Sources

This is not an article researched from primary sources. Much of the bibliographical material available is written in Russian, Polish and Latvian and is thus not accessible to me. Please feel welcome to contact if you wish to correct or augment the information.

1 - There are a series of Wikipedia articles, many of them linked within the text. The page dedicated to Kraslava is very limited in scope.

2 - Kraslava. In. Dov Levin. 1988. Ed. Pinkas Hakehilot: Latvia ve Estonia. Yad Vashem. Jerusalem Pp. 226-233.(Hebrew).

3 - Latvia's Jewish Community: History, Tragedy, Revival; Leo Dribins, Armands Gutmanis, Margers Vestermani at the Latvian Foreign Ministry website.

This is not an article researched from primary sources. Much of the bibliographical material available is written in Russian, Polish and Latvian and is thus not accessible to me. Please feel welcome to contact if you wish to correct or augment the information.

1 - There are a series of Wikipedia articles, many of them linked within the text. The page dedicated to Kraslava is very limited in scope.

2 - Kraslava. In. Dov Levin. 1988. Ed. Pinkas Hakehilot: Latvia ve Estonia. Yad Vashem. Jerusalem Pp. 226-233.(Hebrew).

3 - Latvia's Jewish Community: History, Tragedy, Revival; Leo Dribins, Armands Gutmanis, Margers Vestermani at the Latvian Foreign Ministry website.

The first Rabbi Zalman Charif, who founded the community, was replaced by a series of rabbis: Rabbi Eliezer who led the community till 1810,Yosef - Yosele Charif, Rabbi Yizhak Zioni, son of Rabbi Naphtali Zioni of Lutzin, Moshe Klitzner of Warklian. In the mid 19th century Kraslava was officially under the pastoral guidance of the nearby shtetl Druya. In the early 20th century the Mitnaged Rabbi was was Yosef Rabinson, who was later replaced by his son-in-law Moshe David Shuv and the Chasidic Rabbi was Yaakov Kopel Klachkin. The two rabbis served through Latvian rule and died in the holocaust.

The Community Grows

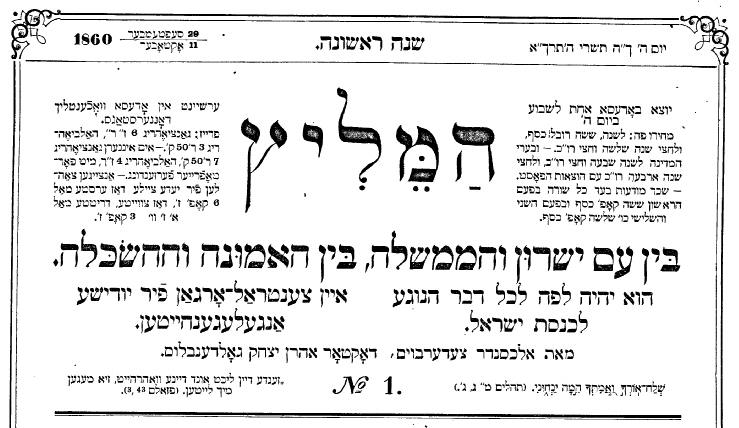

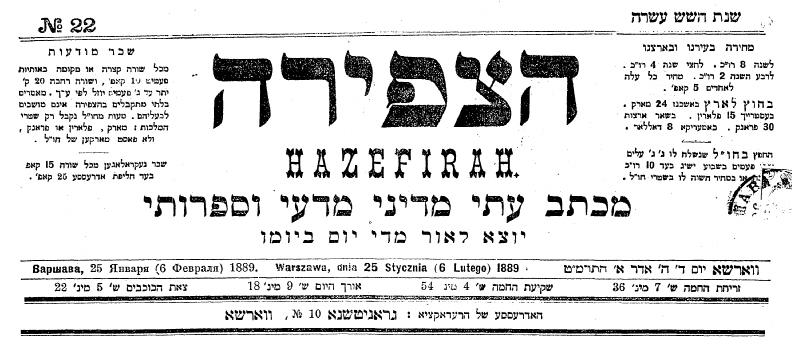

In second half of the nineteenth century the Jewish population increased further. In 1847 there were 1483 Jews and by 1897, 4051, some 51% of the town's population. The Jews lived mostly in the centre of Kraslava and along the main street; the Poles, Russians and Latvians living on the outskirts. Jewish newspapers, such as HaMelitz, gave insight into community fights between Mitnagdim and Chasidim; and arguments over contracts to tax Kosher meat (Korovka) the monies of which were used for the social aid and religious services. Hovevei Zion members in Kraslava encouraged readers of HaMelitz and HaTzfira to donate money to the building of Eretz Israel and to give preference for the Etrogs from Eretz Israel and not for those from Corfu. There were also heated discussions concerning religious observance showing that a relatively liberal attitudes were widespread in the community. Thus in 1863 there is debate concerning a secular Jew (Maskil) who refused to circumcise his son in spite of protests from the Rabbis and much of the community. Secularism took hold and at the start of the 20th century a secular school for boys was established by the teacher Levinson.

In second half of the nineteenth century the Jewish population increased further. In 1847 there were 1483 Jews and by 1897, 4051, some 51% of the town's population. The Jews lived mostly in the centre of Kraslava and along the main street; the Poles, Russians and Latvians living on the outskirts. Jewish newspapers, such as HaMelitz, gave insight into community fights between Mitnagdim and Chasidim; and arguments over contracts to tax Kosher meat (Korovka) the monies of which were used for the social aid and religious services. Hovevei Zion members in Kraslava encouraged readers of HaMelitz and HaTzfira to donate money to the building of Eretz Israel and to give preference for the Etrogs from Eretz Israel and not for those from Corfu. There were also heated discussions concerning religious observance showing that a relatively liberal attitudes were widespread in the community. Thus in 1863 there is debate concerning a secular Jew (Maskil) who refused to circumcise his son in spite of protests from the Rabbis and much of the community. Secularism took hold and at the start of the 20th century a secular school for boys was established by the teacher Levinson.

The Jews of Kraslava

55°54'N, 27°10'E

The Jewish Community of Kraslava

In 1897, the Vitebsk Guberniya of which Latgale was a part, had a total population of 240000, a quarter of them Jews. By WWI the 80000 Jews of the province forming the majority in most of the towns and cities including Dvinsk, Rezekne and Kraslava. The events of the war would led to massive depopulation of Latvia, many of the inhabitants becoming refugees, a phenomena that greatly reduced the number of Jews. Still in 1920 Daugavpils (Dvinsk) had 11824 Jews of a total of 28938 residents with al least 30 synagogues.

Latvian independence resulted in a major shift in the distribution of Jews. Initially Latgale had the largest concentration of Jews, with 30000 of the

Latvian independence resulted in a major shift in the distribution of Jews. Initially Latgale had the largest concentration of Jews, with 30000 of the

LATGALE

ZEMGALE

VIDZEME

COURLAND

RIGA

Russia

Lithuania

Belarus

The Jews of Latgale

Fleeing the Czarist repression of Ivan the Terrible Jews first settled in the Kraslava district of Latgale. By 1569 Latgale came under the control of the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth. Many Jews exploiting the more favorable attitudes of the Polish crown and took up residence in Latgale, some fleeing the anti-semitic pogroms of Bogdan Khmelnitsky. Communities or Kahals were established in Krustpils (Jekabpils), Dyneburg - Dvinsk (Daugavpils) and Kraslava. Most of the Jews of Latgale came from the Litvak tradition and looked to Vilna for religious guidance.

Being close to the borders with Russia the Jews in Latgale worked as customs collectors, as merchants in the towns, as traders in the rural areas, as artisans in trades and crafts and some as farmers of small holdings. Typical Jewish professions included: tanners, tailors, blacksmiths, locksmiths, shoemakers, watchmakers, glaziers, bakers, carpenters, butchers, weavers, fullers, storekeepers, merchants, pharmacists, and doctors. Jews received permits to run inns, often distilling the alcohol sold. Peddling too was considered a Jewish occupation, the travelers carrying their merchandise on their back or by horse from shtetl to shtetl. By 1784 5000 Jews resided in Latgale, 3698 of them registered as permanent residents.

Fleeing the Czarist repression of Ivan the Terrible Jews first settled in the Kraslava district of Latgale. By 1569 Latgale came under the control of the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth. Many Jews exploiting the more favorable attitudes of the Polish crown and took up residence in Latgale, some fleeing the anti-semitic pogroms of Bogdan Khmelnitsky. Communities or Kahals were established in Krustpils (Jekabpils), Dyneburg - Dvinsk (Daugavpils) and Kraslava. Most of the Jews of Latgale came from the Litvak tradition and looked to Vilna for religious guidance.

Being close to the borders with Russia the Jews in Latgale worked as customs collectors, as merchants in the towns, as traders in the rural areas, as artisans in trades and crafts and some as farmers of small holdings. Typical Jewish professions included: tanners, tailors, blacksmiths, locksmiths, shoemakers, watchmakers, glaziers, bakers, carpenters, butchers, weavers, fullers, storekeepers, merchants, pharmacists, and doctors. Jews received permits to run inns, often distilling the alcohol sold. Peddling too was considered a Jewish occupation, the travelers carrying their merchandise on their back or by horse from shtetl to shtetl. By 1784 5000 Jews resided in Latgale, 3698 of them registered as permanent residents.

Jewish estate managers, who maintained the holdings of the szlachta or poretz, were a cause for resentment by the exploited serfs. Similar hatred for Jews was generated by the activities of money-lenders, though the consequent anti-Semitism was misdirected toward the entire community.

The status of the registered Jewish citizens was determined by legal division according to profession. Merchants were granted the right to participate in the elections of city councils known as Duma. By the late 18th century over half of the urban residents in Latgale were Jews. Dvinsk, the region's largest town, was populated with 1373 Jews of of the city’s 2200 residents. One of the main causes for this were the restrictions applied by Catherine II in 1791 on the Jews in the Pale of Settlement, by which Jews were prevented from working the land, forcing them to migrate to the urban areas. Many Jews, who were coerced to live in the shtetlach, found themselves without work, living in poor housing and in deep poverty. The nineteenth century became a period of large population growth, a trend that deepened their economical hardship and fed social unrest.

Until 1844 the Jews of Latgale managed their affairs through the Kahal, self-governing institutions that collected taxes, maintained order, supervised observance of civil and religious law, ensured the enlistment of recruits, and took care of the sick and old people. During the rule of Alexander I and Nicholas I the Czarist-Russian government implemented measures with the intention of forcing them to give up their way of life and religion. The measures, that were implemented harshly within the Vitebsk Gurberniya, including Latgale, included the imposition of higher taxes on the kahal; the prohibition to change place of residence without permission; the enlistment of many Jewish boys to military cantons - where attempts were made to convert them to Orthodoxy; taxing Jews

The status of the registered Jewish citizens was determined by legal division according to profession. Merchants were granted the right to participate in the elections of city councils known as Duma. By the late 18th century over half of the urban residents in Latgale were Jews. Dvinsk, the region's largest town, was populated with 1373 Jews of of the city’s 2200 residents. One of the main causes for this were the restrictions applied by Catherine II in 1791 on the Jews in the Pale of Settlement, by which Jews were prevented from working the land, forcing them to migrate to the urban areas. Many Jews, who were coerced to live in the shtetlach, found themselves without work, living in poor housing and in deep poverty. The nineteenth century became a period of large population growth, a trend that deepened their economical hardship and fed social unrest.

Until 1844 the Jews of Latgale managed their affairs through the Kahal, self-governing institutions that collected taxes, maintained order, supervised observance of civil and religious law, ensured the enlistment of recruits, and took care of the sick and old people. During the rule of Alexander I and Nicholas I the Czarist-Russian government implemented measures with the intention of forcing them to give up their way of life and religion. The measures, that were implemented harshly within the Vitebsk Gurberniya, including Latgale, included the imposition of higher taxes on the kahal; the prohibition to change place of residence without permission; the enlistment of many Jewish boys to military cantons - where attempts were made to convert them to Orthodoxy; taxing Jews

Polish Noblemen - Szlachta

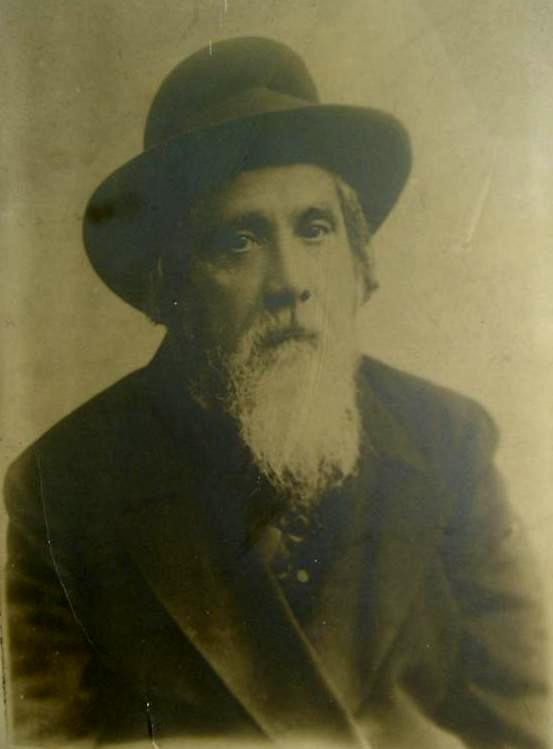

Orthodox Jews Adopted the Clothing of the Szlachta

Orthodox Jews Adopted the Clothing of the Szlachta

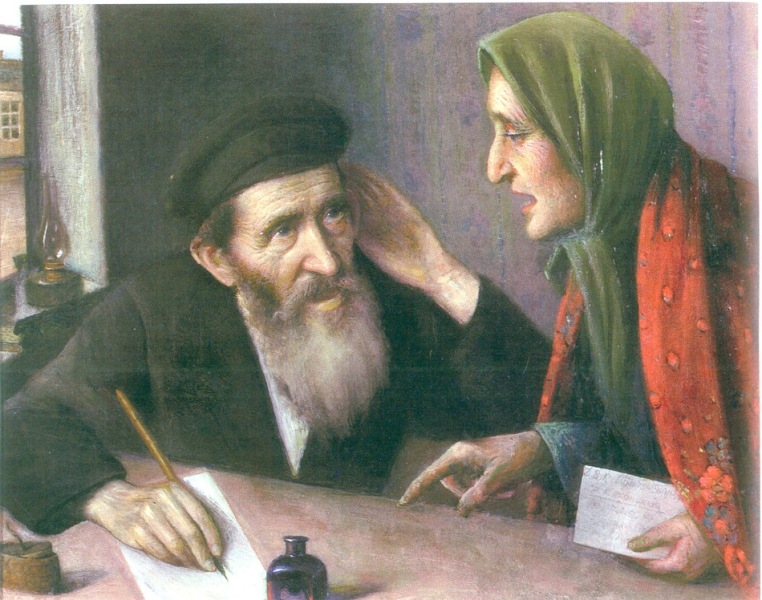

The Watchmaker

The Petitioner

Yehuda Pen - An artist of Dvinsk & Vitebsk and teacher of Chagall

Important Dvinsker Jews

for the right to wear their traditional clothing, etc. In 1844 a decree abolished the Kahal, placing Jews directly under general administration. During the thirty year reign of Nicholas I (1796-1855), 600 laws and decrees were passed regulating the life of Jews.

Cultural Revival & Political Activism

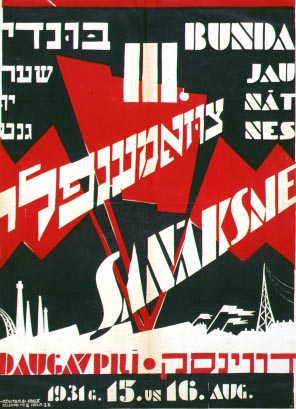

As elsewhere in Europe, Jews reacted to anti-Semitism ideologicaly with the rise of secular socialist and Zionist movements including Hovevei Zion, Zairei Zion, Mizrachi and the Bund, a social democratic union of Jews that was founded in Vilna, but with a large centre in Daugavpils. Jews took an active role in the 1905 revolution, fighting together with the revolutionary movement against the pogroms incited by Czarist agents and the Black Hundreds. Latvia was a centre of Jewish cultural revival, contributing to the Hebrew cultural renaissance at a level well beyond its size. This was facilitated by the cultural autonomy and religious freedom accorded to the community by independent Latvia, rights that continued, if in a restricted form, under the Ulmanis authoritarian regime established on May 15, 1934. Jewish and Zionist parties were successful in both national and municipal elections with

As elsewhere in Europe, Jews reacted to anti-Semitism ideologicaly with the rise of secular socialist and Zionist movements including Hovevei Zion, Zairei Zion, Mizrachi and the Bund, a social democratic union of Jews that was founded in Vilna, but with a large centre in Daugavpils. Jews took an active role in the 1905 revolution, fighting together with the revolutionary movement against the pogroms incited by Czarist agents and the Black Hundreds. Latvia was a centre of Jewish cultural revival, contributing to the Hebrew cultural renaissance at a level well beyond its size. This was facilitated by the cultural autonomy and religious freedom accorded to the community by independent Latvia, rights that continued, if in a restricted form, under the Ulmanis authoritarian regime established on May 15, 1934. Jewish and Zionist parties were successful in both national and municipal elections with

Dvinsk Great Synagogue

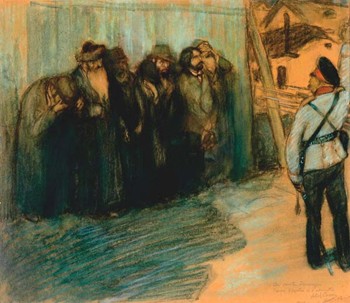

WWI Deportations - Abel Pann

total population of 79368 in Latvia. Over the following two decades many migrated to the capital forming a majority of Latvian Jews in Riga. By 1935 the number of Jews in Latgale had decreased to 27974.

Bund Poster - Daugavpils 1931

The Sixth Zionist Congress

members of the Bund, Socialist Zionists and Agudat Israel filling most of the seats. Riga would also become the cradle of Jabotinsky's Revisionist Zionism, its youth movement, Betar, being founded in city in 1923.

The Founding of the Jewish Community in Kraslava

In 1764 a small number of Jewish families moved to Kraslava on the invitation of Count Konstanty Ludwik Plater as part of his initiative to develop the town. The community, led by Rav Zalman Charif from Vilna, grew rapidly and by 1766 840 Jews were paying the head tax to the 'kahal' in Kraslava and the surrounding area. With the annexation of Latgale in 1772 to Russia, the 733 Jews of Kraslava formed half the shtetl's population. At the end of the eighteenth century Yaakov Eliyahu Frank was invited to settle in the town. He was a doctor from Germany, a student of the Haskalah movement and a follower of the ideas of Moshe Mendelssohn. Frank worked to improve the social and civil status of the Jews of Russia, petitioning the Czarist government through messages sent through the and Russian poet and politician Gavrila Derzhavin concerning the issue.

In 1764 a small number of Jewish families moved to Kraslava on the invitation of Count Konstanty Ludwik Plater as part of his initiative to develop the town. The community, led by Rav Zalman Charif from Vilna, grew rapidly and by 1766 840 Jews were paying the head tax to the 'kahal' in Kraslava and the surrounding area. With the annexation of Latgale in 1772 to Russia, the 733 Jews of Kraslava formed half the shtetl's population. At the end of the eighteenth century Yaakov Eliyahu Frank was invited to settle in the town. He was a doctor from Germany, a student of the Haskalah movement and a follower of the ideas of Moshe Mendelssohn. Frank worked to improve the social and civil status of the Jews of Russia, petitioning the Czarist government through messages sent through the and Russian poet and politician Gavrila Derzhavin concerning the issue.

| Trade | Owners | Employees | Apprentices | Total |

| Tailor Seamstress |

56 | 30 | 32 | 118 |

| Milner | 6 | 4 | 2 | 12 |

| Shirtmaker | 5 | 2 | 2 | 9 |

| Shoe Maker | 33 | 7 | 10 | 50 |

| Cloth Dyer | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Framer | 9 | 6 | 2 | 17 |

| Carpenter | 9 | 4 | 4 | 17 |

| Tin Maker | 6 | 3 | 0 | 9 |

| Glazier | 12 | 4 | 2 | 18 |

| Pig Bristle Cleaner | 11 | 22 | 20 | 53 |

| Oven Builder | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Flax Comber | 14 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| Candler | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Book Binder | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Watchmaker | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Coachman | 32 | 0 | 0 | 32 |

| Wood Cutter | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Baker | 21 | 6 | 0 | 27 |

| Barber | 5 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| Other Trades | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

Trades Survey of Kraslava Jews - 1887

Gavrila Derzhavin Count Plater

A 1887 statistical survey of the economic activities of the 426 Kraslava Jewish heads of households showed a wide range of activities; from typically Jewish professions such as tailors, to physical trades (coachmen, timber etc.) and the many bristle cleaners for the manufacture of brushes for export. Indeed, one of the largest employers was the Bristle Processing plant belonging to Chaim Churin that employed 200 workers, most of them Jews. Alongside the factory was a large cottage industry providing work for an additional 51 bristle cleaners in 1887 and 305 in 1900. Jews also worked in the tanning, flax and weaving industries. Kraslava was well known for the quality of its Matzot and for three months a year the bakers worked to supply the demand for the communities of Latgale. In 1901 a Credit Fund for Saving for Small Trades was founded to help shop owners and artisans.

The Kraslava Main Synagogue

The Kraslava Main Synagogue from across the Dvina River

The Synagogue is the large white building on the far left side of the picture.

The Synagogue is the large white building on the far left side of the picture.

The Big House of Prayer.

Signatures of the last Rabbis of Kraslava

HaMelitz & HaTzfira Newpapers

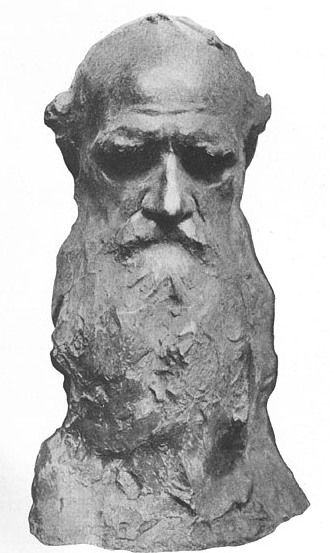

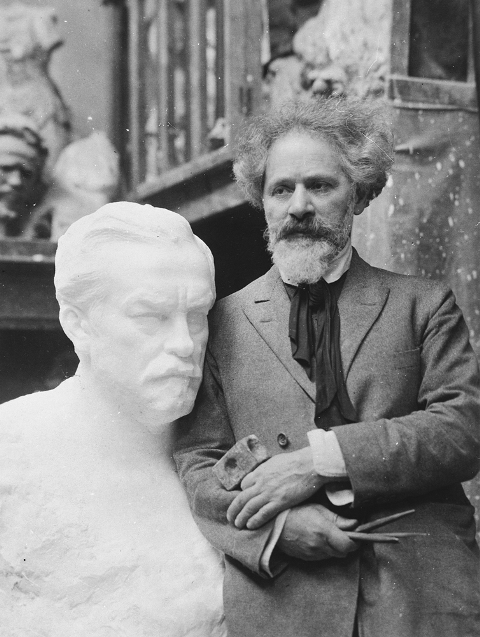

In 1893 half of Kraslava burnt, destroying 300 hundred houses including the two old synagogues. Aid for the homeless was collected for the desperate community by Yehudah Leib Aronson who mobilised his son, Naum, for the effort. Naum Aronson (see box), a well known sculptor working in Paris, raised funds from the French Rothschilds to aid Kraslava. Still, hardship and the loss of means of livelihood led many to emigrate during this period to America and South Africa.

sculpted portraits, monuments, and busts of prominent political and scientific figures, including Louis Pasteur, Spartacus, Rasputin, George Washington, Beethoven and Lenin. From 1897, his works were exhibited at the Salon du Champs de Mars, and later he joined the Salon's jury. As his reputation grew his work was displayed at the International Art Fair, Exposition Universelle in 1900. In 1913 Aronson returned to Kraslava, providing funds for a children's rehabilitation home. Aronson's works were also shown in Russia, and the artist made many visits to his homeland to supervise the installation of his sculptures, but anti-Semitism kept him from returning permanently. After the German occupation of France, Aronson and his wife emigrated to the USA in 1940. Aronson died in New York in 1943.

The Shtetl Burns

Streets of Kraslava

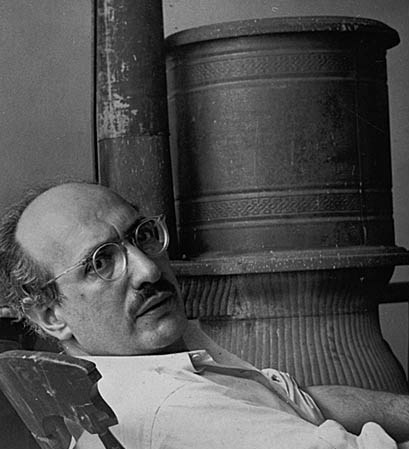

Naum Aronson

Naum Lvovich Aronson (1872-1943), was born in Kraslava to a large religious family. Sculpting from an early age, he left home at 16 to attend the art school of Ivan Trutnev in Vilna, but returned after less than a year because of anti-Semitism. In 1891 he decided to move to Paris to attend the Ecole des Arts Decoratifs, the studio of Professor H. Lemaire and the Colarossi private art school. Aronson's art was influenced by Michelangelo, Rodin and his Jewish background and many of his sculptures depict Jewish and biblical figures. After serving in the Russian army he returned to Paris in 1896 where he

Sculpture by Naum Aronson

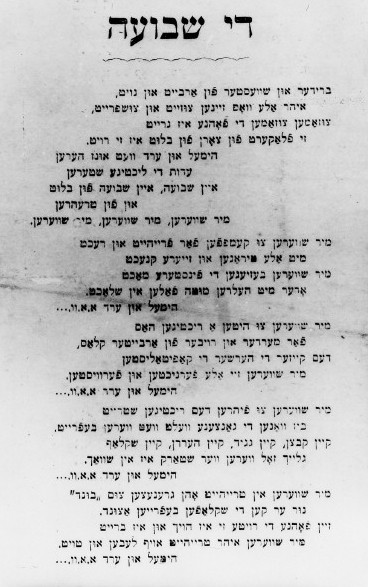

Bundist Oath (Shvua)

The Bund in Kraslava - 1932

Bundist Martyrs of the 1905 Revolution in Dvinsk

WWI - The Depopulation of Kraslava

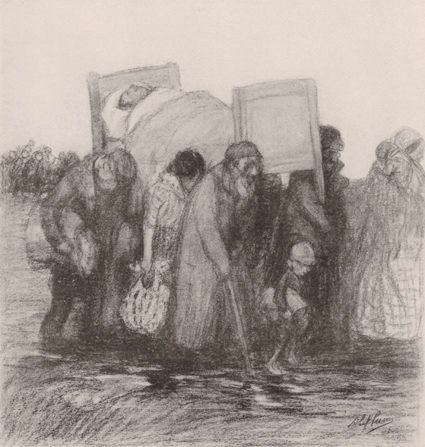

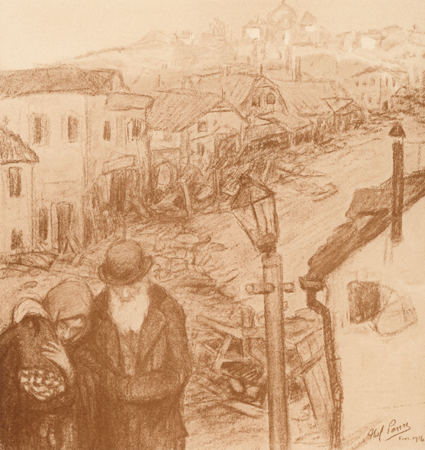

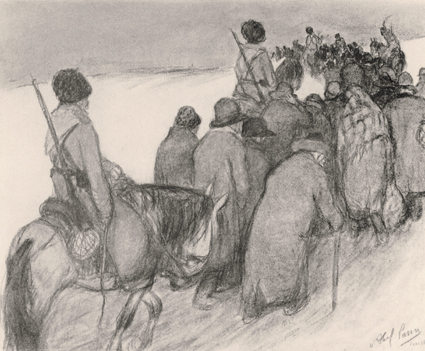

World War I left Kraslava and the surrounding region in deep social, physical, demographic and economic crisis. Russian anti-Semitism and the deportations of Jews to the east turned many of Kraslava's Jews into refugees, a situation illustrated by the artist Abel Pann, a son of the community. After the Germans occupied the town they mobilized many people for war work, again evacuating much of the civilian population. With the cessation of hostilities only a third of the pre-war community of 5000 Jews returned to their homes. The borders had

World War I left Kraslava and the surrounding region in deep social, physical, demographic and economic crisis. Russian anti-Semitism and the deportations of Jews to the east turned many of Kraslava's Jews into refugees, a situation illustrated by the artist Abel Pann, a son of the community. After the Germans occupied the town they mobilized many people for war work, again evacuating much of the civilian population. With the cessation of hostilities only a third of the pre-war community of 5000 Jews returned to their homes. The borders had

Deportations of Jews during WWI

'The Pitcher of Tears', by Abel Pann, Jerusalem 1926

'The Pitcher of Tears', by Abel Pann, Jerusalem 1926

Zionism

At the beginning of the 20th century Zionist organisations were also active. A branch of the socialist-zionist Poale Zion organisation was founded in 1901 and as noted before, took an active role in the self-defense organisation. The council of Poale Zion in Vilna in 1903 included a delegate from Kraslava and the aliyah of its members is illustrated by the inclusion of a Miss Posner from Kraslava as a delegate from Eretz Israel elected to the seventh Zionist Congress in Basle in 1905.

At the beginning of the 20th century Zionist organisations were also active. A branch of the socialist-zionist Poale Zion organisation was founded in 1901 and as noted before, took an active role in the self-defense organisation. The council of Poale Zion in Vilna in 1903 included a delegate from Kraslava and the aliyah of its members is illustrated by the inclusion of a Miss Posner from Kraslava as a delegate from Eretz Israel elected to the seventh Zionist Congress in Basle in 1905.

Guttman Joffe & the Bund

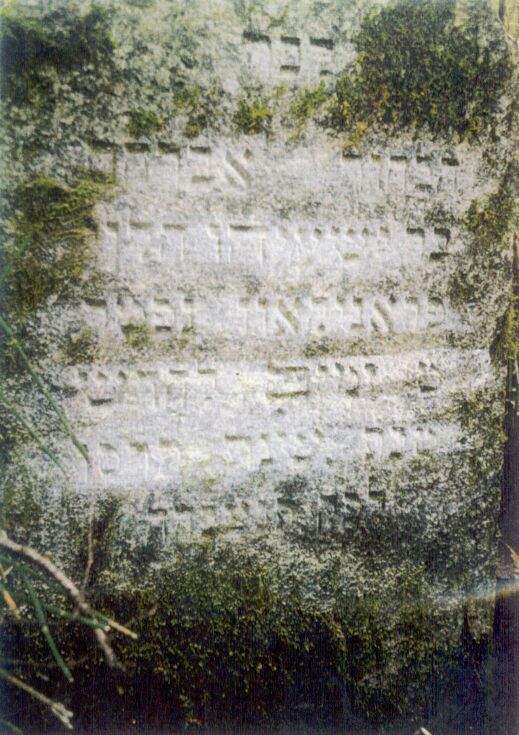

Guttman Joffe's involvement with the Brashter and Bundist disturbances in Kraslava at the turn of the twentieth century is part of family lore. Though much of the detail has been lost or embellished we can recount at least part of the story. Ginger haired Guttman was a brush maker in the Churin factory. Though probably a member of the Brashter Union or the Bund he was not an activist. Still he was a keen card-player, often playing cards with leading members of the Bund at his home. This activity did not go unnoticed by the Czarist police who probably thought that the Joffe home was being used for Bundist meetings. After the strike at the Churin factory in 1906, Guttman, together with other activists, was arrested and taken to the Dvinsk prison. A Bundist inspired riot broke out at the prison but Guttman, a political innocent, was protected from the gun shots of the prison guards by his card-playing comrades. In 1909 Guttman died of cholera in Kraslava.

Guttman Joffe & his Grave in Kraslava

Industrial and political agitation continued through the coming years. In 1906 there were again violent clashes involving the Brashter Union and workers from the Churin factory. During the incident workers occupied the factory until the government intervened and despatched a regiment of Cossacks to Kraslava. The soldiers

cleared the factory, attacked the Jewish workers and jailed many of the workers and activists in the prison in Dvinsk - including Guttman Joffe who was arrested for allowing Bundist activities in his home. Freidman, the head of the Union, was arrested and sentenced to hard labour. Still the struggle renewed in the autumn and finally the work day was reduced to 8 hours.

changed leaving the town in independent Latvia, with Russia to the east and Poland to the south. Kraslava was now separated from its natural economic hinterland. War had led to the closure of the Churin bristle factory and many of the workshops. Workers with no other skills became pedlars and others made a living by farming small holdings. With the severing of historical trading routes, Kraslava was no longer a transit point for timber along the Dvina between Vitebsk to the west through Riga. During the post war years only a few hundred of the three thousand refugees returned to Kraslava.

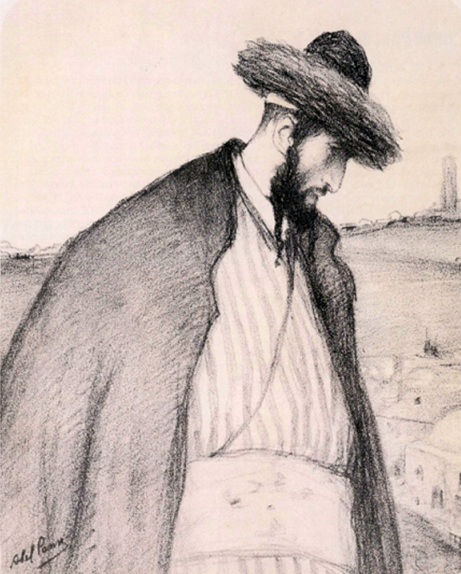

Abel Pann (1883 - 1963) was born in Kraslava as Abba Pfeffermann. After studying with Yehuda Pen in Vitebsk, who had also taught Chagall, he worked as a sign painter. In 1898 he travelled to study at the Academy of Fine Arts in Odessa and in 1903 continued his education at the Grande Chaumiere Academy in Paris and then traveled between Russia, Poland, Paris, Egypt and Palestine. In 1913 Boris

Abel Pann

Shatz invited Pann to teach at the Bezalel Academy of Art in Jerusalem. During WWI he became stranded in Paris and on hearing of the deportations and pogroms taking place in Russia, he drew a series of paintings on that theme known as the 'Pitcher of Tears'. However, the Russian Embassy in Paris succeeded in convincing the French authorities to prevent the printing.

In 1920, Pann returned to Palestine to settle permanently and until 1924 taught at Bezalel. In 1921, he established the first lithographic installation in Palestine, where lithographs of his works were made from a printing machine he had imported from Vienna.

Pann is considered a member of the founding

Pann is considered a member of the founding

The Bedouin in the Desert

generation of Israeli artists and best known as one of the most committed exponents of the Zionist art in its early days. It was in Jerusalem that Pann decided to devote himself to the paintings of the bible, which is considered to be the core of his oeuvre, founded deeply in the iconography of 19th century Orientalism.

Abel Pann died in Jerusalem in 1963

Abel Pann died in Jerusalem in 1963

Firing Squad

Sarai

Four Matriarchs

Chasid

| Trade Branch | No. of Firms |

| Grocery | 30 |

| Grain & Flour | 14 |

| Bread & Patisserie | 6 |

| Meat & Poultry | 11 |

| Fish | 4 |

| Ready Made Clothes | 9 |

| Cloth & Weaves | 13 |

| Leather & Shoes | 16 |

| Building Supplies & Paint | 11 |

| Tobacco & Liquor | 6 |

| Metal Goods | 15 |

| Buttons & Haberdashery | 24 |

| Kitchenware & Agricultural Supplies | 6 |

| Watchmaker & Jewelry | 12 |

| Barbers | 6 |

| Zionist Congress | Year | General Zionists | Zairei Zion | Socialist Zionists | HaZohar | Mizrachi | Total |

| 16 | 1927 | 2 | 26 | 28 | |||

| 17 | 1929 | 1 | 45 | 15 | 1 | 14 | 76 |

| 18 | 1933 | 33 | 169 | 24 | 63 | 289 | |

Public and Political Life

In the twenties the Bund was still Kraslava's strongest jewish party, though it slowly lost strength to the Zionists, especially among the youth who were attracted to solutions beyond the limitations of the shtetl. In the elections to the Latvian Saeima (Parliament) in 1925 the

In the twenties the Bund was still Kraslava's strongest jewish party, though it slowly lost strength to the Zionists, especially among the youth who were attracted to solutions beyond the limitations of the shtetl. In the elections to the Latvian Saeima (Parliament) in 1925 the

Kraslava Zionist Voting for the Zionist Congresses

Bund received 274 votes, 248 given to the ultra-Orthodox Agudath Israel party and 186 to the socialist-zionist Zairei Zion party. Zionist youth movements arose including Bnei Zion, HaTechiah and Bar Kochva, which were replaced in the thirties by the large pioneering movements - Gordonia, HaShomer HaZair, Noar Borochov (Dror) and HeHalutz which provided cadre for the various splinter groups of socialist-zionist parties. Though Latvia was the home of the Revisionist Zionism, its branch in Kraslava (HaZohar)

was small in numbers. After the outlawing of the Zionist organisations in the Soviet Union, the Zionist youth of Kraslava actively helped illegal immigrants of HeHalutz from the Vitebsk region of USSR on their way to Palestine. They absorbed the escapees and provided them with money and documentation before transferring them to Dvinsk and Riga. The largest Zionist party was Zairei Zion, which later became the Union of Socialist Zionists (ö"ñ), under the leadership of the Hebrew teacher Azriel Plakchin, a predominance clearly shown in the voting patterns for the Zionist Congresses. From 1934 till the Soviet invasion in 1939, the dictatorship under Karlis Ulmanis banned the activites of all political parties in Latvia, and Zionist party activism went underground.

HeChalutz Hachshara - Communal Training Farm in Kraslava

Many members of the Zionist youth movements joined Hachsharot, preparatory cooperative farms, with intention of making Aliyah to Kibbutzim in Eretz Israel. Two hundred Kraslavers left for mandatory Palestine in the thirties, mostly as Chalutzim (Pioneers). More still emigrated to South Africa and the USA.

A large group of Jewish youth were committed Communists and were the largest group in Comsomol - the Communist Youth Union which operated illegally. The Comsomol used the leftist-yiddish 'Culture League' as a cover for its activities. One of the leaders was the son of Azriel Plakchin. Comsomol members were arrested and tried from time to time, some using the proximity of the USSR border for escape in the opposite direction to their Zionist brothers.

A large group of Jewish youth were committed Communists and were the largest group in Comsomol - the Communist Youth Union which operated illegally. The Comsomol used the leftist-yiddish 'Culture League' as a cover for its activities. One of the leaders was the son of Azriel Plakchin. Comsomol members were arrested and tried from time to time, some using the proximity of the USSR border for escape in the opposite direction to their Zionist brothers.

Comsomol - 1930

Karlis Ulmanis

Teaching Seminar - Kraslava, 1928

Municipal Life & the Reappearance of Anti-Semitism

Jews formed the largest national community bloc in the city council (8 councillors of 20) and Moisei Rabinovitch from the Bund served from 1921 until 1932, as vice-mayor, and later as mayor of Kraslava. Among his achievements was the initiative tp grant Kraslava the status of a city. and the development of the city emblem - a boat with five oars, symbolising the five national communities of Kraslava: Jews, Poles, Russians, Latvians and Belorussians.

Until the mid-30s good relations existed between the Jews and the rest of Kraslava's population. Even Eliyahu Drey who as a Bund member had been arrested for assassinating the Chief of Police during Czarist times served on the council.

The early thirties brought unrest to Latvia, encouraged by the anti-Semitic activities of the fascist Perkonkrusts (Thunder Cross) Party. In 1933 rumours spread of imminent anti-Semitic riots. A Christian maid in a Jewish

Jews formed the largest national community bloc in the city council (8 councillors of 20) and Moisei Rabinovitch from the Bund served from 1921 until 1932, as vice-mayor, and later as mayor of Kraslava. Among his achievements was the initiative tp grant Kraslava the status of a city. and the development of the city emblem - a boat with five oars, symbolising the five national communities of Kraslava: Jews, Poles, Russians, Latvians and Belorussians.

Until the mid-30s good relations existed between the Jews and the rest of Kraslava's population. Even Eliyahu Drey who as a Bund member had been arrested for assassinating the Chief of Police during Czarist times served on the council.

The early thirties brought unrest to Latvia, encouraged by the anti-Semitic activities of the fascist Perkonkrusts (Thunder Cross) Party. In 1933 rumours spread of imminent anti-Semitic riots. A Christian maid in a Jewish

Moisei Rabinovitch

Mayor of Kraslava

Mayor of Kraslava

household had committed suicide and an anti-Semitic doctor disseminated a rumour that she had been murdered by Jews, inciting peasants to plan an attack on the Jews on the following Market Day. Word reached thecommunity of the intentions of the anti-Semites and a self-defense group organised, again deterring the attackers from their objective.

The Latvian population in Latgale was only a small minority. Ulmanis, who espoused the slogan 'Latvia for Latvians', adopted a policy directed toward eliminating the minority groups from economic life. As the result, the economic share of the minorities (Germans, Russians, Lithuanians and Jews) declined. Official policy existed to increase the number of Latvian residents in the area and to positively discriminate in favour of Latvian language and culture. Regulations intended to promote this policy hit the Jews hardest. The Jewish mayor of Kraslava was removed and a Latvian appointed. The new Mayor, well known for his anti-Semitic attitudes, immediately started policies of discrimination against the Jewish residents of the town, affecting especially their livelihood and educational prospects.

The Latvian population in Latgale was only a small minority. Ulmanis, who espoused the slogan 'Latvia for Latvians', adopted a policy directed toward eliminating the minority groups from economic life. As the result, the economic share of the minorities (Germans, Russians, Lithuanians and Jews) declined. Official policy existed to increase the number of Latvian residents in the area and to positively discriminate in favour of Latvian language and culture. Regulations intended to promote this policy hit the Jews hardest. The Jewish mayor of Kraslava was removed and a Latvian appointed. The new Mayor, well known for his anti-Semitic attitudes, immediately started policies of discrimination against the Jewish residents of the town, affecting especially their livelihood and educational prospects.

The Soviet Occupation - 1939 to 1941

After the Soviets dismantled the Latvian state Kraslava came under their wing. Now subject to the new communist policies, community institutions were closed, including the Chevra Kadisha which was closed by Government order in December 1940. A number of Jews took a leading role in the new regime after emerging from the communist underground that existed under Ulmanis. Non-communist organisations were not initially dismantled and the new authorities tried to attract Socialist - Zionist activists to the communist side. They encouraged them to participate in marches of the new regime and members of HaShomer Hazair marched in the demonstrations as a separate unit under their own flags and banners. With time the initial tolerance dissipated and the youth were pressured to join Comsomol and participate in exclusively Communist Party activities.

After the Soviets dismantled the Latvian state Kraslava came under their wing. Now subject to the new communist policies, community institutions were closed, including the Chevra Kadisha which was closed by Government order in December 1940. A number of Jews took a leading role in the new regime after emerging from the communist underground that existed under Ulmanis. Non-communist organisations were not initially dismantled and the new authorities tried to attract Socialist - Zionist activists to the communist side. They encouraged them to participate in marches of the new regime and members of HaShomer Hazair marched in the demonstrations as a separate unit under their own flags and banners. With time the initial tolerance dissipated and the youth were pressured to join Comsomol and participate in exclusively Communist Party activities.

Tombstones in the Jewish Cemetery

Still most of the Zionist youth remained loyal and tried to avoid participation, leading some to flee to Riga to avoid political and economic persecution. In June 1941 some of the richer Jews of Kraslava were exiled to Siberia, something that would paradoxically save their lives.

German Repression and the Holocaust

The Nazis attacked the Soviet Union on the 22nd June 194, occupying Kraslava a few days later. Within two months the Kraslava Jewish community was expeled to Daugavpils (Dvinsk) and then taken to the death pits in the Pogulanka forest. Save a few survivors, by August 1941 three centuries of Jewish history in Kraslava came to an end.

Read about the Holocaust in Kraslava here.

The Nazis attacked the Soviet Union on the 22nd June 194, occupying Kraslava a few days later. Within two months the Kraslava Jewish community was expeled to Daugavpils (Dvinsk) and then taken to the death pits in the Pogulanka forest. Save a few survivors, by August 1941 three centuries of Jewish history in Kraslava came to an end.

Read about the Holocaust in Kraslava here.

Copyright © 2008 Jon Seligman. All Rights Reserved.