History of Kraslava - Two

55°54'N, 27°10'E

Russians, Poles, Latvians & Soviets - The History of Kraslava

From the Nineteenth Century till Today

From the Nineteenth Century till Today

Latgale Under Imperial Russian Rule

With the first partition of Poland and the consequent annexation of Inflanty (Polish Livonia) to Russia in 1772, Latgale was initially included in the Pskov Gubernia. By 1776 the Dvinsk region had been joined with the Vitebsk, Polotsk and Mogilev regions to form the Belarussian General Province with a capital in Vitebsk. and from 1802 in the Vitebsk Gubernia. Unlike the other Baltic provinces that maintained a degree of automony, Vitebsk became an integral part of the Russian empire, lagging economically, politically and intellectually behind the its Baltic neighbours. Still, even with the regime change the Polonised Teutonic szlachta continued to dominate their estates, villages and towns.

With the first partition of Poland and the consequent annexation of Inflanty (Polish Livonia) to Russia in 1772, Latgale was initially included in the Pskov Gubernia. By 1776 the Dvinsk region had been joined with the Vitebsk, Polotsk and Mogilev regions to form the Belarussian General Province with a capital in Vitebsk. and from 1802 in the Vitebsk Gubernia. Unlike the other Baltic provinces that maintained a degree of automony, Vitebsk became an integral part of the Russian empire, lagging economically, politically and intellectually behind the its Baltic neighbours. Still, even with the regime change the Polonised Teutonic szlachta continued to dominate their estates, villages and towns.

In spite of the political and cultural pressures Latgale retained its identity, language, Catholic faith and other cultural features. Important to the preservation of the culture was the singing of popular ancient folk songs that preserved the language, culture and customs. This national reawakening (Atmoda) developed initially among the Latgalian intelligentsia in St. Petersburg and then penetrated Latgale through the appearance from 1904 of Latgalian newspapers and books and the establishment of Latgalian schools, economic cooperatives, theater groups and other organisations. Soon the revolutionary actions of 1905, that affected many regions of the Russian Empire, were strongly felt in Latgale. The resulting unrest was expressed through petitions, strikes and the burning of estates; actions heavily repressed by the Czarist authorities.

Pskov Gubernia

Vitebsk Gubernia

From the 1830s the region was heavily influenced by the russification policy of the Czarist government. The impact of this was especially evident in the continued serfdom of the peasants of Latgale till 1861, a policy already abolished in Livonia and Courland in 1818. This became the main cause for the social and economic backwardness of the Latgalian peasants, a situation exacerbated by the restrictions of the Russian village system that continued even after their liberation from serfdom. Russification intensified after the failed Polish insurrections of 1830-1 and 1863. Following the insurrection the Russians curbed the power of the Polish nobility and the Catholic church. Furthermore, Russian peasants were encouraged to settle in Latgale, the Orthodox faith was officially endorsed and the Russian language was imposed through the ban on the use of the Latin alphabet. The Latgalians were repressed in their own country. They could not own land, start their own schools or serve in any official capacity.

Latgale Costume

Emilia Plater

Leader of 1830 Uprising

Leader of 1830 Uprising

Kraslava - from the end of the 18th till the mid 19th centuries

Together with the rest of the region Kraslava too came under the dominance of Czarist rule in 1772. The Plater's desire to transform Kraslava into a regional centre and a Catholic Bishopric were no longer aspirations under their own control, but now relied on the inclinations of the new authorities. After August Eronim Hyacinth Plater (1750 - 1803) inherited Kraslava in 1778, he too became an important figure in the life of the Latgale, participating as a representative of Pskov Gubernia at the crowning of Czar Pavel I in St. Peterburg in 1797. He was replaced by Count Adam Plater (1790 - 1862) who beyond being an active politician and agrarian reformer, was also a published scholar of archeology, history and science.

Together with the rest of the region Kraslava too came under the dominance of Czarist rule in 1772. The Plater's desire to transform Kraslava into a regional centre and a Catholic Bishopric were no longer aspirations under their own control, but now relied on the inclinations of the new authorities. After August Eronim Hyacinth Plater (1750 - 1803) inherited Kraslava in 1778, he too became an important figure in the life of the Latgale, participating as a representative of Pskov Gubernia at the crowning of Czar Pavel I in St. Peterburg in 1797. He was replaced by Count Adam Plater (1790 - 1862) who beyond being an active politician and agrarian reformer, was also a published scholar of archeology, history and science.

Alexander Nevsky Orthodox Church

Iconostas

Alexander Nevsky

Alexander Nevsky

By 1852 Kraslava had 3030 inhabitants; 389 houses - mostly wooden but a few of stone; and a workshop for making Dutch tiles. Though the Catholic congregation, led by the Platers, remained dominant there was a strong Russian Orthodox community. In 1840 a Russian Orthodox church was sanctifyed in honour of St. George. Count Adam Plater tithed twelve stone shops in the centre of the town for the church’s requirements. Soon this church did not meet the requirements of the large orthodox community and a new structure dedicated to the Virgin in 1859. Following the Polish Uprising of 1863 the Platers provided land in the eastern part of Kraslava.to billit the Czarist troops, under the command of M. Muravjovs, the governor general of the Vitebsk Gubernia. The Russian Imperial Army established barracks, warehouses and an infirmary for 4000 soldiers. Furthermore the Platers agreed to give part of the former catholic monastery to the army to consecrate an Orthodox church named for Alexander Nevsky.

The Russian Old-Believers built their meeting house on the river bank in Ratuzha street in 1850. Nine years later a local merchant funded the construction of a new building dedicated to the Mother-God (Theotokos)which served the community till burning in 2002.

The Russian Old-Believers built their meeting house on the river bank in Ratuzha street in 1850. Nine years later a local merchant funded the construction of a new building dedicated to the Mother-God (Theotokos)which served the community till burning in 2002.

Old & New Church of the Mother God of the Old Believers

Schools

After departing Kraslava at the end of the eighteenth century the Jesuits established their central educational institution in the huge fortress in Dyneburg (Dvinsk). With increased military requirements for space within the fortress the Jesuits were forced to seek new premises. In 1811 they returned to Kraslava, establishing a new school. By 1814 the Jesuits transferred to Izvalta and the school remained the care of the Lazarists (Vincentian Fathers). Schooling was in Polish and Latin until 1825 when the Czarist government required the instruction to be conducted in Russian.

A girls boarding school opened in Kraslava in 1826, joined later by a school for the children of the peasants and a girl's orphanage. In addition Count Adam Plater founded a gymnasium in Kraslava as the district school for the children of landowners. However, the provincial government in Vitebsk was not happy with the intervention of the Platers and decided to move the district school to Rezekne in 1854.

After departing Kraslava at the end of the eighteenth century the Jesuits established their central educational institution in the huge fortress in Dyneburg (Dvinsk). With increased military requirements for space within the fortress the Jesuits were forced to seek new premises. In 1811 they returned to Kraslava, establishing a new school. By 1814 the Jesuits transferred to Izvalta and the school remained the care of the Lazarists (Vincentian Fathers). Schooling was in Polish and Latin until 1825 when the Czarist government required the instruction to be conducted in Russian.

A girls boarding school opened in Kraslava in 1826, joined later by a school for the children of the peasants and a girl's orphanage. In addition Count Adam Plater founded a gymnasium in Kraslava as the district school for the children of landowners. However, the provincial government in Vitebsk was not happy with the intervention of the Platers and decided to move the district school to Rezekne in 1854.

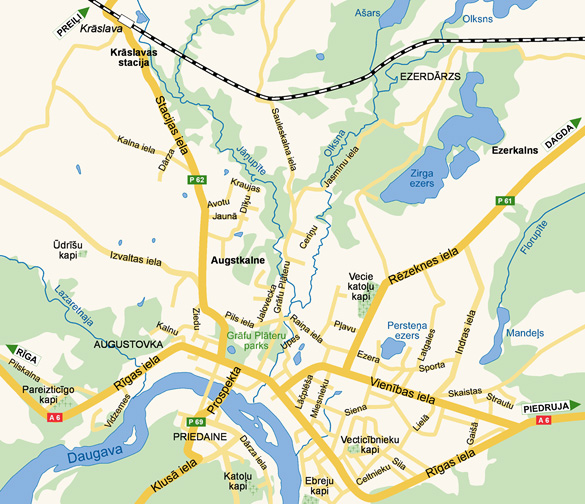

1

2

3

4

6

9

8

7

5

10

1 - Plater Estate

2 - Market Square

3 - St.Ludwig

Catholic Church

4 - Main Synagogue

5 - Jewish Cemetery

6 - Catholic Cemetery

7 - Plater Library

8 - Train Station

9 - Adamova Hill

10 - Orthodox Church

11 - Big Prayer House

12 - Death Pits &

Memorial Site

2 - Market Square

3 - St.Ludwig

Catholic Church

4 - Main Synagogue

5 - Jewish Cemetery

6 - Catholic Cemetery

7 - Plater Library

8 - Train Station

9 - Adamova Hill

10 - Orthodox Church

11 - Big Prayer House

12 - Death Pits &

Memorial Site

KRASLAVA

Modernity reaches Kraslava

A section of the St. Petersburg - Warsaw railway reached Dvinsk at the end of the 1860, and a side line was opened to Polotsk in 1866 passing through Kraslava. The building of the railroad and especially emancipation of the serfs that resulted from the social reforms of 1861 led to the growth of population and the development of trade and industry in Kraslava. By 1867 there were 4017 people in the Kraslava with 525 houses, 111 commercial properties, 13 taverns, leather factories, two windmills, a brewery and a spirit production industry.

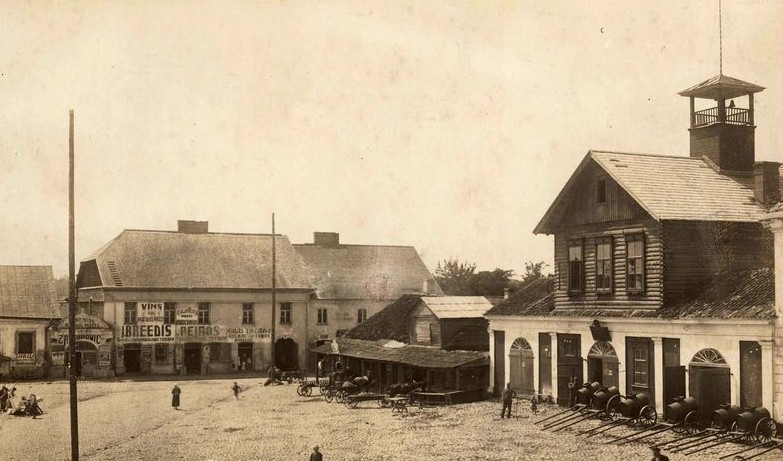

After fires devastated Kraslava in 1882 it was decided to organise a voluntary fire-brigade under the leadership of influential citizens of Kraslava. Kurkovsky, the first fire chief bought two big pumps, water barrels and the necessary equipment. A stone building was assigned by Count Gustav Plater in the centre of Kraslava, and 120 volunteers were recruited. After the failure to cope with the catastrophic fire of 1893, during which much of the town was lost the fire-brigade purchased a mobile fire-engine and the fire station was enlarged. As was customary the fire brigade organised a brass band that performed at the concerts and dancing parties in the town.

A section of the St. Petersburg - Warsaw railway reached Dvinsk at the end of the 1860, and a side line was opened to Polotsk in 1866 passing through Kraslava. The building of the railroad and especially emancipation of the serfs that resulted from the social reforms of 1861 led to the growth of population and the development of trade and industry in Kraslava. By 1867 there were 4017 people in the Kraslava with 525 houses, 111 commercial properties, 13 taverns, leather factories, two windmills, a brewery and a spirit production industry.

After fires devastated Kraslava in 1882 it was decided to organise a voluntary fire-brigade under the leadership of influential citizens of Kraslava. Kurkovsky, the first fire chief bought two big pumps, water barrels and the necessary equipment. A stone building was assigned by Count Gustav Plater in the centre of Kraslava, and 120 volunteers were recruited. After the failure to cope with the catastrophic fire of 1893, during which much of the town was lost the fire-brigade purchased a mobile fire-engine and the fire station was enlarged. As was customary the fire brigade organised a brass band that performed at the concerts and dancing parties in the town.

Kraslava Burns

The Fire Station

The population grew rapidly. In 1897 Kraslava had 7825 people with several schools, a hospital, a bristle plant owned by the Churin family and a tannery. Others found employment on the Plater estate, on the railroad, floating timber along the Dvina river, in workshops, in flax manufacture and trading. With the development of industry came the conflict of capital and labour that so characterised the period. Typically working conditions were poor, salaries low and hours long. The first strike occurred in the Churin Bristle Factory in 1898 when workers, the majority of them Jews, protested the deduction of a ruble a week from their wage. With the radicalisation of the workers a branch of the Russian Social-Democratic party and the Bund organised in 1900. The workers gave support to the revolution of 1905, closing the factories for five days in January 1905. After unrest, meetings, marches and demonstrations a dragoon regiment arrived in Kraslava and surrounded the Bristle Plant with its 180 workers on February 16, 1906. Sixty-seven workers were badly beaten and taken to prison in Dvinsk. The government fined the town 30000 rubles for the troubles, causing economic collapse and hunger. Eventually the Czarist Minister of Internal affairs recalled the militia and returned the fine.

Electricity came to Kraslava in 1912, providing light initially to the Platers’ palace, the castle, army barracks, the churches, the chemists and the rest of the town. 10500 people lived in Kraslava by 1914, ruled by the last Marya and Gustav Plater, the last of their line resident in their estate. The Czarist government had offered to purchase Kraslava from the Platers for 2 million gold rubles in 1910, an offer that was rejected. With the outbreak of WWI the Platers were forced to leave and the contents of the palace and other family heirlooms were sent to St. Petersburg in 1916, only to be lost in the Russian revolution.

From the mid-19th century a total of eight schools operated in Kraslava. The Polish language boys school sprang from the school that opened in 1751. It taught 162 pupils in 1919 and closed in 1947. A folk school for the poorer population was founded in 1864 with Russian language teaching of religion and elementary education. A Jewish elementary school operated in Kraslava in two rooms of a private house until a donation from the Churin, the owner of the bristle factory, provided funds to construct a school building in Skolas Street. The Soviets closed the Jewish school in 1940.

A small hospital with ten beds continued to provide health care. In 1871 the director was Anton Fedorovich from Vitebsk and a graduate of Tartu University. After coming to Kraslava as a district doctor he later moved on to Dvinsk. A medical health resort functioned between 1870 to 1900 using the sulfurous mineral waters for which Kraslava was well known. The waters were bottled for sale in Russia and were used for the treatment of weakness and anemia.

From the mid-19th century a total of eight schools operated in Kraslava. The Polish language boys school sprang from the school that opened in 1751. It taught 162 pupils in 1919 and closed in 1947. A folk school for the poorer population was founded in 1864 with Russian language teaching of religion and elementary education. A Jewish elementary school operated in Kraslava in two rooms of a private house until a donation from the Churin, the owner of the bristle factory, provided funds to construct a school building in Skolas Street. The Soviets closed the Jewish school in 1940.

A small hospital with ten beds continued to provide health care. In 1871 the director was Anton Fedorovich from Vitebsk and a graduate of Tartu University. After coming to Kraslava as a district doctor he later moved on to Dvinsk. A medical health resort functioned between 1870 to 1900 using the sulfurous mineral waters for which Kraslava was well known. The waters were bottled for sale in Russia and were used for the treatment of weakness and anemia.

World War I and Revolution come to Kraslava

Kraslava found itself in the vortex of the events of World War I. Latgale was an area of heavy fighting between Russian, German, Polish and Latvian forces. Thirty-eight different military units passed through the town during the battles. As the front line approached the Russians evacuated the town on the 1st. September 1915, taking with them factory machinery, the Russian school and the church icons.

During the war two bridges were built across the river, a wooden bridge opposite the Jewish graveyard and the barge bridge at the site of former river ferry. Being a strategic position trenches were excavated along the Dvina. Russian forces established a command post in the town under General Oranovski and the Kraslava troops were inspected by Prince Boris Vladimirovich and Prince Lichtenbergsky in June 1916. The Russian emplacements were bombed from the air by the Germans in September 1916 causing damage to the Post Office and nearby buildings.

Kraslava found itself in the vortex of the events of World War I. Latgale was an area of heavy fighting between Russian, German, Polish and Latvian forces. Thirty-eight different military units passed through the town during the battles. As the front line approached the Russians evacuated the town on the 1st. September 1915, taking with them factory machinery, the Russian school and the church icons.

During the war two bridges were built across the river, a wooden bridge opposite the Jewish graveyard and the barge bridge at the site of former river ferry. Being a strategic position trenches were excavated along the Dvina. Russian forces established a command post in the town under General Oranovski and the Kraslava troops were inspected by Prince Boris Vladimirovich and Prince Lichtenbergsky in June 1916. The Russian emplacements were bombed from the air by the Germans in September 1916 causing damage to the Post Office and nearby buildings.

Nearby Dvinsk was occupied by German troops on February 18th, 1918 and German planes flew over Kraslava on February 20th prior to the arrival of a German contingent who occupied the town. Strict military control was imposed and refugees who had found shelter in the town were expelled. German occupation continued till December 9th, 1918, when the German troops retreated, to be replaced by the Bolsheviks. The Red Guards opened a revolutionary Soviet in the cinema building in December 1918. This was a period of conflict and struggle against anti-revolutionary forces. Members of szlachta families and many Poles were arrested, especially with the imminent approach of Polish forces in autumn 1919. During the Battle of Daugavpils from September 1919 to January 1920, the Polish Third Polish Legion Infantry Division, commanded by Edward Rydz-Smigly, drove the Bolsheviks from Kraslava after heavy battles near

Dvina River Ferry

Bridge on the Dvina River

By February 1917 revolution had engulfed the area. A local committee for safety and police were founded for the inhabitants' protection on March 12, 1917. Refugees, who were moving throughout the area, attacked the Czarist representative who promptly left Kraslava for St. Petersburg. Later the committee decided to arrest Count Gustav Plater, forcing him to leave Kraslava. He later returned during the German occupation, only to leave permanently with the arrival of the Bolsheviks. After Gustav Plater’s death in Riga in 1923, Marya Plater sold the remaining land and moved to Spain.

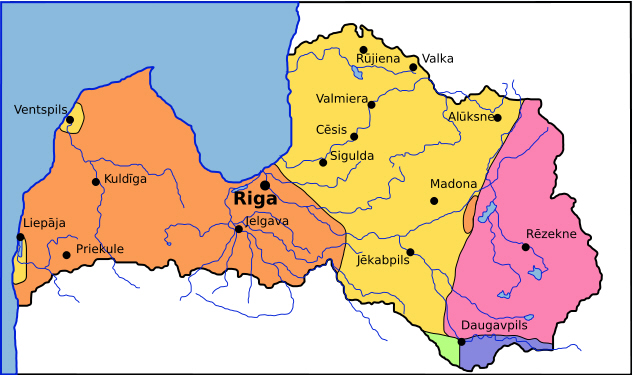

Polish-Soviet War - Army Movements

Latvia at the end of WWI

Germans - orange; Latvians - yellow; Bolsheviks - pink; Poles - blue; Lithuanians - green

Germans - orange; Latvians - yellow; Bolsheviks - pink; Poles - blue; Lithuanians - green

Edward

Rydz-Smigly

Rydz-Smigly

the town that caused further damage to houses and the destruction of the wooden bridge across the Dvina. Polish intention was to place the mainly Polish towns of southern Latgale, including Kraslava, under their control. However, one of the results of WWI was the formation of a new Latvian Republic. Negotiations between the new Latvian government and the Polish war representative took place in Riga in December 1919 during which agreement was sort for the removal of the Red Army from Latgale. By January 1920 control over Latgale was achieved and newly formed Latvian state took control of the region.

The Battle of Daugavpils

The actions of both the German and the Russian forces resulted in mass expulsions of civilians from their homes in Latvia and Latgale. The cynical use of anti-Semitism by the Czarist forces against Jewish citizens and their forced deportation to the Russian interior, some in rail cars bearing the sign 'shpioni' (spies), created an acute refugee problem. The Germans in turn used forced labour as a basic principle of their policy for civilian administration and moved people around for their own military requirements.

Boris Vladimirovich

Kraslava after Latvian Independence

The pre-war population of over 10000 was devastated through deporatation, population transfer to the Russia interior and emigration to the New World. Only 3564 people returned to the town - 1446 of whom were Jews; 794 Belarussians; 500 Poles, 343 Russians and only 372 Latvians. Of the 806 houses 121 had been destroyed during the fighting.

The new town council immediately embarked on reconstruction, under the leadership of the Polish elite and the first mayor - Lucian Gzhibovsky. Cultural renaissance, known as Atmoda (Latvian national awakening), led to the foundation of a Latvian language gymnasium in the

The pre-war population of over 10000 was devastated through deporatation, population transfer to the Russia interior and emigration to the New World. Only 3564 people returned to the town - 1446 of whom were Jews; 794 Belarussians; 500 Poles, 343 Russians and only 372 Latvians. Of the 806 houses 121 had been destroyed during the fighting.

The new town council immediately embarked on reconstruction, under the leadership of the Polish elite and the first mayor - Lucian Gzhibovsky. Cultural renaissance, known as Atmoda (Latvian national awakening), led to the foundation of a Latvian language gymnasium in the

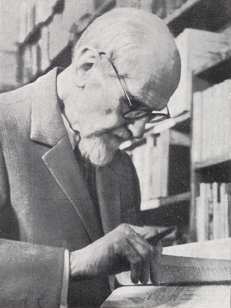

Moisei Rabinovich

Janis Cakste

the savings-bank, the Jewish savings bank, the Dairy Association, The Red Cross etc.

In April 1923 Janis Cakste, the President of Latvia, awarded Kraslava the status of a town. In 1927 the new mayor, the pharmacist Moisei Rabinovich (1883 - 1941), provided the town with its coat of arms, a silver boat with five oars in the blue background, symbolising the inhabitants of the town - the Latvians, the Poles, the Jews, the Russians and the Belarussians.

In April 1923 Janis Cakste, the President of Latvia, awarded Kraslava the status of a town. In 1927 the new mayor, the pharmacist Moisei Rabinovich (1883 - 1941), provided the town with its coat of arms, a silver boat with five oars in the blue background, symbolising the inhabitants of the town - the Latvians, the Poles, the Jews, the Russians and the Belarussians.

former palace of the Platers. Elementary schools opened for the Latvian, Polish, Russian and Jewish children of Kraslava; the medical services were reestablished; the electricity supply renewed and a series of commercial and social associations established - the Kraslava Consumers Society, the Kraslava Agricultural Society, Latvian Society,

Kraslava

Coat of Arms

Coat of Arms

Following the land reform policy of independent Latvia the Plater estate was taken by the state for public use. In 1921 the Ministry of Education rented the palace for the purpose of opening an educational institution and a year later the Kraslava Gymnasium opened there. Latin and German language studies were central to the studies and in the twenties Raul Shnore, a historian and archaeologist, worked at the school and led archaeological excavations in the district for the Latvian Inspectorate for Heritage Protection. A literary circle also operated from the gymnasium, concentrating on the teaching of Latgalian folk culture. Indeed the introduction of Latvian language instruction was an important step in the imposition of Latvian cultural hegemony.

Medical facilities expanded after WWI. Fifteen beds were initially available in the hospital, later expanding to twenty. The doctors were Anton Kosminsky, Georg Serikov, Ernst Reinson, Leiba Mirvis, Nikolay Bokum and Janis Zerbuk. In addition a sanatorium opened in 1930 with 20 beds for the treatment of tuberculosis. The pharmacy was operated by the chemist by Samuel Shmuda, who would die during the murder of Kraslava's Jews in 1941. Under German occupation Janis Zerbuk continued to manage the hospital and later a new hospital with 60 beds was organised by Nikolay Bokum. Having collaborated with the Nazis, both these doctors left Kraslava with the Germans upon their retreat. After the World War II an even larger hospital was built with 100 beds, a number of departments, a clinical laboratory and a dispensary.

Medical facilities expanded after WWI. Fifteen beds were initially available in the hospital, later expanding to twenty. The doctors were Anton Kosminsky, Georg Serikov, Ernst Reinson, Leiba Mirvis, Nikolay Bokum and Janis Zerbuk. In addition a sanatorium opened in 1930 with 20 beds for the treatment of tuberculosis. The pharmacy was operated by the chemist by Samuel Shmuda, who would die during the murder of Kraslava's Jews in 1941. Under German occupation Janis Zerbuk continued to manage the hospital and later a new hospital with 60 beds was organised by Nikolay Bokum. Having collaborated with the Nazis, both these doctors left Kraslava with the Germans upon their retreat. After the World War II an even larger hospital was built with 100 beds, a number of departments, a clinical laboratory and a dispensary.

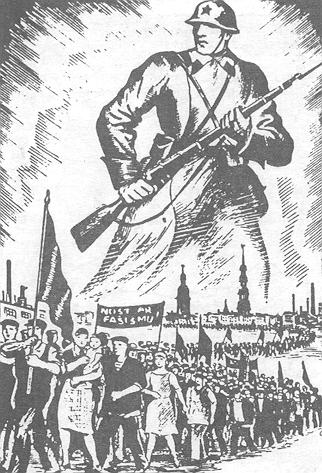

The First Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic

The division of spheres of influence between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany that formed the secret protocol of the Ribbentrop - Molotov non-aggression pact brought the Red Army to occupy Latvia on June 17th 1940. Immediately the previously illegal Latvian Communist party was legalised and the red flag raised above the public buildings of Kraslava. Vladislav Pozaucu was appointed mayor and on July 15th 1940 elections were held for the Saeima (parliament), the only party on the ballot paper being the Working Party block. After Latvia 'requested' its annexation to the USSR on August 5th 1940 the Saeima delegation returning from Moscow by train, stopping at railway stations along the line to conduct rallies with the local population. On reaching Kraslava the new leaders of the Latvian SSR, Augusts Kirhenshteins and Vilis Lacis, made speeches to the people of Kraslava to convince them of the benefits of the new regime.

The division of spheres of influence between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany that formed the secret protocol of the Ribbentrop - Molotov non-aggression pact brought the Red Army to occupy Latvia on June 17th 1940. Immediately the previously illegal Latvian Communist party was legalised and the red flag raised above the public buildings of Kraslava. Vladislav Pozaucu was appointed mayor and on July 15th 1940 elections were held for the Saeima (parliament), the only party on the ballot paper being the Working Party block. After Latvia 'requested' its annexation to the USSR on August 5th 1940 the Saeima delegation returning from Moscow by train, stopping at railway stations along the line to conduct rallies with the local population. On reaching Kraslava the new leaders of the Latvian SSR, Augusts Kirhenshteins and Vilis Lacis, made speeches to the people of Kraslava to convince them of the benefits of the new regime.

Communism brought change. Commercial enterprises were nationalised. Officials of the previous regime lost their positions. The educational curriculum adjusted itself to the Soviet system and religious education was prohibited. Children were encouraged to participate in the youth activities of Pioneer and Comsomol.

Anti-soviet activity was heavily punished. In September 1940 four pupils were arrested for hanging posters attacking the new regime. After their detention in the Dvinsk prison they were exiled to Siberia, along with twenty other residents. Many died in exile, the survivors returning after the war. With the imminent invasion of the Nazi forces the Red Army executed three leading Kraslava Catholics prior to their retreat.

Kirhenshteins

Communist Poster

Latvian SSR

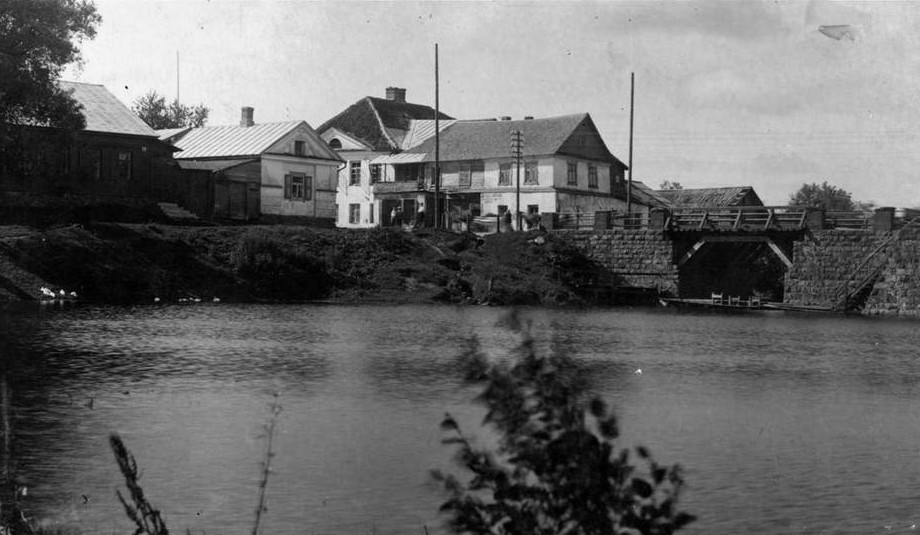

The Mill Pond on the Janupite Stream

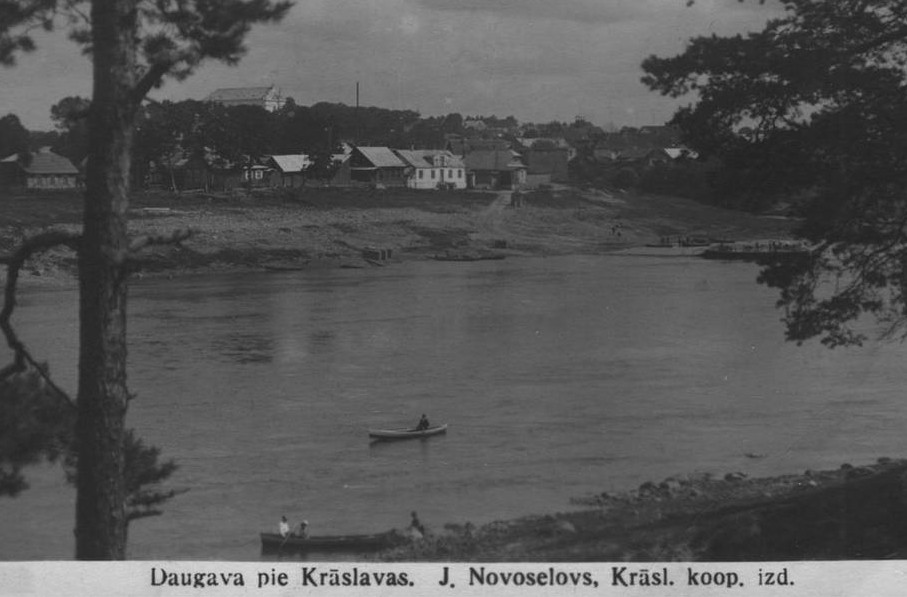

The Daugava (Dvina) River Floods Kraslava - 1931

World War II - Nazi Occupation of Kraslava and the Holocaust

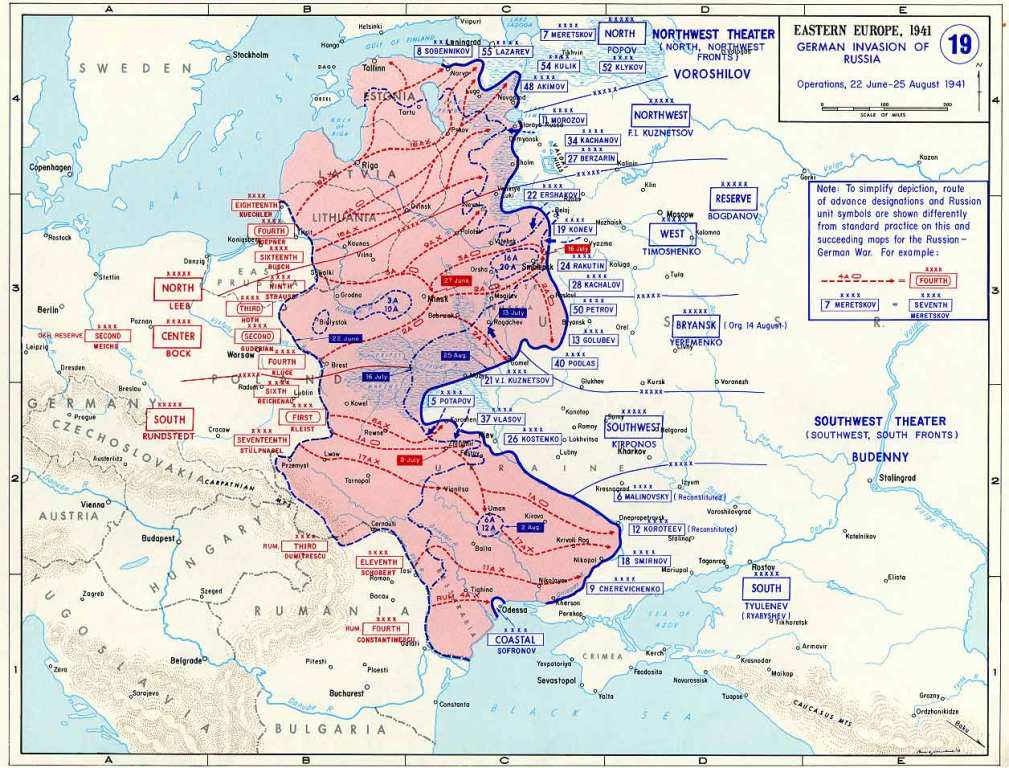

With the outbreak of fighting of Operation Barbarossa the 16th Army and the 4th Panzer Army of the Wehrmacht's Army Group North under Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb attacked the North-Western Front of the Red army commanded by General Colonel Fyodor Kuznetsov. The Germans advanced quickly, crossing the Daugava River close to Daugavpils, capturing the fortress and creating a bridgehead. Kraslava was bombarded, killing a number of civilians. Between the 1st to 4th July 1941 the 21st Mechanised Division and the Rifle Corp of the 27th Army of the Red Army who were stationed in the town, made a strategic retreat to the east and the Nazis occupied Kraslava.

With the outbreak of fighting of Operation Barbarossa the 16th Army and the 4th Panzer Army of the Wehrmacht's Army Group North under Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb attacked the North-Western Front of the Red army commanded by General Colonel Fyodor Kuznetsov. The Germans advanced quickly, crossing the Daugava River close to Daugavpils, capturing the fortress and creating a bridgehead. Kraslava was bombarded, killing a number of civilians. Between the 1st to 4th July 1941 the 21st Mechanised Division and the Rifle Corp of the 27th Army of the Red Army who were stationed in the town, made a strategic retreat to the east and the Nazis occupied Kraslava.

Ritter von Leeb

Kuznetzov

On the first day of the occupation a German officer was shot, bringing immediate retaliation against the inhabitants and the occupation forces began to arrest former Soviet activists and officials. Within a short period the Nazis moblised a force of Latvian auxiliary police (Schutzmannschaften), that was commanded by a local shop owner named Briedis who would later be appointed as the collaborationist mayor. Under Nazi auspicies brutal actions against the large population of Jewish citizens were speedily organised. Notices appeared instructing the Jews to collect for deportation and on the 29th July 1941 the local Latvian auxiliary police escorted them to the Ghetto in Daugavpils (Dvinsk). In mid-August

1941 the entire community of over 1300 Kraslava Jews was slaughtered by the Einsatzgruppen

Operation Barbarossa - The Nazi Invasion of the Soviet Union - June 22nd 1941

'A' in the Pogulanka Forest near Dvinsk. Full details of the Holocaust in Kraslava can be found here.

In 1942 fifty-one gentile residents were for moblised for forced labour in Germany and in the following year the Nazis organised special collaborationist Latvian detachments of the Waffen-SS to which many young Latvians were voluntarily mobilised.

Insignia of the Latvian Divisions of the Waffen-SS

Bagramyan & Marshal Vasilevski

In 1942 fifty-one gentile residents were for moblised for forced labour in Germany and in the following year the Nazis organised special collaborationist Latvian detachments of the Waffen-SS to which many young Latvians were voluntarily mobilised.

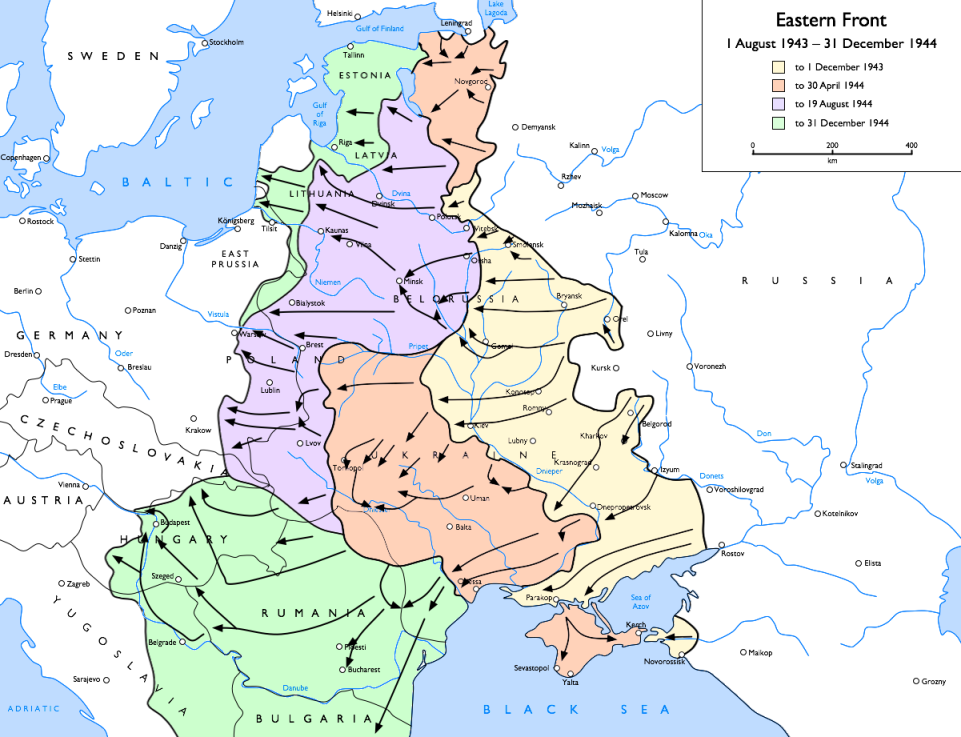

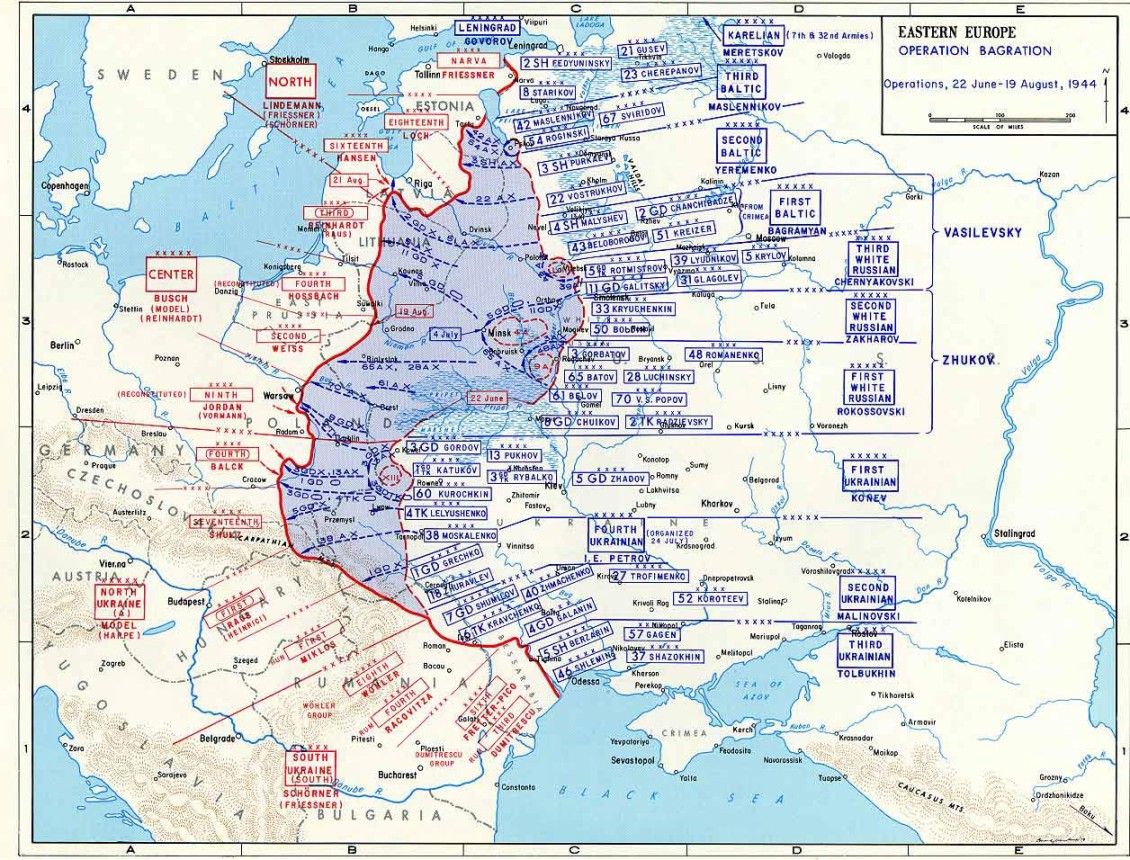

By the summer of 1944 Operation Bagration of the summer of 1944 enabled the Red Army to break down the German defences in Belarus, opening up the path to Latvia. On July 22nd 1944 the Baltic Front, commanded by Marshal Hovhannes Bagramyan ordered the 83rd rifle corps of the Fourth Shock Army

By the summer of 1944 Operation Bagration of the summer of 1944 enabled the Red Army to break down the German defences in Belarus, opening up the path to Latvia. On July 22nd 1944 the Baltic Front, commanded by Marshal Hovhannes Bagramyan ordered the 83rd rifle corps of the Fourth Shock Army

Battle for the Liberation of Kraslava - July 1944

led General P. F. Malyshev to attack German units near Kraslava. The Nazis soon retreated and the Soviets liberated Kraslava the same day. Briedis, the collaborationist official who had administered the town during the occupation, fled with the Nazis leaving documents listing the names of the Nazi

appointed police and other collaborators with the German regime. Lucian Gzhibovsky, a former mayor of Kraslava, entered the municipality offices to prevent the information from falling into the hands of the Red army, thus preventing proper retribution upon those whose hands had been tainted with collaboration during the years of Nazi control.

Red Army Counterattack - 1943-5

Operation Bagration - Summer 1944

The Second Period of Soviet Rule - 1944-`1991

Kraslava sustained little collateral damage during WWII, so reconstruction was minimal. Shortly after the red flag was raised over the public buildings policies of collectivisation were introduced and the typical patterns of Soviet life set in characterised by poor services, few consumer goods, long queues and the repression of Latvian and Latgalian cultural expression.

In the years following the war a number of monuments were dedicated for the victims of the German - Nazi occupation. A cenotaph for the fallen soldiers of the Red Army was built in the park, a memorial the Jewish victims of the holocaust on Udrisha Street, a memorial stone for the war dead was set opposite the Russian-Orthodox church and in 1965 an additional memorial was placed in the eastern part of the town.

Kraslava sustained little collateral damage during WWII, so reconstruction was minimal. Shortly after the red flag was raised over the public buildings policies of collectivisation were introduced and the typical patterns of Soviet life set in characterised by poor services, few consumer goods, long queues and the repression of Latvian and Latgalian cultural expression.

In the years following the war a number of monuments were dedicated for the victims of the German - Nazi occupation. A cenotaph for the fallen soldiers of the Red Army was built in the park, a memorial the Jewish victims of the holocaust on Udrisha Street, a memorial stone for the war dead was set opposite the Russian-Orthodox church and in 1965 an additional memorial was placed in the eastern part of the town.

The Lutheran Church

Typical Latgale Wooden Houses & Soviet Apartments

High School, Views and the Bridge

The Soviet House of Culture was built on Ratuzha Street, the Communist Party office was constructed (now the town council), a sport stadium was opened in the park and a flax factory was built on Riga Street. Further enterprises were added in the sixties and seventies - a wood plant, a building company, a dairy plant, a hotel, the 'Zarya' cinema, a department store and new school buildings. With the construction of modern blocks of flats in the town centre the characteristic image of a 'shtetl' of small wooden houses so typical of Latgale started to change.

Memorial to the Victims of Fascism

A new bridge across the Dvina was constructed in 1968, but it could be used only in the summer when the water level was low. At other times of the year a ferry still provided the only way to cross to the left bank. Only in 1994 was a permanent bridge opened and the ferry service ceased.

Kraslava - from 'Atmoda' to Renewed Independence

The Popular Front of Latvia exploited glasnost to raise the flag of 'Atmoda' (Latvian national awakening) for the third time. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union the Latvian flag was flown over the the chemist’s building in the Market Square on April 2nd 1988 and Latvian independence was restored on the 21st August 1991. The pre-war street names were restored and elections for the town council led to the election of a new Duma (council) and mayor. There are today 12000 residents in Kraslava.

The Popular Front of Latvia exploited glasnost to raise the flag of 'Atmoda' (Latvian national awakening) for the third time. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union the Latvian flag was flown over the the chemist’s building in the Market Square on April 2nd 1988 and Latvian independence was restored on the 21st August 1991. The pre-war street names were restored and elections for the town council led to the election of a new Duma (council) and mayor. There are today 12000 residents in Kraslava.

Republic of Latvia

Kraslava Today - The Renaissance of Latgalian Culture

Latgale

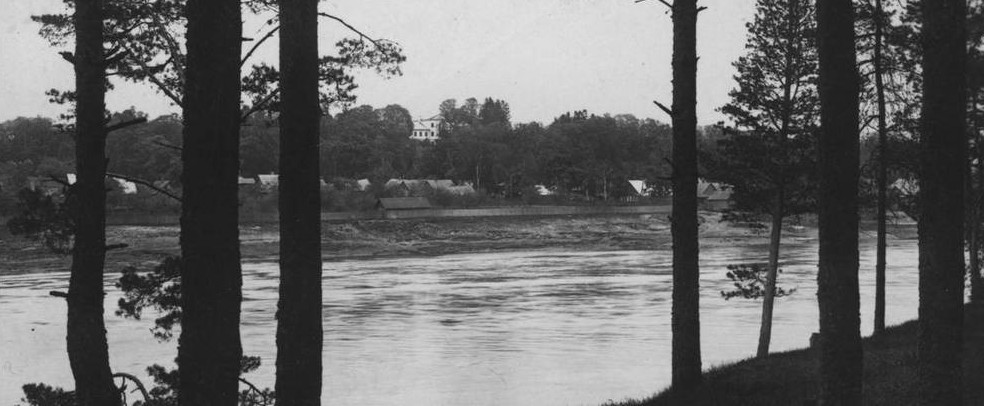

Old Views of the Daugava (Dvina) River

Views Over the Daugava (Dvina) River

Copyright © 2008 Jon Seligman. All Rights Reserved.

Sources

This is not an article researched from primary sources. Much of the bibliographical material available is written in Russian, Polish and Latvian and is thus not accessible to me. Please feel welcome to contact if you wish to correct or augment the information.

1 - There are a series of Wikipedia articles, many of them linked within the text. The page dedicated to Kraslava is very limited in scope.

2 - Kraslava. In. Dov Levin. 1988. Ed. Pinkas Hakehilot: Latvia ve Estonia. Yad Vashem. Jerusalem Pp. 226-233.(Hebrew).

3 - Kraslava municipal website - http://www.kraslava.lv/par_kraslavu/?L=1. Good history section, though section on Jewish community is very weak.

4 - Latgale Resarch Centre

5 - Latvia's Jewish Community: History, Tragedy, Revival; Leo Dribins, Armands Gutmanis, Margers Vestermani at the Latvian Foreign Ministry website.

This is not an article researched from primary sources. Much of the bibliographical material available is written in Russian, Polish and Latvian and is thus not accessible to me. Please feel welcome to contact if you wish to correct or augment the information.

1 - There are a series of Wikipedia articles, many of them linked within the text. The page dedicated to Kraslava is very limited in scope.

2 - Kraslava. In. Dov Levin. 1988. Ed. Pinkas Hakehilot: Latvia ve Estonia. Yad Vashem. Jerusalem Pp. 226-233.(Hebrew).

3 - Kraslava municipal website - http://www.kraslava.lv/par_kraslavu/?L=1. Good history section, though section on Jewish community is very weak.

4 - Latgale Resarch Centre

5 - Latvia's Jewish Community: History, Tragedy, Revival; Leo Dribins, Armands Gutmanis, Margers Vestermani at the Latvian Foreign Ministry website.

11

12