Jerusalem of South Africa

Jewish Community

33°35'S 22°12'E

Oudtshoorn - The Jewish Community

Oudtshoorn is one of South Africa’s most interesting Jewish historic centres. So vibrant was the Jewish community that the town was named, with some degree of exaggeration, 'Little Jerusalem' or 'Yerushalayim beDerom Afrika' (Jerusalem of South Africa).

The community grew up in a short space of time around the trading of ostrich feathers, as prices for the feathers soared and Jews flocked to the isolated little town in the Klein Karoo to join in the prosperity. In fact two waves of Jewish immigrants arrived in the town from the mid-19th century to the first decade of the 20th century. The first arrived as part of Sir George Grey’s immigration scheme from 1858 to 1861, during which large groups of people of German origin settled in the Cape together with skilled tradesmen from the British Isles. The second wave consisted of Jews from Latvia and Lithuania who came to escape the mobilisation of many young Jews to the Russian army between 1881 and 1910 and the anti-semitism that limited their ability to lead productive lives. Most fled to Britain, where they regrouped and moved on the USA or to the colonies of the British Empire. Some, on reaching Cape Town, would have been told of the fortunes to be made in Oudtshoorn and then moved there, started businesses dealing in ostrich feathers.

The community grew up in a short space of time around the trading of ostrich feathers, as prices for the feathers soared and Jews flocked to the isolated little town in the Klein Karoo to join in the prosperity. In fact two waves of Jewish immigrants arrived in the town from the mid-19th century to the first decade of the 20th century. The first arrived as part of Sir George Grey’s immigration scheme from 1858 to 1861, during which large groups of people of German origin settled in the Cape together with skilled tradesmen from the British Isles. The second wave consisted of Jews from Latvia and Lithuania who came to escape the mobilisation of many young Jews to the Russian army between 1881 and 1910 and the anti-semitism that limited their ability to lead productive lives. Most fled to Britain, where they regrouped and moved on the USA or to the colonies of the British Empire. Some, on reaching Cape Town, would have been told of the fortunes to be made in Oudtshoorn and then moved there, started businesses dealing in ostrich feathers.

The Queen Street Synagogue - Der Englishe Shul

At first religious ceremonies were held in private houses and in the feather market hall of the town council. By 1886, when the number of Jews was about 250, the decision was made, with the encouragement of Rabbi Orenstein of Cape Town, to build a synagogue.

The Afrikaner boers and the Jews were both deeply religious people and a bond developed between them. Indeed, the Afrikaners were in awe and the minister of the local church said in his sermon: "What a glorious thing it would be to have the children of the Old Testament worshipping in our midst." One of the Afrikaners donated two plots for the synagogue, while another donated the stones and had them brought to the site. Architectural plans were drawn up by the architect George Wallis and approved. The building commenced on 26 January 1888, Rabbi Orenstein laid the foundation stone and by December the synagogue was inaugurated.

At first religious ceremonies were held in private houses and in the feather market hall of the town council. By 1886, when the number of Jews was about 250, the decision was made, with the encouragement of Rabbi Orenstein of Cape Town, to build a synagogue.

The Afrikaner boers and the Jews were both deeply religious people and a bond developed between them. Indeed, the Afrikaners were in awe and the minister of the local church said in his sermon: "What a glorious thing it would be to have the children of the Old Testament worshipping in our midst." One of the Afrikaners donated two plots for the synagogue, while another donated the stones and had them brought to the site. Architectural plans were drawn up by the architect George Wallis and approved. The building commenced on 26 January 1888, Rabbi Orenstein laid the foundation stone and by December the synagogue was inaugurated.

The Englishe Shul - 1888

In the year of the opening of the synagogue Rabbi Wolfson arrived in the Cape Colony to take up duties in the Transvaal town of Barberton but instead he took up the position of Rabbi in Oudtshoorn, where he served the community for over fifty years from the pulpit of what would be eventually known as the Englische Shul.

Finding Parnosa

The newcomers were engaged in the marketing and ultimately in the production of ostrich feathers, illustrating the misconception that Jews were not only the middlemen engaged in the sale of the ostrich feathers but also active farmers in the district. Still, of the 50 Jews in Oudtshoorn who were naturalized as citizens of the Cape Province between 1883 and 1890, 37 gave their occupation as "feather buyer" and two others were feather sorters. Many of the buyers walked from farm to farm, carrying their feathers in a bag slung over their backs. By 1910 there were 277 licensed feather buyers in the area, almost all of them Jews. The Jews who settled in the farming areas learned only Afrikaans, though English was spoken in the town, where it was learned from the British settlers, many of whom were shopkeepers.

The newcomers were engaged in the marketing and ultimately in the production of ostrich feathers, illustrating the misconception that Jews were not only the middlemen engaged in the sale of the ostrich feathers but also active farmers in the district. Still, of the 50 Jews in Oudtshoorn who were naturalized as citizens of the Cape Province between 1883 and 1890, 37 gave their occupation as "feather buyer" and two others were feather sorters. Many of the buyers walked from farm to farm, carrying their feathers in a bag slung over their backs. By 1910 there were 277 licensed feather buyers in the area, almost all of them Jews. The Jews who settled in the farming areas learned only Afrikaans, though English was spoken in the town, where it was learned from the British settlers, many of whom were shopkeepers.

As the Jewish population increased, so did the scope of their activities, with many becoming traders or smouses, itinerant dealers traveling between the farms with a horse and cart, selling all kinds of household wares to the farmers. They also became shopkeepers and hoteliers in the town.

A Synagogue to Pray In and a Synagogue to Never Visit

Many of the Litvaks who settled in Oudsthoorn came from two adjacent shtetls, Kelme and Shavel (Shavli or Siauliai). Soon however the two community groups, the orthodox Mitnagdim of Kelme and the more liberal Jews from urban Shavel could not see eye-to-eye about how to conduct ceremonies and relate to tradition within the framework of a single synagogue. The Queen St. synagogue operated only on Shabbat and Yom Tov and did not provide study facilities.The Kelme Jews felt that Rabbi Wolfson was overly influenced by German and English religious practice and wished for daily service and the formation of a Beit Midrash.

In 1892 the Kelme Jews split from the community and built a second synagogue on St. Johns Street, nicknamed the ‘Griener Shul’ in which they strove to re-create the atmosphere of their beloved home town synagogue and graft it into the Karoo. The result was a copy of a Lithuanian heimland synagogue decorated with original Lithuanian-style Jewish handicraft, silver work and embroidery. After the dismantling of this community in 1973 the contents, including the magnificent onion domed ark, which had been modeled on the ark in the synagogue in Kelme, were moved to the Nel museum where it remains on display.

Many of the Litvaks who settled in Oudsthoorn came from two adjacent shtetls, Kelme and Shavel (Shavli or Siauliai). Soon however the two community groups, the orthodox Mitnagdim of Kelme and the more liberal Jews from urban Shavel could not see eye-to-eye about how to conduct ceremonies and relate to tradition within the framework of a single synagogue. The Queen St. synagogue operated only on Shabbat and Yom Tov and did not provide study facilities.The Kelme Jews felt that Rabbi Wolfson was overly influenced by German and English religious practice and wished for daily service and the formation of a Beit Midrash.

In 1892 the Kelme Jews split from the community and built a second synagogue on St. Johns Street, nicknamed the ‘Griener Shul’ in which they strove to re-create the atmosphere of their beloved home town synagogue and graft it into the Karoo. The result was a copy of a Lithuanian heimland synagogue decorated with original Lithuanian-style Jewish handicraft, silver work and embroidery. After the dismantling of this community in 1973 the contents, including the magnificent onion domed ark, which had been modeled on the ark in the synagogue in Kelme, were moved to the Nel museum where it remains on display.

According to one story the reason for the building of the second synagogue in the town was even more controversial.

"Reverend Wolfson, while reading from the Torah at services, objected to anybody in Shul singing together with him. There was one congregant who persisted in this practice despite being told by Reverend Wolfson to stop doing this. The Reverend, a very short-tempered individual, strode from the Bimah and slapped him in the face. The frum Kelme Jews considered this action as insulting to Jewish tradition and decided to establish their own Shul."

The Legend of the Slap

from Oudtshoorn - "Yerusholayim b'Dorem Afrika", Bertha Widan, SA-SIG Newsletter, Vol.4:2, 2003

from Oudtshoorn - "Yerusholayim b'Dorem Afrika", Bertha Widan, SA-SIG Newsletter, Vol.4:2, 2003

The Jewish Community and the Development of Oudtshoorn

The Jews were intimately involved in the growth of ostrich farming as farmers and traders. With their growing prosperity Jewish farmers, merchants and buyers started to build showpiece sandstone manor houses known as ‘Feather Palaces’. Some Jews diversified their business into the tobacco trade, including the Gillises, while others adopted the professions, especially as doctors, dentists and lawyers.

Education as always was seen as an essential. Sons and daughters of the community were sent both to the large cities and abroad to qualify in the professions, while in 1904 Oudtshoorn established the first Jewish government school ever in South Africa. This primary school gave a general education together with daily Hebrew classes as part of the syllabus.

The most important breeder and trader of ostriches in Oudtshoorn was a certain Max Rose, known as as the ostrich feather king. He arrived in 1890 from Shavel and quickly developed his business. In 1906 he bought the Weltevreden farm near Ladismith for 18000 pounds. The same farm was sold in 1913 for 200000 pounds, though after the collapse of the market it was worth no more than 15000.

The Jews were intimately involved in the growth of ostrich farming as farmers and traders. With their growing prosperity Jewish farmers, merchants and buyers started to build showpiece sandstone manor houses known as ‘Feather Palaces’. Some Jews diversified their business into the tobacco trade, including the Gillises, while others adopted the professions, especially as doctors, dentists and lawyers.

Education as always was seen as an essential. Sons and daughters of the community were sent both to the large cities and abroad to qualify in the professions, while in 1904 Oudtshoorn established the first Jewish government school ever in South Africa. This primary school gave a general education together with daily Hebrew classes as part of the syllabus.

The most important breeder and trader of ostriches in Oudtshoorn was a certain Max Rose, known as as the ostrich feather king. He arrived in 1890 from Shavel and quickly developed his business. In 1906 he bought the Weltevreden farm near Ladismith for 18000 pounds. The same farm was sold in 1913 for 200000 pounds, though after the collapse of the market it was worth no more than 15000.

The Ark of the Griener Shul

Today in CP Nel Museum in Oudtshoorn on the initiative of Bernard Medintz.

Today in CP Nel Museum in Oudtshoorn on the initiative of Bernard Medintz.

Even though he had sold up in time, Rose lost heavily when the ostrich feather became unfashionable. Still he commanded respect and the government commissioned him to write a report for the recovery of the market. Though his recommendations, including the establishment of a central feather market, were adopted by government, the former wealth generated by the ostrich industry became illusive.

Other Jews also became central figures in the general Oudtshoorn community. At one stage, the mayor and two of the councilors were Jewish, as was the district surgeon, the medical officer of health and a member of the municipal school board. In 1899 Moritz Aschman was elected to the municipal council, serving on the School and Hospital Boards and for several years was he was the president of the Jewish Philanthropic Society. Arthur Jacobson opened a law office in the town in 1893. In 1903 he was appointed Justice of the Peace for Oudtshoorn and in 1914 he was the first Jew to become Mayor of Oudtshoorn.

Other Jews also became central figures in the general Oudtshoorn community. At one stage, the mayor and two of the councilors were Jewish, as was the district surgeon, the medical officer of health and a member of the municipal school board. In 1899 Moritz Aschman was elected to the municipal council, serving on the School and Hospital Boards and for several years was he was the president of the Jewish Philanthropic Society. Arthur Jacobson opened a law office in the town in 1893. In 1903 he was appointed Justice of the Peace for Oudtshoorn and in 1914 he was the first Jew to become Mayor of Oudtshoorn.

Between Calitzdorp and Oudtshoorn was a 30 mile stretch of road known as Der Yiddishe Gass, owing to the fact that all the shops and one hotel along the road were Jewish owned. Not all the shops had doors, so the customers used to enter through the windows.

The Jewish inhabitants of the Gass were pious. Shabbat was strictly observed, the Gass resembling a Litvak shtetl, with the aroma of cholent and the sounds of Zmirot.

The Jewish inhabitants of the Gass were pious. Shabbat was strictly observed, the Gass resembling a Litvak shtetl, with the aroma of cholent and the sounds of Zmirot.

Der Yiddishe Gass

According to Coetzee, their presence met a mixed response. Commercial uncertainty, especially speculation of ostrich feathers, led to the age-old portrayal of Jews as userers. Still most contact with the Boers was positive. Smouses (peddlers) supplied goods to isolated farms and friendships developed between Jews and Afrikaners. The issue of language would play a decisive role in the relationship between Jews and their mainly Afrikaner neighbours. Would English or Afrikaans become the language of choice for communication, education and as the spoken tongue at home? Though most Jews learnt Afrikaans, most began to use English. English, was a symbol of middle class status and was considered to be the 'proper' language for the 'town' Jews who wished to be associated with the English businessmen who lived in the town. This and the community’s pro-British attitudes led many to side with Britain during the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902, even though many Afrikaners viewed the British as occupiers.

Oudtshoorn’s Jews steadily integrated into the white community, becoming deeply involved in civic affairs, though politically the town became polarised between the exclusively anti-British, rural Afrikaners who supported the National Party and pro-British Afrikaners, English and most Jews who aligned themselves with Louis Botha’s and Jan Smut’s South African Party (United Party), a pattern strengthened through Smuts’ affinity with Zionism.

Oudtshoorn’s Jews steadily integrated into the white community, becoming deeply involved in civic affairs, though politically the town became polarised between the exclusively anti-British, rural Afrikaners who supported the National Party and pro-British Afrikaners, English and most Jews who aligned themselves with Louis Botha’s and Jan Smut’s South African Party (United Party), a pattern strengthened through Smuts’ affinity with Zionism.

The Feather Collapse, Tobacco, Cooperatives and the Rise of Anti-Semitism

The Jewish population of Oudtshoorn grew with the growth of the Ostrich industry, peaking in 1914 with 600 families. The disintegration of the feather industry cost many their businesses. People were declared bankrupt, and both farmers and traders sold out for whatever they could recoup. With limited opportunities in other economic sectors, Jews started to drift away to the large cities of South Africa, half of the Jewish population moving by the end of World War I.

The economic effect would sour connections between many Jewish retailers or creditors and their Gentile customers or partners. Jews were accused of cheating the Afrikaners, who in turn responded by forming powerful cooperatives that cut out the dealers of feathers and tobacco. Slowly the economy of the town recovered. The well off Jews lived mostly in Queen St., close to the synagogue, while the poorer lived in St John, High and Adderley Streets. By the 30s the city had tobacco, leather, furniture and lucerne meal milling factories that employed thousands, many of these Jewish owned. This, together with the departure of Jews who had failed to make a living in Oudtshoorn, left an impression on the often poor rural Afrikaner population of themselves facing successful anglicized Jewish town shopkeepers and creditors.

Even Langenhoven, the MP for Oudtshoorn and an important proponent of Afrikaans, who usually retained friendly relations with the Jewish community, blamed the “parasitic Uitlander” for the “backwardness” of the “poor down trodden Afrikaner”. Langenhoven, like many of the extreme nationalist Afrikaners, would publicly attack the Jews as a community while maintaining friendships with local Jews as individuals. After all, Jews were an essential part of the economy with Jewish middlemen moving the produce from the farms to market and Jewish shops supplying the farmers and providing them credit between harvests. In all it seems that anti-Semitism in Oudtshoorn was triggered by fears of Jewish hegemony, not by the presence of Jewish individuals in the community. Political power moved to the boards of Afrikaner dominated agricultural cooperatives. Thus the Tobacco Cooperative’s executive was purely Afrikaner and led by le Roux, the local National Party leader. The cooperatives were resented by Oudtshoorn Jews for taking business away from them, and tobacco factory owners who were dependent on local tobacco, were especially troubled. For example, legislation in 1926 for a 100% wage increase in the tobacco industry suspiciously applied only to the Oudtshoorn district. In 1930 a Tobacco Cooperation Act, proposed in Parliament by le Roux, prevented independent farmers from dealing directly with factories, limited planting to increase prices and stopped even the delivery of tobacco from planters own fields to the factories of their family members. Two years later, Morris Gillis, a member of the tobacco co-op, was taken to court by the cooperative for selling to Gillis Brothers tobacco manufacturers without the consent of the cooperative.

Still not all was dark. Many Afrikaners had good contacts with Jewish families dating back to the feather days, with themes of friendship, charity, hospitality, mutual benefit, and only occasional friction. In the rural areas were also groups of so-called ‘Boerejode’, Jews who worked on the farms, and chose Afrikaans language and culture as their own. Many Jews’ Afrikaans accent was so good that it was impossible for an outsider to distinguish and some took an active role in the promotion of Afrikaans culture and language.

The Jewish population of Oudtshoorn grew with the growth of the Ostrich industry, peaking in 1914 with 600 families. The disintegration of the feather industry cost many their businesses. People were declared bankrupt, and both farmers and traders sold out for whatever they could recoup. With limited opportunities in other economic sectors, Jews started to drift away to the large cities of South Africa, half of the Jewish population moving by the end of World War I.

The economic effect would sour connections between many Jewish retailers or creditors and their Gentile customers or partners. Jews were accused of cheating the Afrikaners, who in turn responded by forming powerful cooperatives that cut out the dealers of feathers and tobacco. Slowly the economy of the town recovered. The well off Jews lived mostly in Queen St., close to the synagogue, while the poorer lived in St John, High and Adderley Streets. By the 30s the city had tobacco, leather, furniture and lucerne meal milling factories that employed thousands, many of these Jewish owned. This, together with the departure of Jews who had failed to make a living in Oudtshoorn, left an impression on the often poor rural Afrikaner population of themselves facing successful anglicized Jewish town shopkeepers and creditors.

Even Langenhoven, the MP for Oudtshoorn and an important proponent of Afrikaans, who usually retained friendly relations with the Jewish community, blamed the “parasitic Uitlander” for the “backwardness” of the “poor down trodden Afrikaner”. Langenhoven, like many of the extreme nationalist Afrikaners, would publicly attack the Jews as a community while maintaining friendships with local Jews as individuals. After all, Jews were an essential part of the economy with Jewish middlemen moving the produce from the farms to market and Jewish shops supplying the farmers and providing them credit between harvests. In all it seems that anti-Semitism in Oudtshoorn was triggered by fears of Jewish hegemony, not by the presence of Jewish individuals in the community. Political power moved to the boards of Afrikaner dominated agricultural cooperatives. Thus the Tobacco Cooperative’s executive was purely Afrikaner and led by le Roux, the local National Party leader. The cooperatives were resented by Oudtshoorn Jews for taking business away from them, and tobacco factory owners who were dependent on local tobacco, were especially troubled. For example, legislation in 1926 for a 100% wage increase in the tobacco industry suspiciously applied only to the Oudtshoorn district. In 1930 a Tobacco Cooperation Act, proposed in Parliament by le Roux, prevented independent farmers from dealing directly with factories, limited planting to increase prices and stopped even the delivery of tobacco from planters own fields to the factories of their family members. Two years later, Morris Gillis, a member of the tobacco co-op, was taken to court by the cooperative for selling to Gillis Brothers tobacco manufacturers without the consent of the cooperative.

Still not all was dark. Many Afrikaners had good contacts with Jewish families dating back to the feather days, with themes of friendship, charity, hospitality, mutual benefit, and only occasional friction. In the rural areas were also groups of so-called ‘Boerejode’, Jews who worked on the farms, and chose Afrikaans language and culture as their own. Many Jews’ Afrikaans accent was so good that it was impossible for an outsider to distinguish and some took an active role in the promotion of Afrikaans culture and language.

War and Arson

Jews continued to be elected to municipal power, and Bennie Gillis became the town’s third Jewish mayor in 1937, after two terms as deputy mayor, serving for a total of 25 years on the town council. This illustrated the place of Jews in society even with National Party hegemony of the political debate.

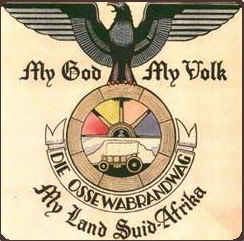

However, the influence of Nazi ideas led to the establishment of anti-Semitic Afrikaner movements known as the Grey and Black shirts and later to the endorsement of ‘volk’ based ideology around the celebrations of the centenary of the ‘Great Trek’ in 1938. This led to the founding of the ostensibly cultural Ossewabrandwag (Ox Wagon Sentinels) who adopted imagery and methods similar to those of fascist organisations in Europe. Even though these organisations became particularly vocal, especially with outbreak of war, their influence remained marginal in numerical terms. But violent action led by the few can still have impact and because of political unrest, Smuts placed Oudtshoorn under Emergency Law with the declaration of war

Jews continued to be elected to municipal power, and Bennie Gillis became the town’s third Jewish mayor in 1937, after two terms as deputy mayor, serving for a total of 25 years on the town council. This illustrated the place of Jews in society even with National Party hegemony of the political debate.

However, the influence of Nazi ideas led to the establishment of anti-Semitic Afrikaner movements known as the Grey and Black shirts and later to the endorsement of ‘volk’ based ideology around the celebrations of the centenary of the ‘Great Trek’ in 1938. This led to the founding of the ostensibly cultural Ossewabrandwag (Ox Wagon Sentinels) who adopted imagery and methods similar to those of fascist organisations in Europe. Even though these organisations became particularly vocal, especially with outbreak of war, their influence remained marginal in numerical terms. But violent action led by the few can still have impact and because of political unrest, Smuts placed Oudtshoorn under Emergency Law with the declaration of war

The Fading of the Oudtshoorn Jewish Community

The collapse of the Ostrich industry had been the first blow to the Jewish community, but the events of the war years and sociological changes within the community itself would reduce the numbers to little more than a minyan by the end of the twentieth century. War's end slowly brought calm, but the community never fully recovered from the impact of the arson attacks, the inaction of the local police and the breaking of mutual trust. Post-war Afrikaner sucess in placing Afrikaners in controlling positions in businesses and organisations grew, but still Jewish businesses remained in Oudtshoorn for decades. Community numbers quickly decreased, the principal driving force for leaving being upward mobility and urbanisation, leading to the move of most to the large cities of South Africa, and even abroad.

By 1955 there were only 150 families left and in 1973 the St. Johns St. Synagogue was closed. The ark and front pews were transferred to the local museum. Today only 17 families remain, five of whom are ostrich farmers, with community life still centred around the Queens St. (now Baron van Reede St.) Synagogue.

The collapse of the Ostrich industry had been the first blow to the Jewish community, but the events of the war years and sociological changes within the community itself would reduce the numbers to little more than a minyan by the end of the twentieth century. War's end slowly brought calm, but the community never fully recovered from the impact of the arson attacks, the inaction of the local police and the breaking of mutual trust. Post-war Afrikaner sucess in placing Afrikaners in controlling positions in businesses and organisations grew, but still Jewish businesses remained in Oudtshoorn for decades. Community numbers quickly decreased, the principal driving force for leaving being upward mobility and urbanisation, leading to the move of most to the large cities of South Africa, and even abroad.

By 1955 there were only 150 families left and in 1973 the St. Johns St. Synagogue was closed. The ark and front pews were transferred to the local museum. Today only 17 families remain, five of whom are ostrich farmers, with community life still centred around the Queens St. (now Baron van Reede St.) Synagogue.

Symbol of the Osswabrandwag

on Germany. During the war years large crowds saw local troops off (including many Jews), while Afrikaner nationalists, mainly members of Ossewabrandwag, celebrated the fall of Paris, refused to stand God Save the King in cinemas (which led to fights), threw stones at Jewish businesses and daubed the walls with swastikas. Though Jews were not physically attacked their businesses were targeted for an organised campaign of arson. From 1940 till 1947 a series of fires were set, destroying furniture and tobacco factories, shops in central Oudtshoorn, and after Bennie Gillis won a municipal seat in 1944, the Gillis Brothers tobacco factory was also lost to arson. During these assaults, the fire brigade would often arrive late, find that their equipment was faulty or rendered inoperable prior to the incident. In addition, Jewish farms were attacked, the livestock poisoned and the cemetery was desecrated. Though no culprits for these crimes was ever brought to justice the finger must point to members of the Ossewabrandwag, National Party and the cooperative movement.

RED LETTER DAY FOR OUDTSHOORN

Tears, Laughter and “Do you remember?” were the order of the day when 160 “Emigres” converged on Oudtshoorn for the centenary of the founding of its Jewish community. A full programme of cultural and religious functions did not deter informal celebratory gatherings that kept talk flowing till the small hours of the morning. One hundred years ago their forefathers had made their way to this little town “Der KleinerYerushalayim Bedorm Afrika”, where they founded a community rich in Jewish tradition and culture which has survived many decades.

The invitations to this celebration engendered such excitement that plans had to be expanded to cope with the anticipated influx. Then the Mayor and Town Council expressed their desire to pay tribute to the Jewish community in the form of a Civic Banquet where the Afrikaans community volunteered to do all the waiter and waitress duties.

Many dignitaries and their wives traveled to Oudtshoorn for the occasion: Rabbi Professor E. J. Duschinsky, Av Beth Din; Mr. Eliyahu Lankin, Ambassador for Israel; Mr. Mervyn Smith, Chairman Board of Deputies; and Mr. Barney Singer of the Western Province Zionist Council. On Thursday afternoon, the Mayoress, Mrs. D. de Jager, opened an exhibition, organised by Mrs. Bex Kroll, of Jewish cultural and historical items and memorabilia in the C.P. Nel Museum of part of the original St. John Street Shul. A most moving Erev Shabbat Shul service, augmented by the singing of Cantor Michael Cohen and the Claremont Shul Choir, was followed by an Oneg Shabbat at the adjoining Jewish Club. The star of the evening was Cantor Immerman who had served the community as both Cantor and teacher from 1927 to 1942. Past Barmitzvah pupils one by one stood up and identified themselves. Unhesitatingly Cantor Immerman, born blind, affectionately known as “Der Blinder Chazan”, recalled the dates of their barmitzvahs 40 to 60 years ago and the names of their Maftirs. To end the evening Madame Mabella Ott Paneto, the famous singer, originally Mabel Lewin of Oudtshoorn, who had flown in from Switzerland for the occasion came forward with a song called “Memories” which she had composed herself.

The Shabbat morning Shul service was a trip down Memory Lane. Shacharit was davened by Cantor Immerman, and Maftir was done by his ex-pupil Joe Batzofin, who had first sung it 49 years years ago as a Barmitzvah boy. The formal banquet for over 500 guests on the Saturday evening was a grand gesture of the mutual respect of Afrikaner and Jew. Kosher, down to the hiring and transport of crockery and cutlery from Cape Town, it began with Hamotzi. As mentioned earlier, this function was paid for by the Town Council.

Highlights of the memorable evening included an address by Minister Pik Botha, a response in flawless Afrikaans by Mervyn Smith, a Toast by the Mayor, Councillor A. J. de Jager, and the presentation on behalf of the Municipality of a magnificent Parochet (Aron Kodesh curtain). Ex Mayor, 94 Year old Mr. Bennie Gillis, proposed a toast to the State President. A special Thanksgiving Service on the Sunday morning in Shul was graced by the presence of government and local dignitaries and a sermon by Rabbi Duschinsky, who ended his sermon with the following words: “The characteristic of this unique community may be found in the fact that almost all of its present members are direct descendants of the original Jewish community. Many of the former residents left for other parts of the country, Israel, and the world at large, the remaining families all continued with the unchanged confluence of their own heritage flowing from the rivers of genuine Lithuanian Jewish traditions and western culture. The old cemetery, kept in dignity to this day, contains epitaphs of the old founders in classical Hebrew conveying the love for Zion, for the holy language, for all that is eternal in Jewish spiritual life.” A sudden shower as people emerged from the Shul was taken as a good omen even though it meant a quick switch of plans from a garden party at the Mayor’s residence next door, to the inside of the house. What can one say at the end of an unforgettable nostalgic trip down memory lane in the presence of the descendants of the second oldest Jewish Community in South Africa but to wish the Oudtshoorn Jewish Community everything of the best for the future.

In my own humble opinion the real reason which moved the early Jews to Oudtshoorn was that here was a place where they could keep the Shabbat in freedom in the manner their fathers had taught them. They came, originally, from Eastern Europe where their lives had been a succession of pogroms. Even in their struggle for survival they were never prepared to compromise their Jewish identity and they maintained their culture, traditions and religion throughout their lives. In conclusion I may mention that that spirit even prevails today in a community numbering seventeen Jewish families.

Tears, Laughter and “Do you remember?” were the order of the day when 160 “Emigres” converged on Oudtshoorn for the centenary of the founding of its Jewish community. A full programme of cultural and religious functions did not deter informal celebratory gatherings that kept talk flowing till the small hours of the morning. One hundred years ago their forefathers had made their way to this little town “Der KleinerYerushalayim Bedorm Afrika”, where they founded a community rich in Jewish tradition and culture which has survived many decades.

The invitations to this celebration engendered such excitement that plans had to be expanded to cope with the anticipated influx. Then the Mayor and Town Council expressed their desire to pay tribute to the Jewish community in the form of a Civic Banquet where the Afrikaans community volunteered to do all the waiter and waitress duties.

Many dignitaries and their wives traveled to Oudtshoorn for the occasion: Rabbi Professor E. J. Duschinsky, Av Beth Din; Mr. Eliyahu Lankin, Ambassador for Israel; Mr. Mervyn Smith, Chairman Board of Deputies; and Mr. Barney Singer of the Western Province Zionist Council. On Thursday afternoon, the Mayoress, Mrs. D. de Jager, opened an exhibition, organised by Mrs. Bex Kroll, of Jewish cultural and historical items and memorabilia in the C.P. Nel Museum of part of the original St. John Street Shul. A most moving Erev Shabbat Shul service, augmented by the singing of Cantor Michael Cohen and the Claremont Shul Choir, was followed by an Oneg Shabbat at the adjoining Jewish Club. The star of the evening was Cantor Immerman who had served the community as both Cantor and teacher from 1927 to 1942. Past Barmitzvah pupils one by one stood up and identified themselves. Unhesitatingly Cantor Immerman, born blind, affectionately known as “Der Blinder Chazan”, recalled the dates of their barmitzvahs 40 to 60 years ago and the names of their Maftirs. To end the evening Madame Mabella Ott Paneto, the famous singer, originally Mabel Lewin of Oudtshoorn, who had flown in from Switzerland for the occasion came forward with a song called “Memories” which she had composed herself.

The Shabbat morning Shul service was a trip down Memory Lane. Shacharit was davened by Cantor Immerman, and Maftir was done by his ex-pupil Joe Batzofin, who had first sung it 49 years years ago as a Barmitzvah boy. The formal banquet for over 500 guests on the Saturday evening was a grand gesture of the mutual respect of Afrikaner and Jew. Kosher, down to the hiring and transport of crockery and cutlery from Cape Town, it began with Hamotzi. As mentioned earlier, this function was paid for by the Town Council.

Highlights of the memorable evening included an address by Minister Pik Botha, a response in flawless Afrikaans by Mervyn Smith, a Toast by the Mayor, Councillor A. J. de Jager, and the presentation on behalf of the Municipality of a magnificent Parochet (Aron Kodesh curtain). Ex Mayor, 94 Year old Mr. Bennie Gillis, proposed a toast to the State President. A special Thanksgiving Service on the Sunday morning in Shul was graced by the presence of government and local dignitaries and a sermon by Rabbi Duschinsky, who ended his sermon with the following words: “The characteristic of this unique community may be found in the fact that almost all of its present members are direct descendants of the original Jewish community. Many of the former residents left for other parts of the country, Israel, and the world at large, the remaining families all continued with the unchanged confluence of their own heritage flowing from the rivers of genuine Lithuanian Jewish traditions and western culture. The old cemetery, kept in dignity to this day, contains epitaphs of the old founders in classical Hebrew conveying the love for Zion, for the holy language, for all that is eternal in Jewish spiritual life.” A sudden shower as people emerged from the Shul was taken as a good omen even though it meant a quick switch of plans from a garden party at the Mayor’s residence next door, to the inside of the house. What can one say at the end of an unforgettable nostalgic trip down memory lane in the presence of the descendants of the second oldest Jewish Community in South Africa but to wish the Oudtshoorn Jewish Community everything of the best for the future.

In my own humble opinion the real reason which moved the early Jews to Oudtshoorn was that here was a place where they could keep the Shabbat in freedom in the manner their fathers had taught them. They came, originally, from Eastern Europe where their lives had been a succession of pogroms. Even in their struggle for survival they were never prepared to compromise their Jewish identity and they maintained their culture, traditions and religion throughout their lives. In conclusion I may mention that that spirit even prevails today in a community numbering seventeen Jewish families.

The Centenary of the Oudsthoorn Jewish Community

from the (South African) Zionist Record, November 1984.

from the (South African) Zionist Record, November 1984.

1) Oudtshoorn - "Yerusholayim b'Dorem Afrika"; Bertha Widan; SA-SIG Newsletter, Vol.4:2, 2003

2) Articles in JewishGen at SA-SIG - 1, 2 and 3.

3) The Jerusalem of South Africa; David Zetler; Jerusalem Post, 25/1/2007.

4) Ostrich-farming Jews mark 120 years in rural South Africa; Michael Belling; Jewish Telegraph Agency, December 2004.

5) Jews and Feathers; Ellman Crasnow; Newsletter of Progressive Jewish Community of East Anglia, 2000.

6) Fires and Feathers: Acculturation, Arson and the Jewish Community in Oudtshoorn, South Africa, 1914-1948; Daniel Coetzee; Jewish History 19: 143-197; 2005.

Sources

The Ark of the Griener Shul

A copy of the Ark in the synagogue in Kelme.

The original was destroyed by the Nazis.

A copy of the Ark in the synagogue in Kelme.

The original was destroyed by the Nazis.

The Queen Street Synagogue

Copyright © 2007-12 Jon Seligman. All Rights Reserved.

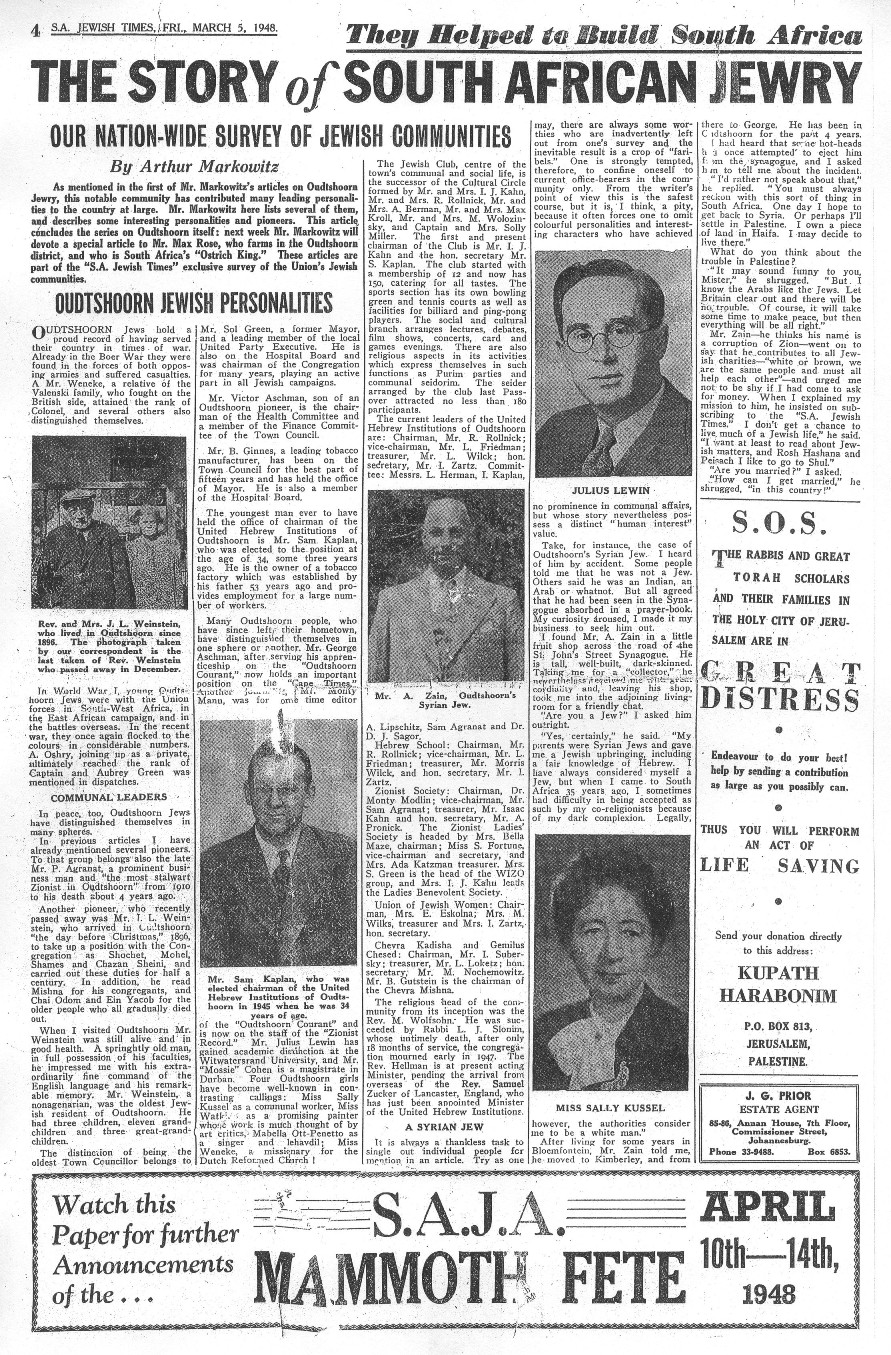

The Story of the Oudtshoorn Jewish Community in the South African Jewish Times 5/3/1948

Benny Gillis is erroneously mentioned as 'Ginnes'

Benny Gillis is erroneously mentioned as 'Ginnes'

CLICK HERE SEE A DOCUMENTARY ON THE JEWISH COMMUNITY OF OUDTSHOORN