Copyright © 2007-2014 Jon Seligman. All Rights Reserved.

Controversy exists over the origin of the name Gillis. Some suggest that it derives from the patronymic Hillel, while another proposal bases the name on the more unusual matronymic Geula.

The association of Gillis with Hillel, meaning 'praise' in Hebrew, is given credence by Alexander Beider in his important study of Jewish names in Russia. The transferal in Russian of the letter H to G produces names such as Kagan from Cohen and Gurwitz from Hurwitz, and here shifts Hillel to Gillel and then to Gillis. Fair enough but the second explanation, correct or not, is more interesting.

Gillis may well be a name given in honour of the matriarch of the family as a derivative of Geula, meaning deliverance in Hebrew. This name is often given to girls born during Pesach, alluding to the deliverance of the People of Israel from the hands of the Egyptians. There is usually a compelling reason to name a family after a woman's given name. Matronymics may be traced to a Jewish mother of heroic proportions, who probably overshadowed her husband, or my denote that a woman was widowed while young and then raised the fatherless children without remarrying. So the literal meaning of Gillis, according to this explanation, is the 'descendents of Geula'.

Note that not all Gillises are from Jewish families as the name appears in a quite unrelated identical spelling in Scotland. Significantly, from the limited research I have conducted it appears that all Jewish Gillises originated in the area around Kretinga and all are probably related.

The association of Gillis with Hillel, meaning 'praise' in Hebrew, is given credence by Alexander Beider in his important study of Jewish names in Russia. The transferal in Russian of the letter H to G produces names such as Kagan from Cohen and Gurwitz from Hurwitz, and here shifts Hillel to Gillel and then to Gillis. Fair enough but the second explanation, correct or not, is more interesting.

Gillis may well be a name given in honour of the matriarch of the family as a derivative of Geula, meaning deliverance in Hebrew. This name is often given to girls born during Pesach, alluding to the deliverance of the People of Israel from the hands of the Egyptians. There is usually a compelling reason to name a family after a woman's given name. Matronymics may be traced to a Jewish mother of heroic proportions, who probably overshadowed her husband, or my denote that a woman was widowed while young and then raised the fatherless children without remarrying. So the literal meaning of Gillis, according to this explanation, is the 'descendents of Geula'.

Note that not all Gillises are from Jewish families as the name appears in a quite unrelated identical spelling in Scotland. Significantly, from the limited research I have conducted it appears that all Jewish Gillises originated in the area around Kretinga and all are probably related.

Ashkenazi Jewish family names are a relatively modern phenomena. Modern states like surnames. Surnames make the clear identification of people for their control easier, especially for purposes of taxation and military recruitment. Family names had first become obligatory in 1787 in Austria and later in the German states. Meanwhile, in Czarist Russia, Peter the Great was attempting to organise his huge lands through policies of modernisation and centralisation. He had also embarked on the absorption of the territories of the Pale of Settlement - today an area covering Belarus, parts of Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Ukraine.

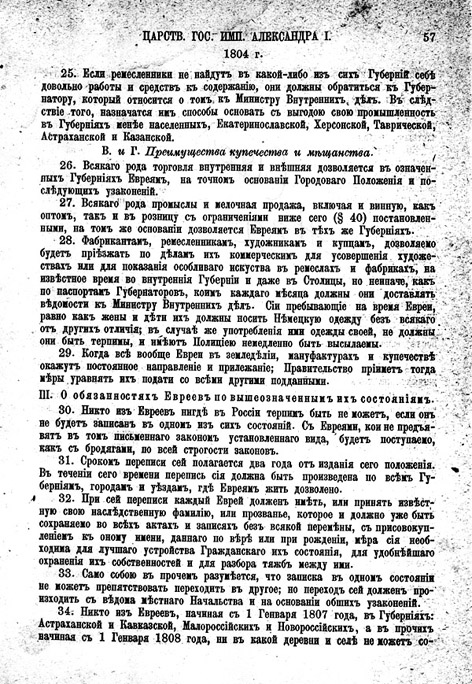

On December 9, 1804, Czar Alexander I issued the "Imperial Statute Concerning the Organization of Jews" (Vysochaishe utverzhdennoe Polozhenie. - O ustroistve Evreev). Article 32 of the edict reads: "Every Jew must have or adopt an inherited last name, or nickname, which should be used in all official acts and records without change."

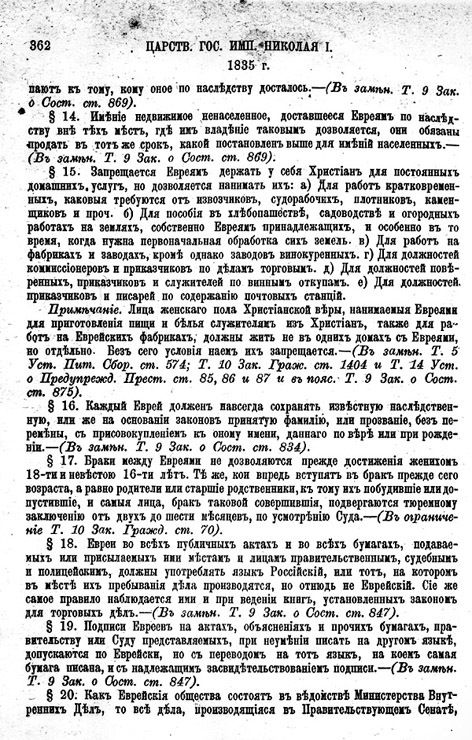

In practice the adoption of surnames does not seem to be rigorously enforced. Soon the collection of tax and from 1827, the mandatory conscription of Jews into the Czarist army, made the adoption of a family name a bureaucratic necessity. A further statute, issued on May 31 1835, by Czar Nicholas I, required "Every Jew, in addition to a first name given at a profession of faith or birth, must forever retain, without alteration, a known inherited or legally adopted surname or nickname."

Many of the new names followed the same pattern of formulation, as names were adopted in an almost collective procedure at the same time. These patterns were encouraged by the government seeking as much uniformity as possible. Prior to the statutes, Jews would adopt a patronymic name, David Meir ben Arie Leibe for example. The new names taken by the Jews in the Pale of Settlement were based on the patronymic or matronymic, trades, places of origin, given names, personality traits, items, geographical features and community names such as Cohen or Katz. Names were often rounded off with a Russian, Polish or German suffix, such as -man, -witz, -sohn, -berg or -ski. The Jews considered the use of a surname a gentile practice, so continued to use patronymic within the Jewish Community itself, while the surname was utilised for official business like census, deeds, passports and later for emigration.

For genealogical research the adoption of unique surnames makes the tracing of family through public records possible, while the patronymic documentation found within the community archives is nigh on impossible to exploit.

On December 9, 1804, Czar Alexander I issued the "Imperial Statute Concerning the Organization of Jews" (Vysochaishe utverzhdennoe Polozhenie. - O ustroistve Evreev). Article 32 of the edict reads: "Every Jew must have or adopt an inherited last name, or nickname, which should be used in all official acts and records without change."

In practice the adoption of surnames does not seem to be rigorously enforced. Soon the collection of tax and from 1827, the mandatory conscription of Jews into the Czarist army, made the adoption of a family name a bureaucratic necessity. A further statute, issued on May 31 1835, by Czar Nicholas I, required "Every Jew, in addition to a first name given at a profession of faith or birth, must forever retain, without alteration, a known inherited or legally adopted surname or nickname."

Many of the new names followed the same pattern of formulation, as names were adopted in an almost collective procedure at the same time. These patterns were encouraged by the government seeking as much uniformity as possible. Prior to the statutes, Jews would adopt a patronymic name, David Meir ben Arie Leibe for example. The new names taken by the Jews in the Pale of Settlement were based on the patronymic or matronymic, trades, places of origin, given names, personality traits, items, geographical features and community names such as Cohen or Katz. Names were often rounded off with a Russian, Polish or German suffix, such as -man, -witz, -sohn, -berg or -ski. The Jews considered the use of a surname a gentile practice, so continued to use patronymic within the Jewish Community itself, while the surname was utilised for official business like census, deeds, passports and later for emigration.

For genealogical research the adoption of unique surnames makes the tracing of family through public records possible, while the patronymic documentation found within the community archives is nigh on impossible to exploit.

What's in a Name ?

Statute Concerning the Organization of Jews" of 1804.

Article 32 states, "Every Jew must have or adopt an inherited last name, or nickname, which should be used in all official acts and records without change."

Article 32 states, "Every Jew must have or adopt an inherited last name, or nickname, which should be used in all official acts and records without change."

The Formulation of Jewish Surnames

Statute Concerning the Organization of Jews of 1835.

Article 16 states, "Every Jew, in addition to a first name given at a profession of faith or birth, must forever retain, without alteration, a known inherited or legally adopted surname or nickname."

Article 16 states, "Every Jew, in addition to a first name given at a profession of faith or birth, must forever retain, without alteration, a known inherited or legally adopted surname or nickname."

Gillis,

Hillel the Elder

Although the name Hillel is first found in Judges 12:13, it is Hillel the Elder that is the significant carrier of this name as one of the good guys of Jewish history.

As a famous religious leader, living in Jerusalem during the time of King Herod, Hillel is one of the most important figures associated with the Mishnah and the Talmud. He was the founder of the Beit Hillel school, a school for Tannaim (Sages of the Mishnah); and the founder of a dynasty of sages who led the Jews living in Eretz Israel until about the 5th century CE.

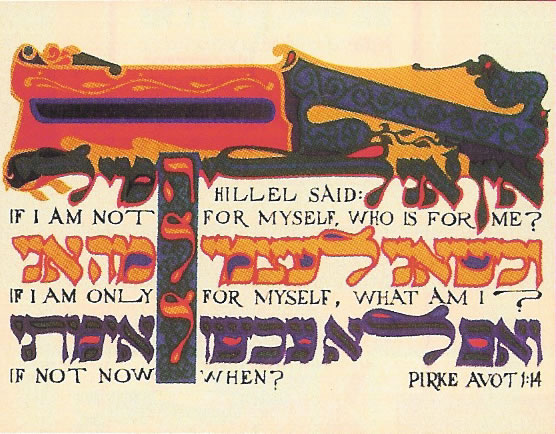

His two best-known statements are basic tenets of humanistic Judaism:

If I am not for myself, who will be? If I am only for myself, what am I? And if not now, when? (Pirkei Avot 1:14)

And the so-called ‘Golden Rule’:

That which is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow. That is the whole Torah; the rest is the explanation. (Babylonian Talmud, tractate Shabbat 31a).

As a famous religious leader, living in Jerusalem during the time of King Herod, Hillel is one of the most important figures associated with the Mishnah and the Talmud. He was the founder of the Beit Hillel school, a school for Tannaim (Sages of the Mishnah); and the founder of a dynasty of sages who led the Jews living in Eretz Israel until about the 5th century CE.

His two best-known statements are basic tenets of humanistic Judaism:

If I am not for myself, who will be? If I am only for myself, what am I? And if not now, when? (Pirkei Avot 1:14)

And the so-called ‘Golden Rule’:

That which is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow. That is the whole Torah; the rest is the explanation. (Babylonian Talmud, tractate Shabbat 31a).

"If I am not for myself, who will be? If I am only for myself, what am I? And if not now, when?"

Hillel the Elder

The Origin of the Name Gillis

The Gillis Family of Kretinga