Jerusalem of South Africa

Oudtshoorn - History

33°35'S 22°12'E

Oudtshoorn - Ostrich Capital of The World

Oudtshoorn is the most surprising Litvak shtetl of them all!

Oudtshoorn, a small town in South Africa’s Cape Province, became the new home for a thriving Litvak community, including Solomon Gillis who made his way from Kretinga to make his fortune during the Ostrich feather boom during the last two decades of the nineteenth century and up until World War I.

Oudtshoorn, a small town in South Africa’s Cape Province, became the new home for a thriving Litvak community, including Solomon Gillis who made his way from Kretinga to make his fortune during the Ostrich feather boom during the last two decades of the nineteenth century and up until World War I.

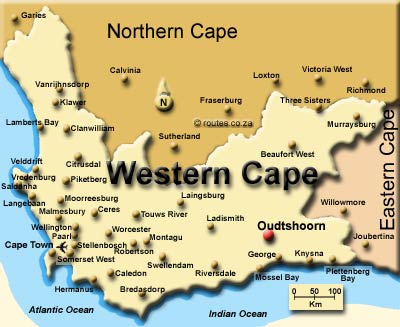

Oudtshoorn is located in the Klein (Little) Karoo, an arid region 350 kilometers east of Cape Town. The name Karoo was given to the area by its original San (Bushman) residents, who have left behind rock paintings in the nearby Swartberg mountains, much of which is now a UNESCO natural World Heritage Site. The Little Karoo is a fertile inland plateau wedged between the Swartberg in the north and Langeberg and Outeniqua mountains on the south. Oudtshoorn is the central town of the region.

The first known Europeans to reach the Little Karoo was a trading party led by a certain Ensign Shrijver, who were guided there by a Griqua via an ancient elephant trail in January 1689. However, the area was only settled a hundred years later as a farm named Hartenbeesrivier. The first large permanent structure, a Dutch Reformed Church, was first erected in 1839 near the banks of the Grobbelaars River on land donated by Cornelius Petrus Rademeyer. The town that gradually grew around this church, which was originally known as Veldschoendorp, was given the name Oudtshoorn by the Magistrate of George, in memory of the daughter of Baron Pieter van Rheede van Oudtshoorn, who was appointed Governor of the Cape Colony by the Dutch East India Company, but died aboard ship in 1772, before his arrival at Cape Town.

Nothing really happened over the following decades, though a small school was opened in 1858, followed by the formation of a municipality, the founding of an Agricultural Society and work on a larger church to replace the original. Unfortunately, in 1859 a long and serious drought commenced which severely depressed the South African economy leading to serious poverty. The drought was finally broken by floods in 1869. With the depression lifted, Oudtshoorn was transformed from a struggling village to a town of great prosperity over the following decades.

The first known Europeans to reach the Little Karoo was a trading party led by a certain Ensign Shrijver, who were guided there by a Griqua via an ancient elephant trail in January 1689. However, the area was only settled a hundred years later as a farm named Hartenbeesrivier. The first large permanent structure, a Dutch Reformed Church, was first erected in 1839 near the banks of the Grobbelaars River on land donated by Cornelius Petrus Rademeyer. The town that gradually grew around this church, which was originally known as Veldschoendorp, was given the name Oudtshoorn by the Magistrate of George, in memory of the daughter of Baron Pieter van Rheede van Oudtshoorn, who was appointed Governor of the Cape Colony by the Dutch East India Company, but died aboard ship in 1772, before his arrival at Cape Town.

Nothing really happened over the following decades, though a small school was opened in 1858, followed by the formation of a municipality, the founding of an Agricultural Society and work on a larger church to replace the original. Unfortunately, in 1859 a long and serious drought commenced which severely depressed the South African economy leading to serious poverty. The drought was finally broken by floods in 1869. With the depression lifted, Oudtshoorn was transformed from a struggling village to a town of great prosperity over the following decades.

San (Bushman) Rock Art in Swartberg

Map of Western Cape Province in South Africa

The Ostrich Booms

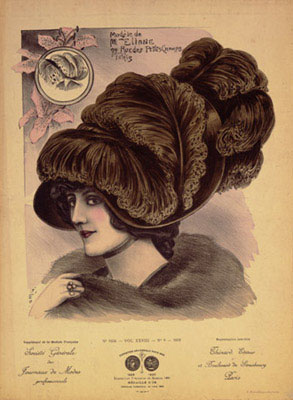

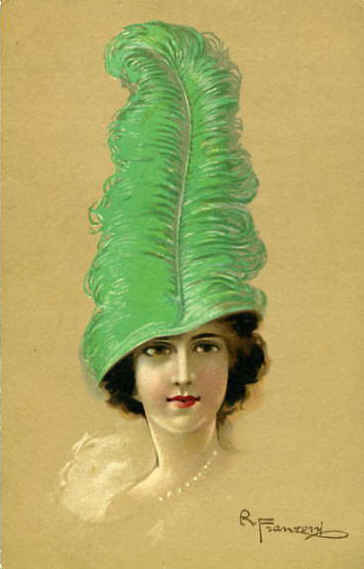

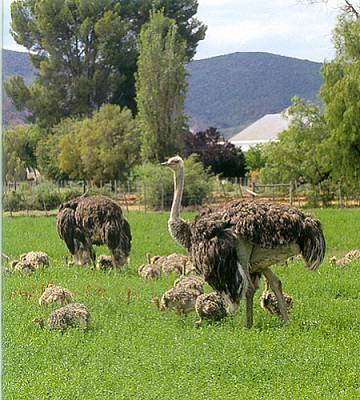

The main reason for Oudtshoorn’s quick fortune can be summed up in the unlikely form of the ostrich. The huge flightless bird, indigenous to Africa, and ideally suited to the Karoo’s dry environment, produced magnificent feathers that had become extremely popular as high fashion accessories in fin-de-siecle Britain and Europe, especially when feather trimming became de rigueur for hats and boas.

In 1821 the Cape of Good Hope exported 1230 kg of wild ostrich feathers valued at 115 590 rix-dollars. By 1858, although only 915 kg of feathers were exported, they were valued at twice the price. Seeing the potential, the farmers of the Oudtshoorn district pioneered the domestication of ostriches in the 1850's. Lucerne or alfalfa was introduced to South Africa and the birds thrived on the new diet. The Boer of Oudtshoorn immediately realising that farming ostriches were far more profitable than any other activity, ripped out their other crops and planted lucerne. The ostriches were placed in large fenced off areas and soon began breeding. The number of breeding birds rose from only 80 in 1865 to well over 20000 by 1875. Between 1875 and 1880 birds were selling for up to £1000 a pair.

The main reason for Oudtshoorn’s quick fortune can be summed up in the unlikely form of the ostrich. The huge flightless bird, indigenous to Africa, and ideally suited to the Karoo’s dry environment, produced magnificent feathers that had become extremely popular as high fashion accessories in fin-de-siecle Britain and Europe, especially when feather trimming became de rigueur for hats and boas.

In 1821 the Cape of Good Hope exported 1230 kg of wild ostrich feathers valued at 115 590 rix-dollars. By 1858, although only 915 kg of feathers were exported, they were valued at twice the price. Seeing the potential, the farmers of the Oudtshoorn district pioneered the domestication of ostriches in the 1850's. Lucerne or alfalfa was introduced to South Africa and the birds thrived on the new diet. The Boer of Oudtshoorn immediately realising that farming ostriches were far more profitable than any other activity, ripped out their other crops and planted lucerne. The ostriches were placed in large fenced off areas and soon began breeding. The number of breeding birds rose from only 80 in 1865 to well over 20000 by 1875. Between 1875 and 1880 birds were selling for up to £1000 a pair.

Early Houses in Oudtshoorn

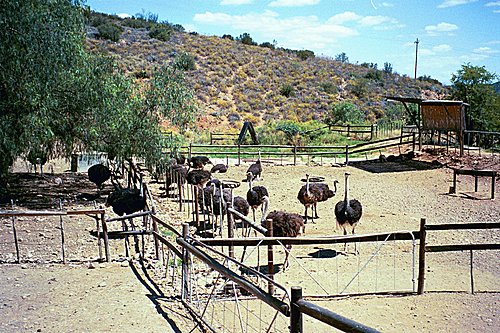

With a minimal amount of capital farmers planted lucerne, acquired pairs of breeding birds, incubators, a few sheds, some equipment and a primitive farmhouse. Most farmers gathered five plumages from the ostriches over a period of about five years. After the fifth plumage the quality of the feathers seemed to deteriorate significantly.

With so many new ostrich farmers, the supply of feathers grew resulting in a slight drop in the price. The larger

With so many new ostrich farmers, the supply of feathers grew resulting in a slight drop in the price. The larger

An Early Ostrich Farm in Oudtshoorn

farmers howeever were hardly affected because of the volumes they were producing and exporting. The best quality feathers still commanding high prices, over 200 rand per kilogramme in 1884 when the general price for lower quality plumage was only 6 rand per kg. By this time the ostrich feather industry had become a significant factor in the South African economy. After gold, diamonds and wool, the ostrich feather was the country's fourth largest export.

Ostrich Feather Hat Fashion in Victorian and Edwardian Europe

Prosperity, First Slump and the Jews Arrive

Around this time Lithuanian Jews who were looking for new economic opportunities started to arrive in Oudtshoorn to take part in the ostrich boom. They opened businesses trading in the valuable commodity and good relations were established between the Afrikaans speaking farmers and the Jewish immigrants.

The rising wealth allowed for the completion of the new Dutch Reformed Church on 7 June 1879, but prosperity led to overproduction and the ostrich industry experienced a sudden slump in 1885; compounded by severe flooding, which washed away the new Victoria Bridge which had been built over the nearby Olifants River. Still, in 1886, when the number of Jews was about 250, the decision was made to build a synagogue, sponsored in part by their Afrikaner neighbours.

The ostrich industry recovered slowly, and though Oudtshoorn had not been directly affected by the Second Anglo-Boer War of 1899 to 1902, the economic overspill meant the industry could only boom again at wars end. Incredible surplus wealth swamped the isolated town and in the first decade of the twentieth century most of Oudtshoorn's opulent 'Feather Palaces' were built (see below). At the high point of the feather trade some 300 Jewish families emigrated from Lithuania to the town, which was nicknamed the 'Jerusalem of South Africa'. Among these migrants was Max Rose, who arrived in 1890 and after ten years became the unrivalled feather baron in the whole of South Africa. The feather had become a major force in South Africa's economy.

The first indication of problems in the industry came in 1911 with signs of overproduction and increasing competition, especially from California. The South African ostrich breeders realised that the only way they could continue to dominate the world market was to produce the best feathers in the world. This led to the crossbreeding with the Barbary Ostrich to produce double-fluff feathers. 1913 brought a bumper crop of high quality feathers with the price of the finest double-fluff feathers reaching R 650 per kg earning the country about R 6 million. The ostrich feather industry would never reach these heights again.

Around this time Lithuanian Jews who were looking for new economic opportunities started to arrive in Oudtshoorn to take part in the ostrich boom. They opened businesses trading in the valuable commodity and good relations were established between the Afrikaans speaking farmers and the Jewish immigrants.

The rising wealth allowed for the completion of the new Dutch Reformed Church on 7 June 1879, but prosperity led to overproduction and the ostrich industry experienced a sudden slump in 1885; compounded by severe flooding, which washed away the new Victoria Bridge which had been built over the nearby Olifants River. Still, in 1886, when the number of Jews was about 250, the decision was made to build a synagogue, sponsored in part by their Afrikaner neighbours.

The ostrich industry recovered slowly, and though Oudtshoorn had not been directly affected by the Second Anglo-Boer War of 1899 to 1902, the economic overspill meant the industry could only boom again at wars end. Incredible surplus wealth swamped the isolated town and in the first decade of the twentieth century most of Oudtshoorn's opulent 'Feather Palaces' were built (see below). At the high point of the feather trade some 300 Jewish families emigrated from Lithuania to the town, which was nicknamed the 'Jerusalem of South Africa'. Among these migrants was Max Rose, who arrived in 1890 and after ten years became the unrivalled feather baron in the whole of South Africa. The feather had become a major force in South Africa's economy.

The first indication of problems in the industry came in 1911 with signs of overproduction and increasing competition, especially from California. The South African ostrich breeders realised that the only way they could continue to dominate the world market was to produce the best feathers in the world. This led to the crossbreeding with the Barbary Ostrich to produce double-fluff feathers. 1913 brought a bumper crop of high quality feathers with the price of the finest double-fluff feathers reaching R 650 per kg earning the country about R 6 million. The ostrich feather industry would never reach these heights again.

Dutch Reformed Church in Oudtshoorn - 1879

Oudsthoorn Coat of Arms

Originally belonged to the Dutch Oudsthoorn Family. Two Ostrich Plumes added for the Oudsthoorn Municipality Emblem

Originally belonged to the Dutch Oudsthoorn Family. Two Ostrich Plumes added for the Oudsthoorn Municipality Emblem

The Feather Market Collapses

1913, the very year the feather reached its highest price was the year that fashion started changing, due in part to the popularity of open motor cars, whose speed was not conducive to wearing clothes or hats adorned with feathers. The start of World War I put the final nail in the coffin. Both in South Africa and in London there were warehouses full of feathers, with no buyers. The feathers were worth next to nothing and the feather buyers were left with debts owed them by the dealers and therefore could not pay the farmers, who started growing tobacco and raising livestock to counter the effects of the collapse of the feather market. Farmers and feather buyers who had been millionaires one day found themselves poverty stricken the next, including the now bankrupt Gillis family. According to one story, an ostrich merchant framed two checks as a record of the speed with which he had been ruined. The first, a 1914 check for £100,000, his bank had honoured. The second, dated a year later for £1, had been refused.

At the end of the war there were still 314000 domesticated ostriches left in South Africa but by 1930 this number had declined to only 32000 and to 2000 in 1940.

1913, the very year the feather reached its highest price was the year that fashion started changing, due in part to the popularity of open motor cars, whose speed was not conducive to wearing clothes or hats adorned with feathers. The start of World War I put the final nail in the coffin. Both in South Africa and in London there were warehouses full of feathers, with no buyers. The feathers were worth next to nothing and the feather buyers were left with debts owed them by the dealers and therefore could not pay the farmers, who started growing tobacco and raising livestock to counter the effects of the collapse of the feather market. Farmers and feather buyers who had been millionaires one day found themselves poverty stricken the next, including the now bankrupt Gillis family. According to one story, an ostrich merchant framed two checks as a record of the speed with which he had been ruined. The first, a 1914 check for £100,000, his bank had honoured. The second, dated a year later for £1, had been refused.

At the end of the war there were still 314000 domesticated ostriches left in South Africa but by 1930 this number had declined to only 32000 and to 2000 in 1940.

Ostiches near Oudtshoorn

The conduct of a feather auction sale is very interesting. There are features about it different to ordinary auctions. For instance, a sale we attended was composed entirely of buyers. The feathers had been entrusted to the auctioneer as broker, and he represented most of the owners. Although the audience was most orderly, it was the keenest gathering imaginable. Jewish buyers in force, with a few slim farmers in opposition, and the cutest possible auctioneer in command. There were probably £8,000 worth of feathers for sale, so it was a fairly big sale. The first regulation read out was that there should be a reserve price on all feathers, and that they should be sold to the highest bidder above that price. The decision of the auctioneer was always to be final in case of dispute, and all sales were for spot cash (nobody trusts anybody in the feather business). The attendance at a sale can only be secured by the introduction of an auctioneer and broker, a compound avocation, and from a local bank, and any person, other than the owner or the buyer, who wishes to attend must first be properly introduced by the broker or a responsible buyer. There were only three English firms represented.

Most of the feathers in the district are sold out of hand, while they are on the bird- sometimes three months in advance. The broker whose sale we attended informed us that his sales averaged over £60,000 a year. The profits made by individual farmers are enormous. One farmer lately contracted to sell to a local buyer the whole of his stock of feathers representing the plucking of 2,000 ostriches, at £6 per bird. This was only one of several interests that he had. His tenants pay him £3,000 a year. Besides all this he has a large vineyard and orchard, and makes a lot of money out of dried fruit.

Most of the feathers in the district are sold out of hand, while they are on the bird- sometimes three months in advance. The broker whose sale we attended informed us that his sales averaged over £60,000 a year. The profits made by individual farmers are enormous. One farmer lately contracted to sell to a local buyer the whole of his stock of feathers representing the plucking of 2,000 ostriches, at £6 per bird. This was only one of several interests that he had. His tenants pay him £3,000 a year. Besides all this he has a large vineyard and orchard, and makes a lot of money out of dried fruit.

Auctioning Feathers

from "Cape Colony To-day Illustrated," A.R.E. Burton, 1907

from "Cape Colony To-day Illustrated," A.R.E. Burton, 1907

Afrikaans Culture

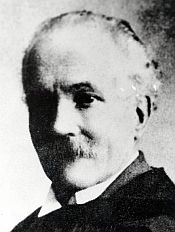

Oudtshoorn is one of the homes of Afrikaans language and culture. The towns most famous resident was Cornelis Jacobus Langenhoven (1873-1931), who is considered to be one of the fathers of Afrikaans. By 1914 he became a member of parliament, where he struggled to have Afrikaans officially recognised as a national language. He was a prodigious writer, authoring important Afrikaans literature and penning 'Die Stem van Suid-Afrika', the national anthem of South Africa prior to Nelson Mandela’s release and majority rule.

Langenhoven’s home, Arbeitsgenot, became a national monument. Following his cultural lead is South Africa's largest Afrikaans language arts festival, The Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees (Little Karoo National Arts Festival), that takes place annually in Oudtshoorn.

Oudtshoorn is one of the homes of Afrikaans language and culture. The towns most famous resident was Cornelis Jacobus Langenhoven (1873-1931), who is considered to be one of the fathers of Afrikaans. By 1914 he became a member of parliament, where he struggled to have Afrikaans officially recognised as a national language. He was a prodigious writer, authoring important Afrikaans literature and penning 'Die Stem van Suid-Afrika', the national anthem of South Africa prior to Nelson Mandela’s release and majority rule.

Langenhoven’s home, Arbeitsgenot, became a national monument. Following his cultural lead is South Africa's largest Afrikaans language arts festival, The Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees (Little Karoo National Arts Festival), that takes place annually in Oudtshoorn.

Langenhoven and Arbeitsgenot

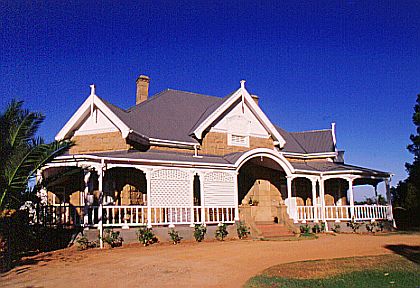

The Feather Palaces

The most visible remnants of Oudtshoorn's glory days are the crumbling architectural fantasias known as feather palaces. Amassed feather based wealth meant that the nouveau-riche of Oudtshoorn had the resources to invest in opulent homes.

The most visible remnants of Oudtshoorn's glory days are the crumbling architectural fantasias known as feather palaces. Amassed feather based wealth meant that the nouveau-riche of Oudtshoorn had the resources to invest in opulent homes.

Langenhoven and Arbeitsgenot

This was led by the arrival in 1903 of Charles Bullock, a British architect, who opened an office in the town. He was later joined in 1907 by a Dutch architect, Johannes Egbertus Vixeboxse. One of their first commissions from the Cape Superintendent of Education was a modern school building opened in 1907 on Baron van Rheede Street, formally Queens St. in the centre of the town.. This ornate building reflects a late Victorian Colonial style of a classical building. The 30m high tower is decorated with Corinthian ornaments, with octagonal "koepel" rounded off with a green wrought iron crown. On both sides of the central clock tower the facade is symmetrically designed. Both sides end with verandas bolstered by sandstone pillars in the Tuscany building style.

Over the years Bullock's firm and others would be responsible for a number of Oudtshoorn's famous ostrich palaces, all built in distinctive sandstone. The architecture, influenced by contemporary art-nouveau designs, was an unique eclectic mix using styles, methods and materials regardless of cost or even suitability. The resulting buildings were constructed with thick sandstone walls from local quarries, with corrugated - iron verandahs that almost encircle the houses, high ceilings, large sash windows with heavy wooden (teak!) shutters, decoration with white cast-iron lace-work brackets and railings, all contrasting the raw sandstone walls and red roofs. Quite something for a town in the middle of no-where.

The Boys High School, 1906

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

Post-Feather Oudtshoorn

Oudtshoorns foutunes declined with the loss of the feather market. The lucerne was replaced with fields of tobacco which became a major income earner for the rural farms and the town's factories. But poverty, the rise of Afrikaner nationalism and the influence of fascist ideologies in the thirties and forties would take a toll on the relationships between Afrikaner, Englishman and Jew, leading to an orchestrated campaign of arson against Jewish property during the years of World War II. After the war the ostrich trade slowly recovered and expanded from feathers to include skins, meat and a brand new source of income - tourism. Ostrich shows became tourist favourites together with the magnificent Cango stalactite caves near the town.

Almost every part of the ostrich is now utilised and ostrich leather is very popular in a variety of fashion items including shoes, clothes, handbags and most recently ostrich leather jewelry. Previously cheap ostrich meat steadily increased in price because of increasing consumption as a result of it's extremely low fat content and similarity to beef.

Oudtshoorn of today is a large town of 87000 people that relies mostly on tourism, farming and the ever-present ostrich industry for most of its economic activity. In fact, Oudtshoorn still has the world's largest population of ostriches with 200000 birds on 500 farms. Many farms and specialised breeding centres have been set up around the town and Oudtshoorn’s CP Nel Museum, located in the former Boy's High School, specialises in the history of the ostrich and the impact of ostrich farming on the town and its community. There is also a section of the museum devoted to the role of the Jewish community in the development of Oudtshoorn's feather industry including the reconstructed Aron HaKodesh from the now demolished Johns St. Greener Synagogue.

Oudtshoorns foutunes declined with the loss of the feather market. The lucerne was replaced with fields of tobacco which became a major income earner for the rural farms and the town's factories. But poverty, the rise of Afrikaner nationalism and the influence of fascist ideologies in the thirties and forties would take a toll on the relationships between Afrikaner, Englishman and Jew, leading to an orchestrated campaign of arson against Jewish property during the years of World War II. After the war the ostrich trade slowly recovered and expanded from feathers to include skins, meat and a brand new source of income - tourism. Ostrich shows became tourist favourites together with the magnificent Cango stalactite caves near the town.

Almost every part of the ostrich is now utilised and ostrich leather is very popular in a variety of fashion items including shoes, clothes, handbags and most recently ostrich leather jewelry. Previously cheap ostrich meat steadily increased in price because of increasing consumption as a result of it's extremely low fat content and similarity to beef.

Oudtshoorn of today is a large town of 87000 people that relies mostly on tourism, farming and the ever-present ostrich industry for most of its economic activity. In fact, Oudtshoorn still has the world's largest population of ostriches with 200000 birds on 500 farms. Many farms and specialised breeding centres have been set up around the town and Oudtshoorn’s CP Nel Museum, located in the former Boy's High School, specialises in the history of the ostrich and the impact of ostrich farming on the town and its community. There is also a section of the museum devoted to the role of the Jewish community in the development of Oudtshoorn's feather industry including the reconstructed Aron HaKodesh from the now demolished Johns St. Greener Synagogue.

Jewish Cemetery

GILLIS ST.

Gillis Houses

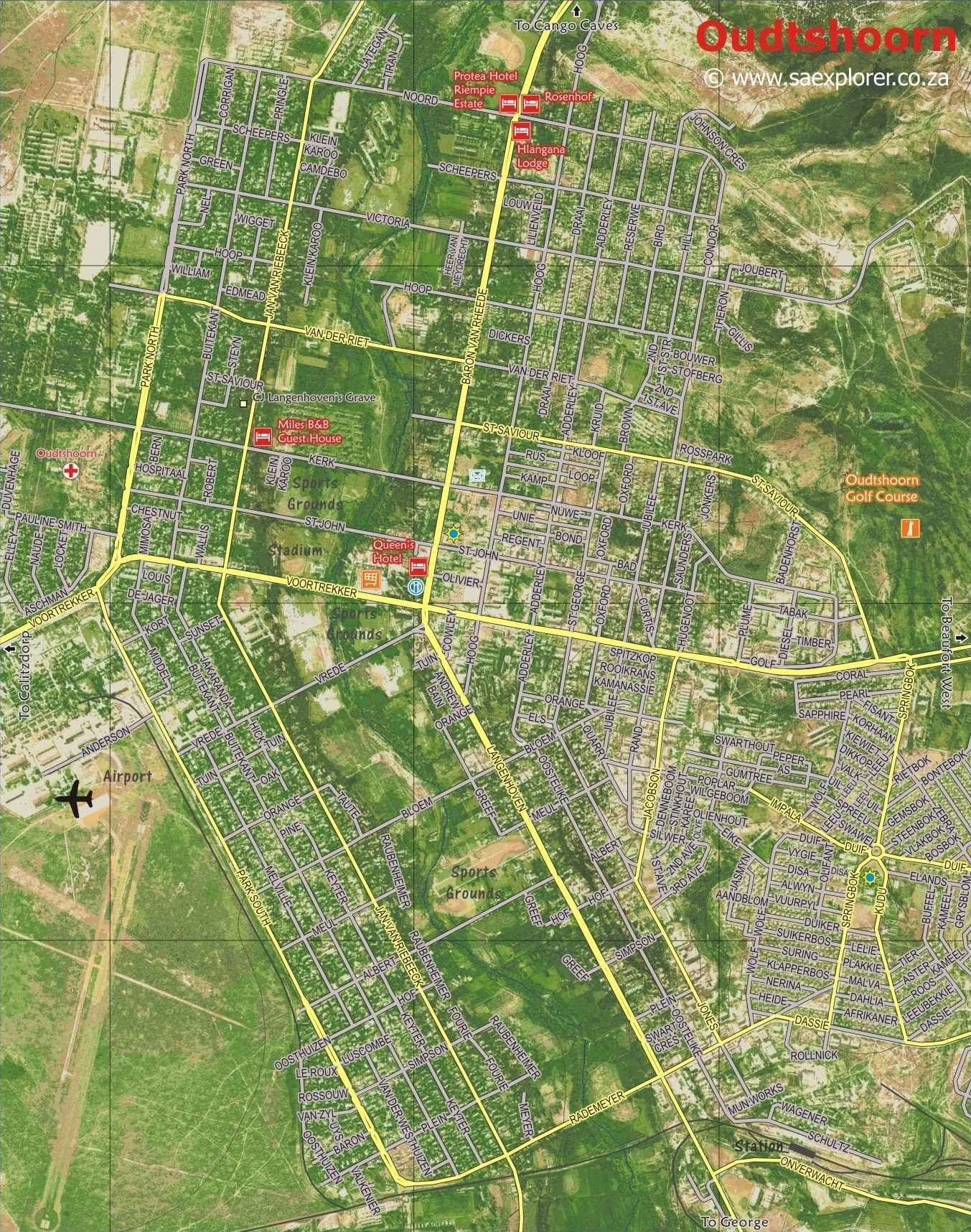

Maps and Satallite Image of Oudtshoorn.

Note Gillis St. near golf course probably named after Bennie Gillis who was Mayor of the town for three years

Note Gillis St. near golf course probably named after Bennie Gillis who was Mayor of the town for three years

Thumbnail Images of Oudtshoorn and the Klein Karoo

The Cango Caves

The Klein (Little) Karoo

Ostrich Farming and Feathers

Scenes from Oudtshoorn

Copyright © 2007 Jon Seligman. All Rights Reserved.