Copyright © 2015 Jon Seligman. All Rights Reserved.

HaGra (HaGaon Rabbenu Eliyahu) - The Vilna Gaon

A RESEARCH, EXCAVATION, PRESERVATION AND MEMORIAL PROJECT

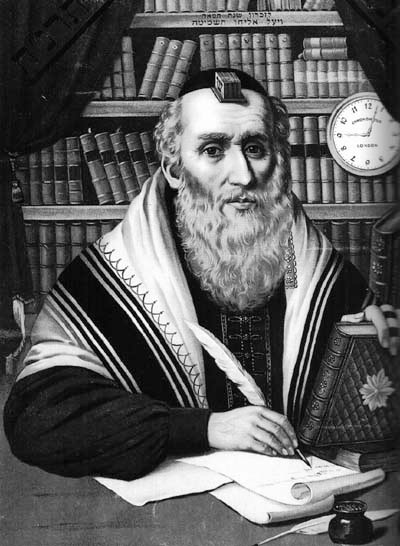

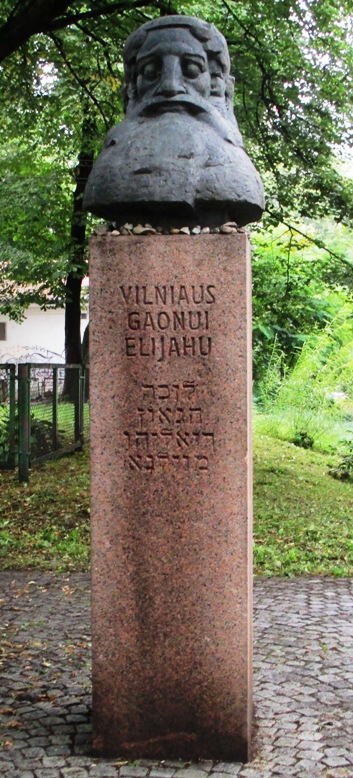

Without question, the outstanding Jewish scholar of Lithuanian Jewry and the founder of the Mitnaged stream of Judaism was Eliyahu ben Solomon Zalman, the Vilna Gaon, also known by his acronym - HaGra. As a world renowned commentator of Torah and Talmud, his powerful intellect and erudition made Vilna and Lithuania a spiritual hub known throughout the Jewish world as a centre for religious learning. Furthermore, it is the association of the Vilna Gaon with the Great Synagogue of Vilna that complements the importance of the edifice. The Synagogue and the shulhoyf became his spiritual and physical home from 1745 till his death in 1797.

Eliyahu Kremer was born in 1720 in Vilna (Vilnius), the son of Solomon Zalman Kremer, a Talmudic scholar in his own right. From his childhood Eliyahu’s studious abilities distinguished him from other boys. At age six, he gave his first sermon in the Great Synagogue of Vilna, where he displayed surprising familiarity of rabbinical literature. In contrast to general practice, Elijah did not study at a yeshiva but conducted independent studies of the Scripture and Talmud, initially under the guidance of Rabbi Moses Margalit in Keidan (Kedainiai).

Later Eliyahu returned to Vilna, where he continued his study, not only of Torah and Talmud, but also of Kabbala, committing the entire Talmud to memory by the age of eleven. Some suggest that this research of the Kabbala strengthened Eliyahu’s affinity for seclusion, which was already observed during his childhood. Indeed, at the age of twenty, Eliyahu abandoned his wife and children to wander around cities and towns of Poland and Germany. In 1748, after five years of drifting, Eliyahu returned to Vilna and remained there until his death. He established his home in a courtyard of Zydu street, directly beside the Great Synagogue, where he established a small study hall, a Bet Midrash, in the adjacent shulhoyf. The Vilna Gaon, known for his modesty and asceticism, always declined the office of rabbi, though it was often offered to him on lucrative terms. He led a secluded life, only lecturing from time to time to a few chosen pupils.

The Vilna Gaon created a new process for researching the Bible (Mikra), the Mishna and the Talmud, applying proper philological methods. He attempted critical examination of the text, often with a single reference to a parallel passage, overthrowing tenuous decisions made by his rabbinic predecessors.

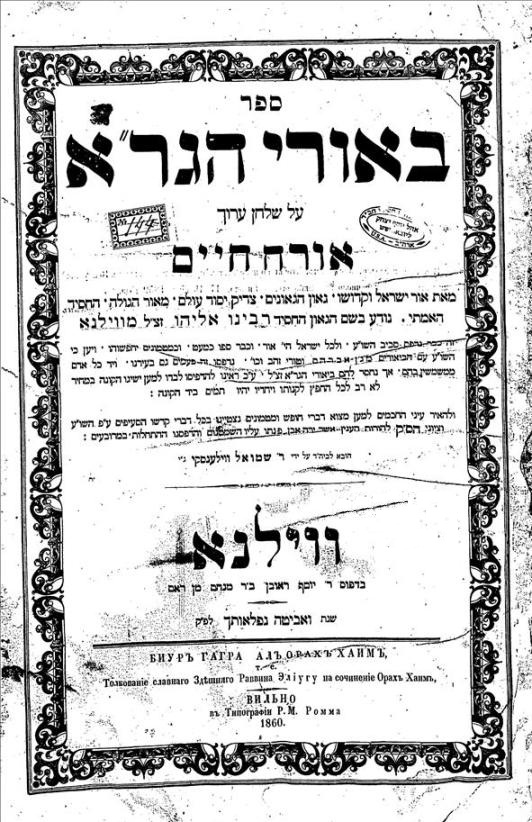

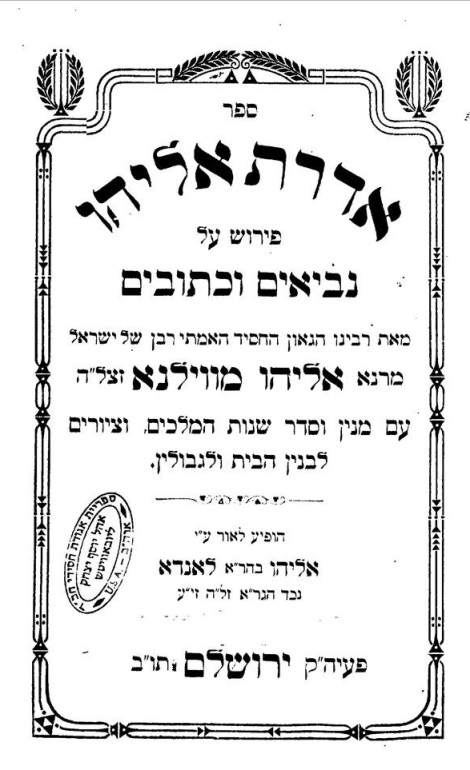

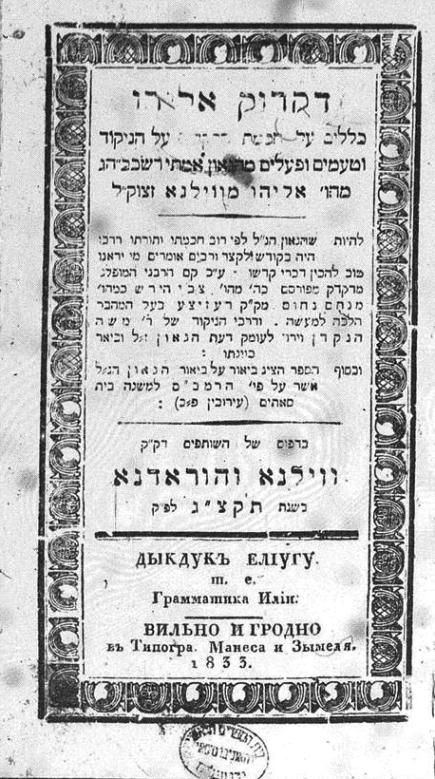

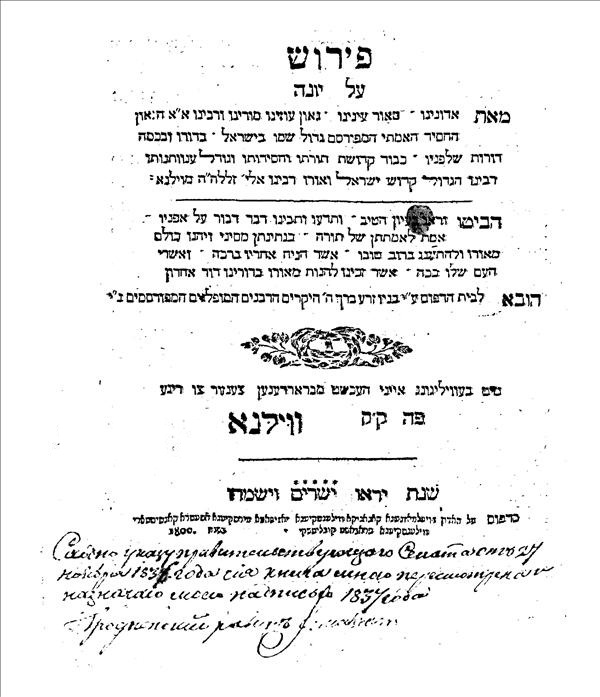

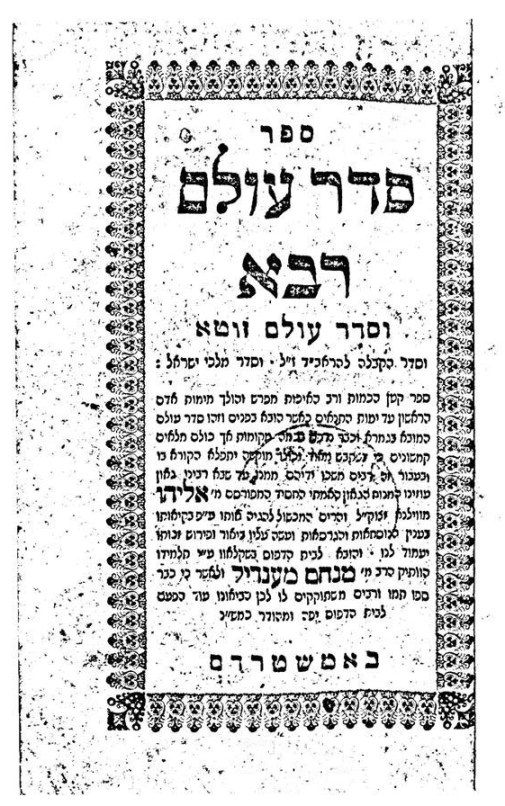

Though none of his manuscripts were published in his lifetime, the intellectual heritage of the Vilna Gaon included glosses and commentaries on Mikra, Mishnah, Talmud, Kabbala and Hebrew grammar. His important books, such as commentary of Shulchan Aruch known as Bi'urei ha-Gra (Elaborations by the Gra); Shnot Eliyahu (The Years of Elijah), a running commentary on the Mishnah; insights on the Torah entitled Adereth Eliyahu (The Splendor of Elijah) published by his son; and Kabbalistic commentaries such as Tikkunei Ha-Zohar and Tikunim Ha-Zohar HaKhadash. Many of these books are still studied in yeshivot (seminaries) today. Indeed, many yeshivot uphold the set of Jewish customs and rites known as the ‘Minhag ha-Gra’, named for the Gaon, considered by many to be the prevailing Ashkenazi tradition in Jerusalem. But it was not only his mastery of Jewish religious texts that was so notable, but also his erudite knowledge of many secular sciences. His writings also consisted of more than seventy treatises on various topics such as general sciences including geometry, astronomy, medicine and so on, as well as translating books on secular science into to Yiddish and Hebrew.

The Vilna Gaon stridently objected to Hasidic Judaism. The opposers, such as the Gaon hinself, known as Mitnagdim, attempted to curb mystical Hasidic influence, even leading a Kherem (excommunicative ban) of the nascent Hasidic movement. The Gaon declared the Hasidim to be heretics with whom no pious Jew might intermarry. However, the excommunications did not stop the tide of Hasidism, while Hasdism itself adopted many of the studious teaching practices of traditional Judaism. The intellectual Jewish tendency represented by the Mitnagdim, that so characterised Lithuanian Jewry, in the tradition of the Vilna Gaon, was distinctive for its synthesis of religious imperative and rational thinking. A key point of the Gaon's opposition was that he maintained that greatness in Torah and observance must come through natural human efforts at Torah study without relying on any external miracles. This tradition became deeply rooted in the instruction of the famous yeshivot in Lithuania, through the rabbis, cantors and Talmudic scholars who followed the teachings of the Gaon.

On his passing, the Vilna Gaon was interred in the Old Cemetery in Shnipishok, just north of the Vilia (neris) river. Over this grave an Ohel (mausoleum, lit. tent) was constructed and the remains of close family members and important rabbinical followers were buried in or around the the Ohel. In the 1950s the Jewish cemetery was destroyed and the remains of the Gaon, together with a small number additional graves were reinterred in a new Ohel in the Sheshkines neighbourhood in northern Vilnius.

Eliyahu Kremer was born in 1720 in Vilna (Vilnius), the son of Solomon Zalman Kremer, a Talmudic scholar in his own right. From his childhood Eliyahu’s studious abilities distinguished him from other boys. At age six, he gave his first sermon in the Great Synagogue of Vilna, where he displayed surprising familiarity of rabbinical literature. In contrast to general practice, Elijah did not study at a yeshiva but conducted independent studies of the Scripture and Talmud, initially under the guidance of Rabbi Moses Margalit in Keidan (Kedainiai).

Later Eliyahu returned to Vilna, where he continued his study, not only of Torah and Talmud, but also of Kabbala, committing the entire Talmud to memory by the age of eleven. Some suggest that this research of the Kabbala strengthened Eliyahu’s affinity for seclusion, which was already observed during his childhood. Indeed, at the age of twenty, Eliyahu abandoned his wife and children to wander around cities and towns of Poland and Germany. In 1748, after five years of drifting, Eliyahu returned to Vilna and remained there until his death. He established his home in a courtyard of Zydu street, directly beside the Great Synagogue, where he established a small study hall, a Bet Midrash, in the adjacent shulhoyf. The Vilna Gaon, known for his modesty and asceticism, always declined the office of rabbi, though it was often offered to him on lucrative terms. He led a secluded life, only lecturing from time to time to a few chosen pupils.

The Vilna Gaon created a new process for researching the Bible (Mikra), the Mishna and the Talmud, applying proper philological methods. He attempted critical examination of the text, often with a single reference to a parallel passage, overthrowing tenuous decisions made by his rabbinic predecessors.

Though none of his manuscripts were published in his lifetime, the intellectual heritage of the Vilna Gaon included glosses and commentaries on Mikra, Mishnah, Talmud, Kabbala and Hebrew grammar. His important books, such as commentary of Shulchan Aruch known as Bi'urei ha-Gra (Elaborations by the Gra); Shnot Eliyahu (The Years of Elijah), a running commentary on the Mishnah; insights on the Torah entitled Adereth Eliyahu (The Splendor of Elijah) published by his son; and Kabbalistic commentaries such as Tikkunei Ha-Zohar and Tikunim Ha-Zohar HaKhadash. Many of these books are still studied in yeshivot (seminaries) today. Indeed, many yeshivot uphold the set of Jewish customs and rites known as the ‘Minhag ha-Gra’, named for the Gaon, considered by many to be the prevailing Ashkenazi tradition in Jerusalem. But it was not only his mastery of Jewish religious texts that was so notable, but also his erudite knowledge of many secular sciences. His writings also consisted of more than seventy treatises on various topics such as general sciences including geometry, astronomy, medicine and so on, as well as translating books on secular science into to Yiddish and Hebrew.

The Vilna Gaon stridently objected to Hasidic Judaism. The opposers, such as the Gaon hinself, known as Mitnagdim, attempted to curb mystical Hasidic influence, even leading a Kherem (excommunicative ban) of the nascent Hasidic movement. The Gaon declared the Hasidim to be heretics with whom no pious Jew might intermarry. However, the excommunications did not stop the tide of Hasidism, while Hasdism itself adopted many of the studious teaching practices of traditional Judaism. The intellectual Jewish tendency represented by the Mitnagdim, that so characterised Lithuanian Jewry, in the tradition of the Vilna Gaon, was distinctive for its synthesis of religious imperative and rational thinking. A key point of the Gaon's opposition was that he maintained that greatness in Torah and observance must come through natural human efforts at Torah study without relying on any external miracles. This tradition became deeply rooted in the instruction of the famous yeshivot in Lithuania, through the rabbis, cantors and Talmudic scholars who followed the teachings of the Gaon.

On his passing, the Vilna Gaon was interred in the Old Cemetery in Shnipishok, just north of the Vilia (neris) river. Over this grave an Ohel (mausoleum, lit. tent) was constructed and the remains of close family members and important rabbinical followers were buried in or around the the Ohel. In the 1950s the Jewish cemetery was destroyed and the remains of the Gaon, together with a small number additional graves were reinterred in a new Ohel in the Sheshkines neighbourhood in northern Vilnius.

The Vilna Gaon

The Original & New Ohelim of the Vilna Gaon

Eliyahu Stern, Assistant Professor of Modern Jewish Intellectual and Cultural History at Yale University, discusses the intellectual method of the Vilna Gaon and his book, 'The Genius - Elijah of Vilna and the Making of Modern Judaism'

Works of HaGra The Vilna Gaon

The Gaon's Kloyz - Beit Midrash of HaGra in the Shulhof

The Beit Midrash (Study House) of HaGra, the Gaon’s Kloyz (kloyz - small prayer and study house), occupies the place of a building where the Vilna Gaon, Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman lived, in the shulhoyf, directly opposite the entrance to the Great Synagogue. In 1768 his wealthy relative Eliyahu Barats Peseles (d. 1771) bought the house, reconstructed it and on its first floor established a permanent minyan for the Gaon and his students. After the death of the Gaon in 1797, it was decided to convert his minyan into a kloyz. In 1799, after conflicts between the Gaon’s children and his students were settled in court and neighbouring apartments bought, the kloyz was established in this house. Russian official documents from the 19th and early 20th century name the kloyz as “the prayer house of the Famous Rabbi Eliash” or “Eliashevskaia prayer house.”

The Gaon’s Kloyz was one of the most prominent prayer and study houses in Vilnius. Among many other outstanding personalities, Rabbi Avraham Danzig (1748-1820), author of Khayei Adam and father-in-law of one of the Gaon’s sons, used to pray in this kloyz. Jewish women used to come to the kloyz and pray at its Torah ark for the healing of their relatives.

Support for the Torah scholars studying in the kloyz came from the endowment of Yittzak Aizik from Hitovich made in 1801. By 1916 the kloyz owned several properties in the Old Jewish quarter, including two shops and an apartment on the ground floor of its own building, and two apartments on the ground floor of the building of the New Kloyz. In the same year 13 prominent Talmudic scholars received a monthly stipend of 20 rubles for learning in the kloyz and the number of regular worshippers reached 50; this number was the same in 1935. Even benches were made in a way convenient for study: the people sat back to back and each one had a shtender (lectern) for the book he was studying.

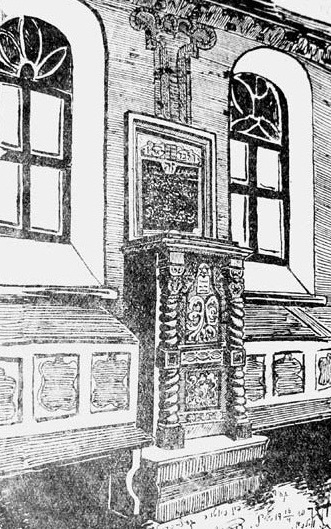

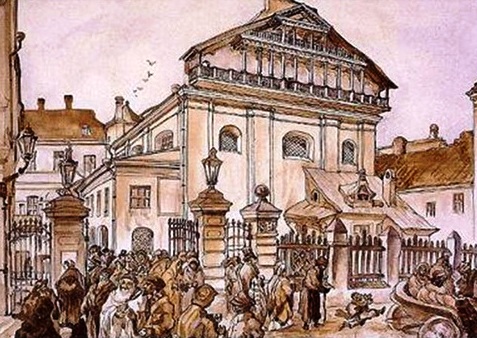

Initially the building of the kloyz was small and narrow; the drawing from 1834 shows it as a small two-story house. In 1855 the kloyz was enlarged by including a neighboring apartment. Finally, it was completely reconstructed on the initiative of Yirakhmiel Broide in 1867-68. The south-eastern street façade had a symmetrical composition: a central blank window, two wide segment-headed windows on its sides and two regular segment-headed windows on the edges. The gable with a central window and flanking oculi crowned the façade. The blank window, which marked the interior position of the Torah ark, bore an inscription in Hebrew: 'Beit Midrash / of the Gaon Rabbi Eliyahu / of blessed memory, / established during his lifetime / in the year 1758 / and built anew / in the year 1868'. A similar inscription was placed at the entrance porch on the northeastern façade, opposite to the Great Synagogue. In the interior, the prayer hall was enlarged and its ceiling heightened. The new Torah Ark was flanked with two pairs of Corinthian columns. The ceiling was decorated with moldings and painted stars. The only known color depiction of the kloyz’s interior is a painting by Marc Chagall made during his visit to Vilna in 1935. He shows that the walls of the kloyz were painted green and the windows had red, blue and yellow colour glazing.

The place where the Gaon used to sit and study was marked by a wooden chest with a marble plaque above it at the middle of the northeastern wall. The decorated chest, which is today in the Spertus Institute in Chicago, was apparently made in 1868 and bears an Hebrew inscription: ‘The place of the Gaon Rabbi Eliyahu / may the memory of the righteous be blessed and last in the future world / born in the year 1720 / on the first day of Passover / and passed away in the year / 1797 / the third day of Sukkot’.

Though the Gaon’s Kloyz was burnt during WWII, its structure remained intact. Post war pictures, which can be viewed here, show the building to be both complete and restorable. However the Lithuanian Soviet authorities decided that the kloyz should be demolished, together with the Great Synagogue and the other buildings of the shulhof in the late 1950s. While the facade of the kloyz is on the edge of the school grounds that occupy the space today,most of the site of the building lies on the road dividing the school from the new apartments to the west.

The Gaon’s Kloyz was one of the most prominent prayer and study houses in Vilnius. Among many other outstanding personalities, Rabbi Avraham Danzig (1748-1820), author of Khayei Adam and father-in-law of one of the Gaon’s sons, used to pray in this kloyz. Jewish women used to come to the kloyz and pray at its Torah ark for the healing of their relatives.

Support for the Torah scholars studying in the kloyz came from the endowment of Yittzak Aizik from Hitovich made in 1801. By 1916 the kloyz owned several properties in the Old Jewish quarter, including two shops and an apartment on the ground floor of its own building, and two apartments on the ground floor of the building of the New Kloyz. In the same year 13 prominent Talmudic scholars received a monthly stipend of 20 rubles for learning in the kloyz and the number of regular worshippers reached 50; this number was the same in 1935. Even benches were made in a way convenient for study: the people sat back to back and each one had a shtender (lectern) for the book he was studying.

Initially the building of the kloyz was small and narrow; the drawing from 1834 shows it as a small two-story house. In 1855 the kloyz was enlarged by including a neighboring apartment. Finally, it was completely reconstructed on the initiative of Yirakhmiel Broide in 1867-68. The south-eastern street façade had a symmetrical composition: a central blank window, two wide segment-headed windows on its sides and two regular segment-headed windows on the edges. The gable with a central window and flanking oculi crowned the façade. The blank window, which marked the interior position of the Torah ark, bore an inscription in Hebrew: 'Beit Midrash / of the Gaon Rabbi Eliyahu / of blessed memory, / established during his lifetime / in the year 1758 / and built anew / in the year 1868'. A similar inscription was placed at the entrance porch on the northeastern façade, opposite to the Great Synagogue. In the interior, the prayer hall was enlarged and its ceiling heightened. The new Torah Ark was flanked with two pairs of Corinthian columns. The ceiling was decorated with moldings and painted stars. The only known color depiction of the kloyz’s interior is a painting by Marc Chagall made during his visit to Vilna in 1935. He shows that the walls of the kloyz were painted green and the windows had red, blue and yellow colour glazing.

The place where the Gaon used to sit and study was marked by a wooden chest with a marble plaque above it at the middle of the northeastern wall. The decorated chest, which is today in the Spertus Institute in Chicago, was apparently made in 1868 and bears an Hebrew inscription: ‘The place of the Gaon Rabbi Eliyahu / may the memory of the righteous be blessed and last in the future world / born in the year 1720 / on the first day of Passover / and passed away in the year / 1797 / the third day of Sukkot’.

Though the Gaon’s Kloyz was burnt during WWII, its structure remained intact. Post war pictures, which can be viewed here, show the building to be both complete and restorable. However the Lithuanian Soviet authorities decided that the kloyz should be demolished, together with the Great Synagogue and the other buildings of the shulhof in the late 1950s. While the facade of the kloyz is on the edge of the school grounds that occupy the space today,most of the site of the building lies on the road dividing the school from the new apartments to the west.

Sources:

Cohen-Mushlin A., Kravtsov S., Levin V., Mickunaite G., Šiauciunaite-Verbickiene J., 2012, Synagogues

in Lithuania , II, Vilnius Academy of Arts Press, Vilnius, Pp. 297-301.

Leiman S.Z. Who is Buried in the Vilna Gaon’s Tomb? A Contribution Toward the Identification of the Authentic Grave of the Vilna Gaon. - The Seforim Blog, http://archive.feedblitz.com/57678/~4239621, accessed 3/10/2015.

Vilna Gaon - Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vilna_Gaon, accessed 3/10/2015.

Vilna Gaon Elijah Ben Solomon Zalman (1720-1797) - The Vilna Gaon Sate Jewish Museum, http://www.jmuseum.lt/index.aspx?Element=ViewArticle&TopicID=201, accessed 3/10/2015

Cohen-Mushlin A., Kravtsov S., Levin V., Mickunaite G., Šiauciunaite-Verbickiene J., 2012, Synagogues

in Lithuania , II, Vilnius Academy of Arts Press, Vilnius, Pp. 297-301.

Leiman S.Z. Who is Buried in the Vilna Gaon’s Tomb? A Contribution Toward the Identification of the Authentic Grave of the Vilna Gaon. - The Seforim Blog, http://archive.feedblitz.com/57678/~4239621, accessed 3/10/2015.

Vilna Gaon - Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vilna_Gaon, accessed 3/10/2015.

Vilna Gaon Elijah Ben Solomon Zalman (1720-1797) - The Vilna Gaon Sate Jewish Museum, http://www.jmuseum.lt/index.aspx?Element=ViewArticle&TopicID=201, accessed 3/10/2015

Exterior & Interior Views of the Gaon's Kloyz

Photographs Prior to the Demolition of the Gaon's Kloyz

The Interior of the Gaon's Kloyz

This site is best viewed in Internet Explorer or Firefox

[The Project] [Community] [Partners] [The Team] [The Synagogue] [Previous Work] [GPR Survey] [Media] [Links]