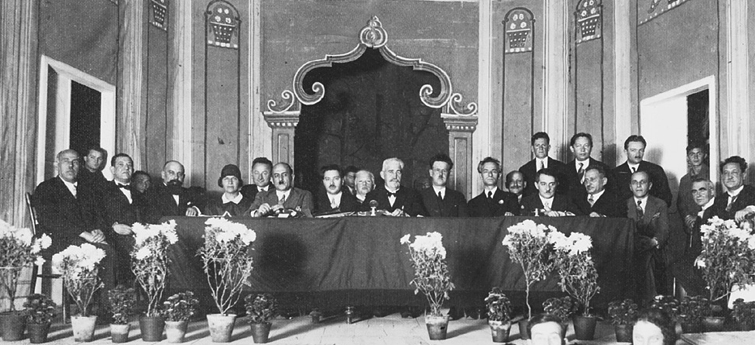

Chaim Weizman and the Second Zionist Congress at Basel

Socialist Zionist Posters of Poale Zion

Shimon Rosenbaum & Jakub Wygodzki

Lithuanian and other Russian Zionists gave support to synthetic Zionism as advanced by Chaim Weizman, working dually for Jewish rights and Aliyah to Eretz Israel, together with work in the Diaspora to improve conditions for the Jewish masses in their place of birth. At the end of 1905 Vilna became the organisational centre for the whole Russian Zionist movement, and until 1911 its central bureau was located there.

Regarded as 'potential' German spies during WWI, many Zionists were exiled by tsarist decree to the Russian interior. Those remaining in German-occupied territory attempted to promote cultural activity and to organise Hebrew education. At the wars end opinions about cooperation with Lithuanians diverged. After long negotiations and delays, the first Lithuanian Zionist conference took place in Vilna on December 5-8, 1918. It was decided that all active Zionist organizations unite to form one Zionist Union of Lithuania. A pro-Lithuanian orientation, supporting the establishment of an independent Lithuanian state, was promoted by Shimon Rosenbaum and Jakub Wygodzki who joined the ranks of the nationalist assembly or Taryba.

Regarded as 'potential' German spies during WWI, many Zionists were exiled by tsarist decree to the Russian interior. Those remaining in German-occupied territory attempted to promote cultural activity and to organise Hebrew education. At the wars end opinions about cooperation with Lithuanians diverged. After long negotiations and delays, the first Lithuanian Zionist conference took place in Vilna on December 5-8, 1918. It was decided that all active Zionist organizations unite to form one Zionist Union of Lithuania. A pro-Lithuanian orientation, supporting the establishment of an independent Lithuanian state, was promoted by Shimon Rosenbaum and Jakub Wygodzki who joined the ranks of the nationalist assembly or Taryba.

revolutionary fervor of Marxism during this critical period.

Within a short period the Zionist movement in Lithuania broke into competing political factions represented by General, Social, Religious and Revisionist trends. Its separate branches spread very quickly and were active even in the smaller shtetls.

The socialist Zionist movement was represented by the 'Zairei Zion' youth who were associated with the underground 'Poale Zion', which gave reason to the Lithuanian authorities to suspect the whole socialist Zionist faction and, after the military coup in 1926, to close down its organisations. But the socialist Zionists consolidated their position, and as the numbers of delegates to Zionist congresses show, they were the most influential Zionist faction in Lithuania.

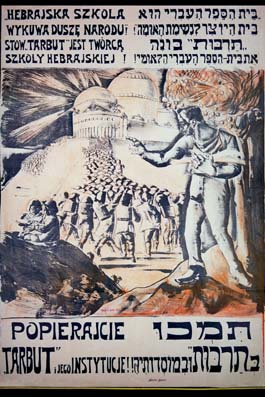

The Zionist organization made every effort to institute Jewish autonomy in Lithuania, attempted to represent their interests on municipal councils and in general elections, often on joint lists with other Jewish factions. The Zionists worked for a legal settlement of the issue of Hebrew language teaching through the Zionist 'Tarbut' school system.

Especially active was the 'HeHalutz' (Pioneer) movement whose aim was the preparation of youth for Aliya and a new life in Palestine, training youth spiritually, ideologically, physically, and professionally for agricultural work. Hechalutz established numerous 'Kibbutzim' throughout Lithuania in order to achieve its goals. Despite the poor political and economic situation in Palestine, numerous Halutzim were attracted by the communal spirit of 'Hehalutz', competing for the limited the number of Certificates available for emigration to Palestine.

The socialist Zionist movement was represented by the 'Zairei Zion' youth who were associated with the underground 'Poale Zion', which gave reason to the Lithuanian authorities to suspect the whole socialist Zionist faction and, after the military coup in 1926, to close down its organisations. But the socialist Zionists consolidated their position, and as the numbers of delegates to Zionist congresses show, they were the most influential Zionist faction in Lithuania.

The Zionist organization made every effort to institute Jewish autonomy in Lithuania, attempted to represent their interests on municipal councils and in general elections, often on joint lists with other Jewish factions. The Zionists worked for a legal settlement of the issue of Hebrew language teaching through the Zionist 'Tarbut' school system.

Especially active was the 'HeHalutz' (Pioneer) movement whose aim was the preparation of youth for Aliya and a new life in Palestine, training youth spiritually, ideologically, physically, and professionally for agricultural work. Hechalutz established numerous 'Kibbutzim' throughout Lithuania in order to achieve its goals. Despite the poor political and economic situation in Palestine, numerous Halutzim were attracted by the communal spirit of 'Hehalutz', competing for the limited the number of Certificates available for emigration to Palestine.

'Tarbut' Zionist Hebrew Schools

The Hebrew school is a cry for the soul of the Nation. 'Tarbut' is building the Hebrew National school.

The Hebrew school is a cry for the soul of the Nation. 'Tarbut' is building the Hebrew National school.

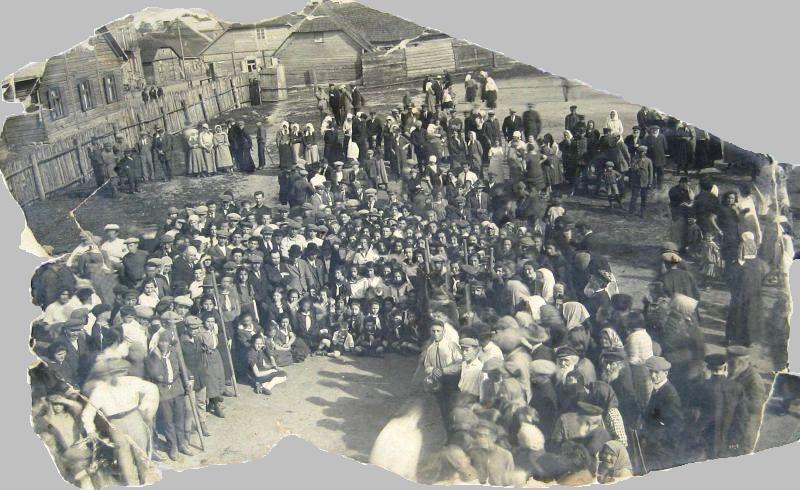

HeHalutz Members at the 'Kibbutz HaCovesh' Farm in Šeduva

Thirtieth Anniversary of the Bund in Vilna & Bundist Poster

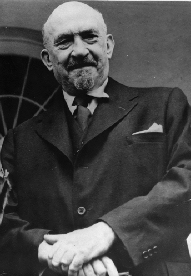

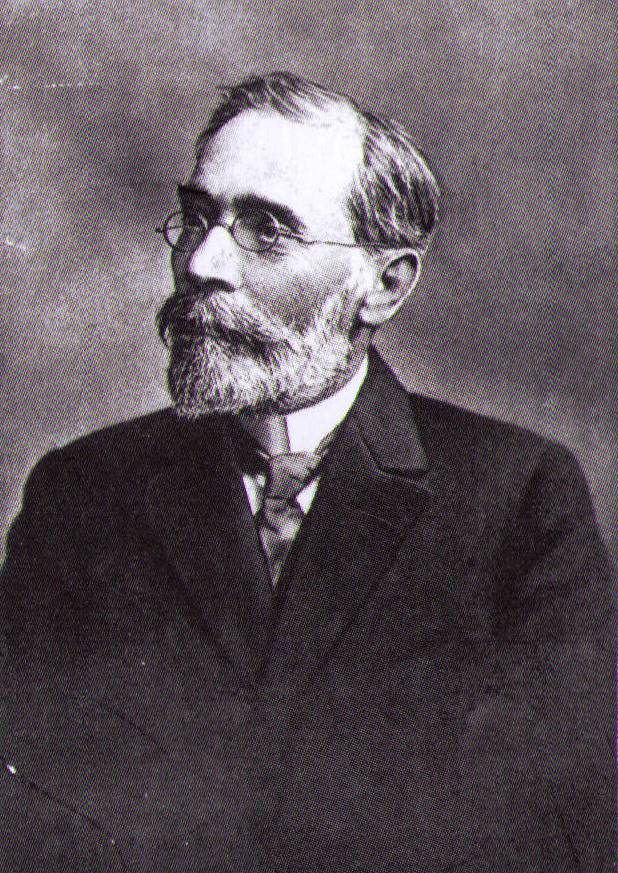

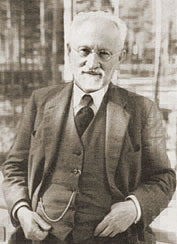

Simon Dubnow

Historian and founder of the Folkspartei

Historian and founder of the Folkspartei

Jewish Communists

Proletariat of all the lands, Unite!

Proletariat of all the lands, Unite!

Another active Yiddisheit party was the liberal Folkspartei (Jewish People's Party) ( xxxxx xxxxxx ) founded after the 1905 pogroms by Simon Dubnow and Israel Efrojkin. The party participated in elections in Poland and Lithuania in the 1920s and 1930s. According to Dubnow (1860-1941), Jews are a nation on the spiritual and intellectual level and should strive towards their national and cultural autonomy in the diaspora (galuth) through a secularised and modernised version of the Council of Four Lands under the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In Ponovezh the lawyer and banker Shmuel Landau was elected as the Member of the first Lithuanian Seimas for the Folkspartei on a common Jewish electoral list with the Zionist parties in 1920. In Vilnius, where Jews formed the majority of the population, the Folkspartei sent Zemach Shabad to the Polish Parliament (Sejm).

Independent Lithuania (1918-1940) - The Rise and Fall of Jewish Autonomy

An independent Lithuanian state was declared, with active Jewish support, on 16 February 1918 in Vilna, but the results of the confrontation with Poland would leave Lithuania without its capital and surrounding region and the government was moved to Kovno (Kaunus). Lithuania was home to 153743 Jews, 7.5% of the total population and the largest national minority. In the larger towns the Jewish community was considerable, constituting a third of the larger towns and 29% of the small-town population. The Jewish community of Vilna numbered close to 100000, about 45% of the total with 110 synagogues and 10 yeshivas.

An independent Lithuanian state was declared, with active Jewish support, on 16 February 1918 in Vilna, but the results of the confrontation with Poland would leave Lithuania without its capital and surrounding region and the government was moved to Kovno (Kaunus). Lithuania was home to 153743 Jews, 7.5% of the total population and the largest national minority. In the larger towns the Jewish community was considerable, constituting a third of the larger towns and 29% of the small-town population. The Jewish community of Vilna numbered close to 100000, about 45% of the total with 110 synagogues and 10 yeshivas.

In the early days of the republic Lithuanian policy encouraged Jewish participation to encourage Jewish support from abroad, especially from the United States. The first Vilna cabinet included three Jews, Jakub Wygodzki (Minister for Jewish Affairs), Shimon Rosenbaum (deputy Foreign Minister), and Nahman Rachmilewitz (deputy minister of Commerce). By 1920 Vilna was occupied by General Zeligowski, and the city and district of Vilna became a part of Poland. The Lithuanian government moved to Kovno and Wygodzki was replaced by the Kaunas communal leader and Zionist Max Soloveichik. Under the terms of the peace conference at Versailles, the Jews of Lithuania were guaranteed national and cultural autonomy. A Jewish National Council was appointed and, in conjunction with the Ministry of Jewish Affairs, administered the Jewish autonomous institutions. The community (kehillah) was responsible for the registration of Jewish births and.had the entitlement to impose taxes to support the budgets for religious affairs, charity, social aid and educational institutions, and the like. But as early as 1923 reactionary clerical groups challenged Jewish autonomy and their rights were quickly eroded. The Ministry for Jewish affairs was closed in 1924, the Jewish representative council elected in 1923 was dispersed by the Police and the local kehillot were also dissolved. The only remnants of autonomy were the Jewish people's banks and the Hebrew or Yiddish school system.

In fact the educational system was one of the most important achievements of the Jewish national autonomy. The cost was initially borne by the state and three school systems flourished: the Zionist Hebrew language Tarbut schools; the socialist-Yiddisheit schools and the religious schools of the Yavneh network. In addition there were also traditional Cheder, Talmud Torah and Yeshivot (see above). Jewish students had been a significant part of the student body of the universities but the gradual introduction of the numerus clausus meant that by 1936 no Jews were admitted to learn medicine and the proportion of Jewish students in the other faculties fell sharply. Also associated with the educational system was YIVO - the Jewish Scientific Institute established in Vilna in 1925 to document Jewish life, history and culture.

Jews were also elected to the Lithuanian national assembly (Seimas), six in 1920, and seven in 1923. As minority rights were eroded, Jewish (and Polish) representation dropped. In 1926 a military coup d'etat led to the establishment of an authoritarian government under Antanas Smetona of the extremist nationalist Tautininkai. Agrarian reform, and the government assisted formation of cooperatives to control trade, affected especially Jewish traders. Most small Jewish shops were unable to compete with the Lithuanian cooperatives, which enjoyed great privileges especially in respect of taxation. The economic position of the Jewish population became increasingly precarious, especially in face of the anti-Semitic campaign of 'Verslininkai', an organisation of Lithuanian traders and workers, using the slogan 'Lithuania for Lithuanians' who led a campaign to boycott Jewish businesses. One of the results was increased emigration, especially to South Africa and Palestine.

But Lithuanian independence was short lived. The Ribbentrop-Molotov agreement placed Lithuania in the Soviet sphere of influence and by October 1939 Lithuania became part of the Soviet Union. The events leading to the annihilation of the magnificient centuries old Litvak community and culture had now been set in motion.

In fact the educational system was one of the most important achievements of the Jewish national autonomy. The cost was initially borne by the state and three school systems flourished: the Zionist Hebrew language Tarbut schools; the socialist-Yiddisheit schools and the religious schools of the Yavneh network. In addition there were also traditional Cheder, Talmud Torah and Yeshivot (see above). Jewish students had been a significant part of the student body of the universities but the gradual introduction of the numerus clausus meant that by 1936 no Jews were admitted to learn medicine and the proportion of Jewish students in the other faculties fell sharply. Also associated with the educational system was YIVO - the Jewish Scientific Institute established in Vilna in 1925 to document Jewish life, history and culture.

Jews were also elected to the Lithuanian national assembly (Seimas), six in 1920, and seven in 1923. As minority rights were eroded, Jewish (and Polish) representation dropped. In 1926 a military coup d'etat led to the establishment of an authoritarian government under Antanas Smetona of the extremist nationalist Tautininkai. Agrarian reform, and the government assisted formation of cooperatives to control trade, affected especially Jewish traders. Most small Jewish shops were unable to compete with the Lithuanian cooperatives, which enjoyed great privileges especially in respect of taxation. The economic position of the Jewish population became increasingly precarious, especially in face of the anti-Semitic campaign of 'Verslininkai', an organisation of Lithuanian traders and workers, using the slogan 'Lithuania for Lithuanians' who led a campaign to boycott Jewish businesses. One of the results was increased emigration, especially to South Africa and Palestine.

But Lithuanian independence was short lived. The Ribbentrop-Molotov agreement placed Lithuania in the Soviet sphere of influence and by October 1939 Lithuania became part of the Soviet Union. The events leading to the annihilation of the magnificient centuries old Litvak community and culture had now been set in motion.

Jewish Ministers of the Lithuanian Cabinet

Soloveichik, Rachmilewitz and Rosenbaum

Soloveichik, Rachmilewitz and Rosenbaum

Lithuanian Territorial Claims after Independence

for Memel (brown), Vilna (green), Grodno and Bialystok (beige).

for Memel (brown), Vilna (green), Grodno and Bialystok (beige).

YIVO Conference in Vilna in 1929

Jewish School in Shadova-Šeduva

Smetona

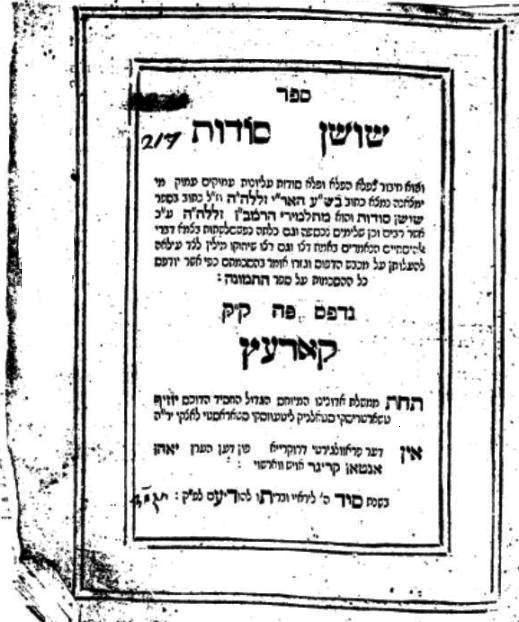

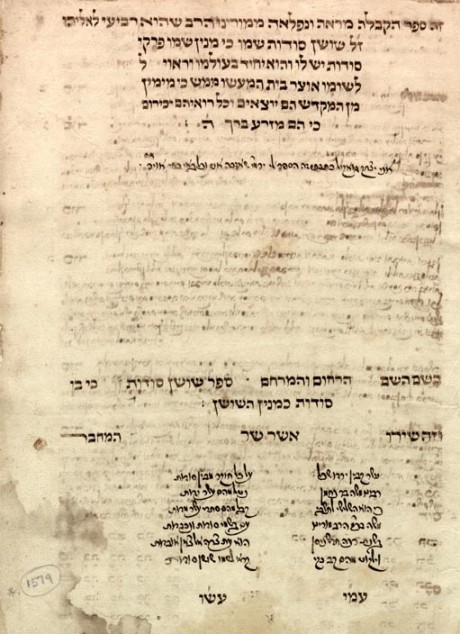

Rabbi Moshe ben Jacob of Kiev, known by his pseudonym Moshe ha-Goleh (the Exile), was born in Shadova - Šeduva in 1449. He was an important biblical exegete, Talmudic scholar, paytan, linguist, kabbalist and author. At a time where there were no important institutions for the Torah and Talmudic study in Poland and Russia, Moses ha-Goleh traveled to Constantinople where he studied under both Rabbinical and Karaite tutors, studying astronomy with the Karaite Eliyahu ben Moses Bashyazi of Adrianople (Adderet Eliyahu). Later Moshe settled in Kiev where he wrote a polemical work against Gan Eden, the book of precepts of the Karaite scholar Aharon ben Eliyahu. In 1482 the Tatars attacked Kiev, taking Moshe Ha-Goleh's children captive. In 1495 the Jews of Lithuania and the Ukraine were expelled (see above), and Moshe Ha-Goleh was forced to wander. At this time he wrote Shushan Sodot, Ozer ha-Shem and Sha’arei Zedek of which only the former is extant. Shushan Sodot is a kabalistic treatise with 656 entries discussing such subjects as cryptic writing, liturgy and commentary of the writings of the Rambam.

In 1506, while in Lida (now in Belarus), he was taken captive by the Tatars and taken to the Crimean city of Salaçıq (Bakhchysaray). Ransomed by the local Jewish community he settled in Caffa (Feodosiya) in the Crimea where he became the rabbi and head of the community. He united the members of the community who had come from disperse countries, compiling a prayer book known as Minhag Caffa, that was adopted by all the communities of the Crimea including the local Krymchaks. He also wrote Ozer Nehmad, a interpretation of the Pentateuch commentary of Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra. Moshe ha-Goleh died in Crimea around 1520.

Moshe HaGoleh of Shadova

Shoshan Sodot by Moshe HaGoleh

Edition published in 1788 in Korzec by Johann Anton Krieger

Edition published in 1788 in Korzec by Johann Anton Krieger

The Jews of Shadova - Šeduva

The earliest known Jewish settlement in Shadova - Šeduva dates to the fifteenth century, when the town is noted as the birthplace of Rabbi Moshe Ha-Goleh of Kiev (see box). With scant information relating to the Jewish community at this time we must leap forward to the offer of settlement for Jews in Shadova - Šeduva in the 18th century by the Lithuanian Deputy Chancellor Prince Kazimierz Czartoryski. By 1766 508 Jews were registered as paying the head-tax in the town. The Jews worked in trade, farming and crafts. At the end of the eighteenth century most of the 43 shops in Shadova - Šeduva were in Jewish hands. Jews also rented small plots for cultivation and would sell the best fruits and vegetables to merchants from Petersburg and Riga.

During the 1831 Polish insurrection against Czarist rule the Jews suffered at the hands of both the revolting Poles and Cossacks brought in by the Russian rulers to quell the insurgency. During this conflict cattle and horses were confiscated from the estates of the Polish nobles and assembled at the camp of the Russian General Tolstoy. On the 2nd July 1831 seven Jewish merchants from Shadova - Šeduva were accompanied to the camp to purchase the animals. On their way they were attacked by Polish rebels, robbed and lynched in the Pakalnišhkiai forest on the Neman River.

The earliest known Jewish settlement in Shadova - Šeduva dates to the fifteenth century, when the town is noted as the birthplace of Rabbi Moshe Ha-Goleh of Kiev (see box). With scant information relating to the Jewish community at this time we must leap forward to the offer of settlement for Jews in Shadova - Šeduva in the 18th century by the Lithuanian Deputy Chancellor Prince Kazimierz Czartoryski. By 1766 508 Jews were registered as paying the head-tax in the town. The Jews worked in trade, farming and crafts. At the end of the eighteenth century most of the 43 shops in Shadova - Šeduva were in Jewish hands. Jews also rented small plots for cultivation and would sell the best fruits and vegetables to merchants from Petersburg and Riga.

During the 1831 Polish insurrection against Czarist rule the Jews suffered at the hands of both the revolting Poles and Cossacks brought in by the Russian rulers to quell the insurgency. During this conflict cattle and horses were confiscated from the estates of the Polish nobles and assembled at the camp of the Russian General Tolstoy. On the 2nd July 1831 seven Jewish merchants from Shadova - Šeduva were accompanied to the camp to purchase the animals. On their way they were attacked by Polish rebels, robbed and lynched in the Pakalnišhkiai forest on the Neman River.

| Year | Population | Jews | % |

| 1766 | 508 | ||

| 1847 | 1211 | ||

| 1857 | 2357 | ||

| 1880 | 3783 | 2386 | 63 |

| 1897 | 4474 | 2513 | 56 |

| 1923 | 3186 | 916 | 29 |

| 1940 | 3736 | 800 | 21 |

| 1959 | 3253 | 4 | 0.12 |

| 1970 | 3184 | 1 | |

| 1989 | 4584 | ||

| 2009 | 3155 |

Population of Shadova-Šeduva

The early development of industrialisation and the growth of commercial agriculture in the Russian Empire was accompanied by a population boom in the mid-19th century, exhausting available land that transformed many Lithuanian peasants into migrant-labourers. The result was a famine between 1867 and 1870. Large numbers of Lithuanians emigrated. During the famine the Jews of Shadova - Šeduva received relief aid from the 'Va'ad

the Magid newspaper reported that the Shadova - Šeduva community was able itself to provide aid to poorer towns in Lithuania.

HaEzra' of Memel. However by 1871

Jewish community life concentrated around the prayer houses. A large wooden synagogue was built in 1866 in which a magnificent new Aron Kodesh was dedicated in 1895. Over time additional Shtiebels (small prayer houses) were added. The community was religious, the children receiving their education in a traditional 'Cheder'. In 1879 the community established a school with four classes. Rabbi Yosef Yehudah Leib Bloch founded a Yeshiva in Shadova - Šeduva for 50 'bachurim' (students). In 1910 he succeeded his father-in-law, Rabbi Eliezer Gordon, as Rosh Yeshiva of the famed Telshe Yeshiva. Rabbi Bloch created a new genre known as Shiurei Da’at, which were lectures on mussar and basic principles founded upon the unity of all aspects of the Torah and their root in the supernatural world. He was replaced in Shadova - Šeduva by Rabbi Aharon Bakesht. Other rabbis who served the community during this period were: Rabbi Gershon Kramer; Rabbi Eliezer-Simcha Rabinovitz (1861); Rabbi Simcha Horvitz (1871-1896); Rabbi Yehuda-Leib Riff (1886); Rabbi Noah Rabinovitz (1890-1901); Rabbi Avraham-Aaron Burshtein (19012); and Rabbi Yosef Kanovitz (1903).

Rabbi Yosef Yehudah Leib Bloch

Rabbi Aharon Bakesht

The main synagogue, consecrated in 1866, was built of wood. It was located in the middle of the town square, opposite the Russian Orthodox Church. They were both demolished and little information exists. In 1895 a beautifully carved ark was dedicated to provide a proper setting for what was considered the most ancient Torah Scrolls in Lithuania.

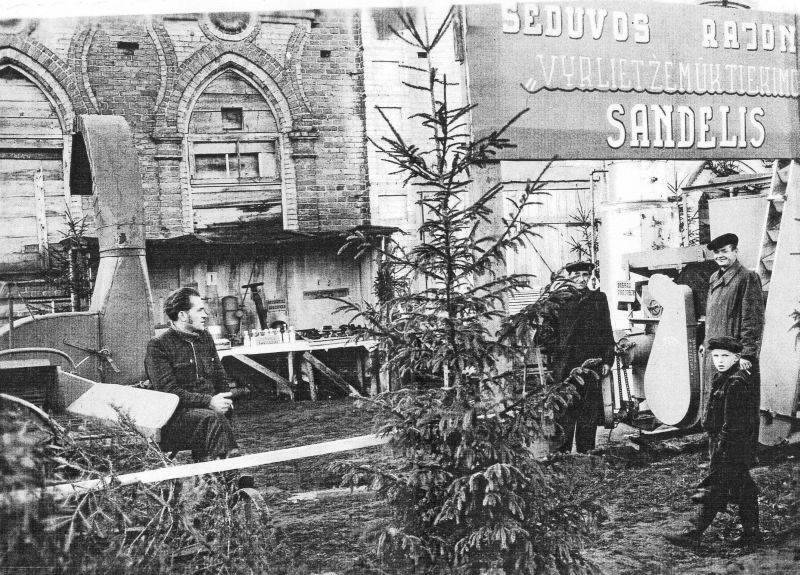

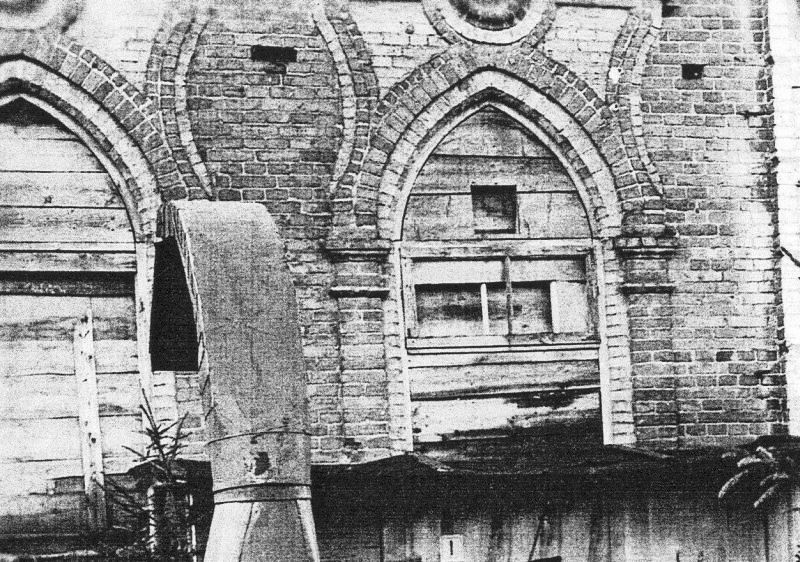

A second synagogue was built between 1900 and 1935 close to the square where the wooden synagogue was situated. It was constructed of red brick stone as seen in the photo taken after the war. In the 1960s the synagogue was destroyed and the debris used for paving paths through the park that was laid in the square where the the wooden synagogue had been built.

A second synagogue was built between 1900 and 1935 close to the square where the wooden synagogue was situated. It was constructed of red brick stone as seen in the photo taken after the war. In the 1960s the synagogue was destroyed and the debris used for paving paths through the park that was laid in the square where the the wooden synagogue had been built.

The Synagogues of Shadova - Šeduva

Is this the Wooden Synagogue of Shadova?

No surviving pictures of the Synagogue have been located. If you have one we will be pleased to post it here.

No surviving pictures of the Synagogue have been located. If you have one we will be pleased to post it here.

The Brick Synagogue before its Demolition in the 1960s

Site of Wooden Synagogue in the Town Square

Site of Brick Synagogue - Now a Market Square

Eliyahu's Chair used for the Brit Milah

In 1902 the aid society 'Somech Noflim' was founded with the aim of offering interest free loans. Other societies sent charity to the poor in Eretz Israel. Prior to WWI both Zionist organisations and the Bund were active in Shadova - Šeduva.

In 1871 fire destroyed many homes in the town. Some 150 homes were lost and 300 families were made destitute. The same occurred in 1884, leaving 200 families without shelter. Assistance was granted by donations from the Jewish community of Keidan and from Baron von Ropp, who owned the town and proved benevolent to the Jews. Fire would return to the town, destroying many buildings just before WWI.

After the anti-Semitic pogroms in 1881 the gates from Eastern Europe were opened and a steadily increasing trickle of Jewish emigrants left Shadova - Šeduva for South Africa, USA and even Palestine. The path from Lithuania involved a train journey through Europe, a voyage on a cargo boat to London, a stay in the Jews' Temporary Shelter in Leman Street, London, and then a long journey by sea to Cape Town or New York. Most of these immigrants were practical men and skilled artisans, mainly tailors, shoemakers and carpenters although there were also builders, clerks, butchers, caterers, watchmakers, engineers, bakers, tobacconists, barbers, tinsmiths, brassfounders, harnessmakers, waterproof makers, locksmiths, glaziers, printers, portmanteau makers, brush makers, mattress makers, soap makers, and photographers.

In 1847, the Jewish population of Shadova - Šeduva was 1211; in 1897, it was 2695, 61 % of the general population. During WWI the Jews, seen as potentially dangerous to Czarist rule, were expelled to the Russian interior, only 916 returning by after the war, now only 28% of the general population.

In 1871 fire destroyed many homes in the town. Some 150 homes were lost and 300 families were made destitute. The same occurred in 1884, leaving 200 families without shelter. Assistance was granted by donations from the Jewish community of Keidan and from Baron von Ropp, who owned the town and proved benevolent to the Jews. Fire would return to the town, destroying many buildings just before WWI.

After the anti-Semitic pogroms in 1881 the gates from Eastern Europe were opened and a steadily increasing trickle of Jewish emigrants left Shadova - Šeduva for South Africa, USA and even Palestine. The path from Lithuania involved a train journey through Europe, a voyage on a cargo boat to London, a stay in the Jews' Temporary Shelter in Leman Street, London, and then a long journey by sea to Cape Town or New York. Most of these immigrants were practical men and skilled artisans, mainly tailors, shoemakers and carpenters although there were also builders, clerks, butchers, caterers, watchmakers, engineers, bakers, tobacconists, barbers, tinsmiths, brassfounders, harnessmakers, waterproof makers, locksmiths, glaziers, printers, portmanteau makers, brush makers, mattress makers, soap makers, and photographers.

In 1847, the Jewish population of Shadova - Šeduva was 1211; in 1897, it was 2695, 61 % of the general population. During WWI the Jews, seen as potentially dangerous to Czarist rule, were expelled to the Russian interior, only 916 returning by after the war, now only 28% of the general population.

| Retail Trade | Total Owners | Jews |

| Grocer | 1 | 1 |

| Flax Comber | 1 | 1 |

| Butcher & Cattle Trader | 6 | 6 |

| Restaurant & Public House | 1 | 0 |

| Food Products | 7 | 7 |

| Liquor | 1 | 1 |

| Clothes, Fur & Textiles | 5 | 5 |

| Leather & Shoes | 2 | 2 |

| Household Goods | 2 | 2 |

| Pharmacy & Cosmetics | 2 | 0 |

| Watchmaker & Jewelry | 1 | 1 |

| Radios, Sewing Machines & Electronics | 2 | 2 |

| Fuel | 2 | 2 |

| Paper, Books & Stationary | 1 | 0 |

| Industry | Total Owners | Jews |

| Metal & Power | 1 | 1 |

| Textile: Wool, Flax & Weaving | 3 | 2 |

| Wood: Carpentry, Cabinet Making | 1 | 1 |

| Food: Milling, Bakeries, Liqour, Confectionry | 10 | 6 |

| Clothes, Shoes, Fur & Milners | 3 | 2 |

| Other Trades: Barber, Pig Bristle Brushes | 2 | 1 |

The Market Place in Shadova - Šeduva

Independent Lithuania

The families who returned to Shadova - Šeduva after the war set about reestablishing their businesses and community. The new independent government of Lithuania initially gave control of communal affairs to a self governing council. The first council, operating from 1920 to 1925, comprised of two members of Zairei Zion, one from Mizrachi and eight unaffiliated members. In the elections to the municipal council in 1931 two Jews, Leizar Melamed and Berel Faim, were elected to a council of nine.

The families who returned to Shadova - Šeduva after the war set about reestablishing their businesses and community. The new independent government of Lithuania initially gave control of communal affairs to a self governing council. The first council, operating from 1920 to 1925, comprised of two members of Zairei Zion, one from Mizrachi and eight unaffiliated members. In the elections to the municipal council in 1931 two Jews, Leizar Melamed and Berel Faim, were elected to a council of nine.

A survey of the work sector conducted by the Lithuanian government in 1931 records 36 shops in Shadova - Šeduva, of which 31 were in Jewish hands, as were 13 of the 20 small industries (see table). The Jews were employed as traders, shop keepers, artisans and in small industry.

In 1925, for example, the community included a doctor, dentist, while in 1937 there were 8 shoe makers, 7 tailors, 6 butchers, 3 barbers, 2 hat makers, 2 tin smiths, a butcher, glazier, bookbinder, framer, painter, photographer and a tiler. The Artisans Association of Shadova - Šeduva was chaired in 1938 by Y. Kolecktor, with Shimon Segal as secretary and Lipa Pamuz as treasurer. There were two flour mills owned by Jews and the Cohen family had a dye-works and a weaving factory.

The Jewish Peoples Bank (Folksbank) played an important part in the economy with 266 members in 1927 and 216 in 1929.

The Jewish community developed an active social, educational and political life. The town had a yeshiva, two cheders, a Tarbut School, whose headmaster was Fisch, and a library with books in Hebrew, Yiddish, Russian and German. The better students traveled to Kovno, Shavel and Ponavezh to study at the Hebrew language Gymnasia and the higher Yeshivot. The majority of the community were involved in Zionist activities, the youth active in Hashomer Hatzair, the largest movement with 76 members in 1932; Maccabi and HeChalutz, the latter opering an urban Kibbutz in Shadova - Šeduva in 1934 called 'Kibbutz HaCovesh'. The religious youth belonged to Tiferet Bachurim and Bet Ya'acov. Religious life continued from the previous period in the synagogues, the Bet Midrash and Stiebelach. The Rabbis during this period were Rabbi Aaron Bakesht (1915); Rabbi Benzion Notlevitz (1922); and the last rabbi, Rabbi Mordechai-David Henkin who would be murdered along with the entire community during the Shoah.

Trades and Economy of the Jewish Community

Jewish Life in Shadova Before the Holocaust

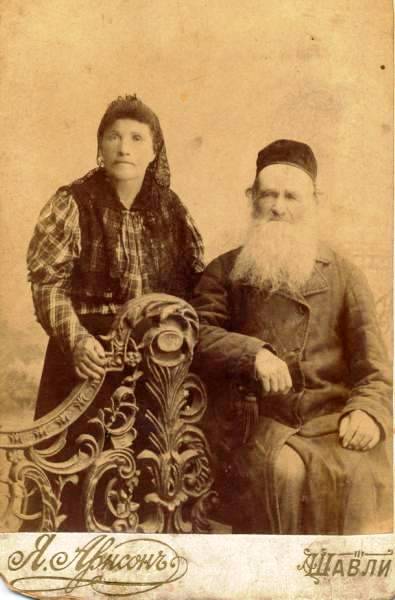

The Stein Family

Wedding in Johannesburg of Ledermans from Shadova

Goldbergs on visit to Shavel

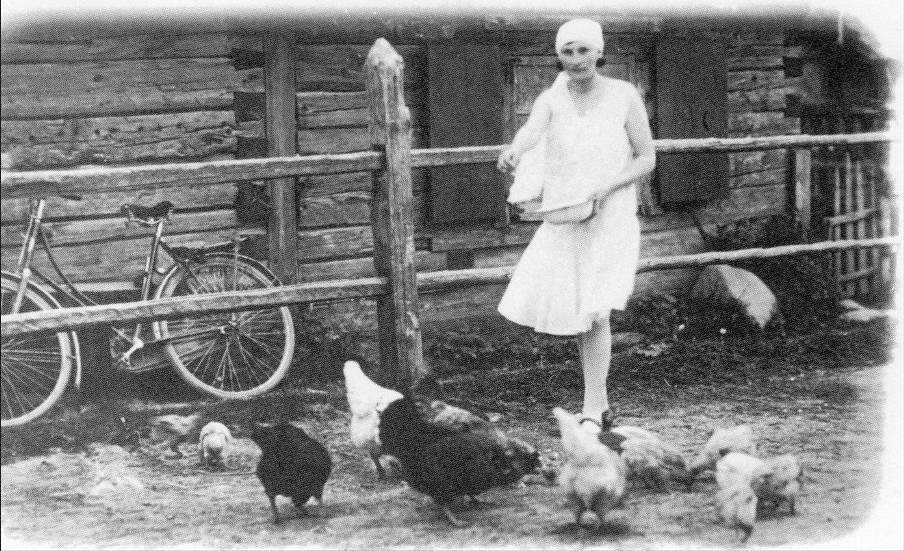

Feeding Chickens in a Shadova Garden

HaShomer HaZair

Aliyah party for two members in 1930

Aliyah party for two members in 1930

Hachshara of HaShomer HaZair in Shadova

Meetings of the Shadova branch of HeChalutz and training at the Hachshara farm named Kibbutz HaCovesh in the 1930s.

Zionist youth gathers for in Shadova for meetings, outings, activism, trips and play.

Sports Day of the Maccabi Association of Ponovezh, Radviliskis and Shadova in 1926.

Party for H. Margalit on the day of here Aliya from Shadova to Eretz Israel - 1929.

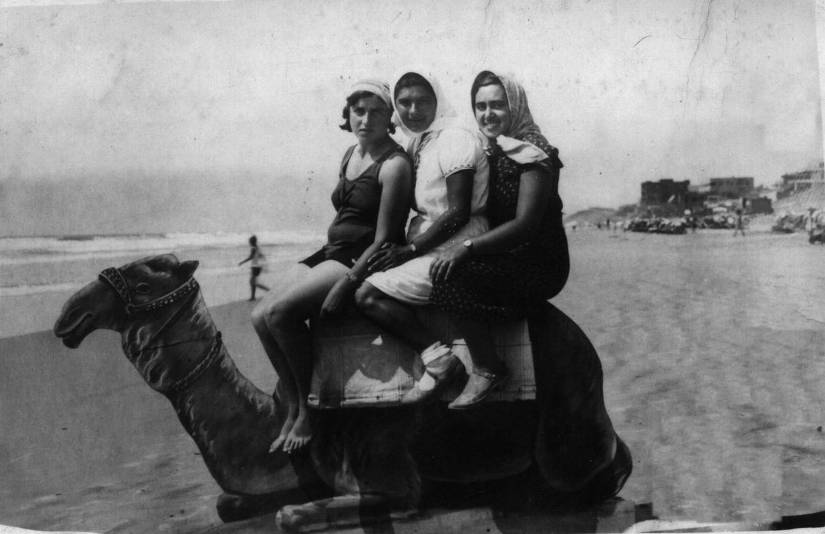

Zionist youth from Shadova on a fake camel on the beach in Tel Aviv after their Aliya.

The Road to the Jewish Cemetery of Shadova-Šeduva and Views of the Cemetery Today - The Last Trace of Extinct Jewish Life

Eroded Gravestones in the Jewish Cemetery of Shadova-Šeduva. A Final Testimony to a Community

A list of the gravestones from the cemetery can be found here.

A list of the gravestones from the cemetery can be found here.

Copyright © 2009 Jon Seligman. All Rights Reserved.

The Jewish Homes of Shadova - Šeduva

Yehuda Grodnik, Baruch Gofer and Alter Kaplan, former residents of the shtetl, collated a house by house list of the Jewish residents of Shadova - Šeduva prior to the holocaust. This list has been published before and is supplemented here.

Yehuda Grodnik, Baruch Gofer and Alter Kaplan, former residents of the shtetl, collated a house by house list of the Jewish residents of Shadova - Šeduva prior to the holocaust. This list has been published before and is supplemented here.

| Zionist Congress | Year | General Zionists | Zairei Zion | Socialist Zionists | Revisionists | Medinatiim | Mizrachi | Total |

| 16 | 1929 | 4 | 4 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 25 | |

| 17 | 1931 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 14 | 6 | 35 | |

| 18 | 1933 | 10 | 96 | 3 | 25 | 135 | ||

| 19 | 1935 | 60 | 132 | 16 | 47 | 255 | ||

| 21 | 1939 | 5 | 44 | 19 | 68 | |||

Shadova - Šeduva Voting for the Zionist Congresses

The Jewish community developed an active social, educational and political life. The town had a yeshiva, two cheders, a Tarbut School, whose headmaster was Fisch, and a library with books in Hebrew, Yiddish, Russian and German. The better students traveled to Kovno, Shavel and Ponavezh to study at the Hebrew language Gymnasia and the higher Yeshivot. The majority of the community were involved in Zionist activities, the youth active in Hashomer Hatzair, the largest movement with 76 members in 1932; Maccabi and HeChalutz, the latter opering an urban Kibbutz in Shadova - Šeduva in 1934 called 'Kibbutz HaCovesh'. There was an active secular cultural that centered on literature and theatre. In 1935 a public 'trial' was held for Sholem Asch's controversial play - 'Got fon Nekoma' (God of Vengence). The religious youth belonged to Tiferet Bachurim and Bet Ya'acov. Religious life continued from the previous period in the synagogues, the Bet Midrash and Stiebelach. The Rabbis during this period were Rabbi Aaron Bakesht (1915); Rabbi Benzion Notlevitz (1922); and the last rabbi, Rabbi Mordechai-David Henkin who would be murdered along with the entire community during the Shoah.

The depression of the thirties led to a rise in anti-Semitism, resulting in a blood libel in Shadova - Šeduva in 1931 and a boycott of Jewish businesses following heavy propaganda by the Lithuanian Merchants Association - 'Verslininkai'. The situation was influenced by the growth of anti-semitism that accompanied the election of the Smetona authoritarian government in Lithuania and the occupation of Memel by the Nazis in 1939. Many Jews now relied on financial support from relatives in South Africa and America. With continued emigration the Jewish population of Shadova - Šeduva in 1939 consisted of only 200 families (about 800 souls), now only 21 % of the total. With the Soviet occupation in 1940 all the private shops and businesses were nationalised. The Jews were especially affected as they still formed the backbone of the local economy. At the same time the Zionist parties and youth movements were made illegal and the community organisations and schools closed.

Operation Barberossa commenced on the 22nd June 1941. Three days later the Wehrmacht occupied Shadova - Šeduva and were received with flowers by the local Lithuanians. Within less than two months the centuries old Jewish community of Shadova - Šeduva had ceased to exist.

The depression of the thirties led to a rise in anti-Semitism, resulting in a blood libel in Shadova - Šeduva in 1931 and a boycott of Jewish businesses following heavy propaganda by the Lithuanian Merchants Association - 'Verslininkai'. The situation was influenced by the growth of anti-semitism that accompanied the election of the Smetona authoritarian government in Lithuania and the occupation of Memel by the Nazis in 1939. Many Jews now relied on financial support from relatives in South Africa and America. With continued emigration the Jewish population of Shadova - Šeduva in 1939 consisted of only 200 families (about 800 souls), now only 21 % of the total. With the Soviet occupation in 1940 all the private shops and businesses were nationalised. The Jews were especially affected as they still formed the backbone of the local economy. At the same time the Zionist parties and youth movements were made illegal and the community organisations and schools closed.

Operation Barberossa commenced on the 22nd June 1941. Three days later the Wehrmacht occupied Shadova - Šeduva and were received with flowers by the local Lithuanians. Within less than two months the centuries old Jewish community of Shadova - Šeduva had ceased to exist.

HaShomer HaZair in Shadova

The Shtetl's largest youth movement

The Shtetl's largest youth movement

All That Survives - The Jewish Cemetery in Shadova - Šeduva Today

Remains of a now bricked up Synagogue in Shadova