Copyright © 2015 Jon Seligman. All Rights Reserved.

After the construction of the Great Synagogue in 1633, smaller prayer houses (kloyz - singular, kloyzn - plural) sprang up quickly, initially in the shulhoyf, but later throughout the Jewish neighbourhoods of Vilna. Vilna‘s Jews, known for their religious devotion, were proud of the large number of synagogues and kloyzn in Vilnius and the important rabbis, especially the Vilna Gaon, and Talmudic scholars associated with them.

The first kloyz, unsurprisingly named the Old Kloyz, was located in the shulhoyf. Later, during the 18th century new kloyzn were established by various religious and professional associations, as well as by private individuals. Initially, the kloyzn were established in different courtyards in the vicinity of the shulhoyf, and from the early 19th century they spread throughout the city. In the late 18th and the first half of the 19th century, the prominent members of the Jewish elite established private kloyzn in their houses, to emphasise their social status, wealth through devotion to Torah study. By the early 20th century, many formerly private kloyzn in the city center passed on to various trade and craft associations, the majority of Vilna‘s kloyzn, especially those in the old town, were situated in regular dwelling houses. Jewish institutions also had kloyzn on their premises: the hospital, the almshouse, the soup kitchen, the Talmud Torah, the Rabbinic Seminary and others. With the settlement of Jews in the suburbs of Vilna, the synagogues and kloyzn were built there too.

Some kloyzn became home to Yeshivot, or groups of Talmudic scholars, supported by the worshippers. Indeed, many kloyzn hired a Talmudic scholar (maggid shi’ur) in order to provide lessons in sacred texts for the worshippers. Some kloyzn served also as headquarters for charity associations (gmilut hasadim) organized by the worshippers, which provided interest free loans for their members and for the needy.

Six synagogues, 33 prayer houses and 127 minyanim existed in Vilna in 1833-34, eight of them situated in the shulhoyf, the courtyard surrounded the Great Synagogue itself. By 1887 there were 93 kloyzn, many of them associated with specific craftsmen. Officially, in 1925 and 1936, the years prior to the Holocaust, 105 kloyzn were officially registered. The actual numbers of prayer houses may well have been different, for example, the librarian of the Strashun Library, Khaykl Lunski, listed 80 kloyzn in his book written in 1917, while 110 synagogues, batei midrash and kloyzn were described in the report prepared for the Judenrat in late 1941 and early 1942, on demand of the Vilnius Headquarters of the Einsatzstab Rosenberg - a Nazi institution invested with collecting Jewish cultural treasures. Modern research has shown the even this number was too low, Vladimir Levin listing 154 institutions of prayer in Vilna in 1939 in his seminal article on the synagogues of Vilna. It is this article, listed below, that forms the basis for the following description of the Great Synagogue and shulhoyf.

Of these synagogues, it was the Great Synagogue, surrounded by the shulhoyf which contained twelve prayer halls (ten kloyzn and two stiblach) that were the most prestigious, the oldest and the most culturally important, especially given the association of the complex with the Vilna Gaon. It is these which are described here, in brief summary above and below in detail.

The first kloyz, unsurprisingly named the Old Kloyz, was located in the shulhoyf. Later, during the 18th century new kloyzn were established by various religious and professional associations, as well as by private individuals. Initially, the kloyzn were established in different courtyards in the vicinity of the shulhoyf, and from the early 19th century they spread throughout the city. In the late 18th and the first half of the 19th century, the prominent members of the Jewish elite established private kloyzn in their houses, to emphasise their social status, wealth through devotion to Torah study. By the early 20th century, many formerly private kloyzn in the city center passed on to various trade and craft associations, the majority of Vilna‘s kloyzn, especially those in the old town, were situated in regular dwelling houses. Jewish institutions also had kloyzn on their premises: the hospital, the almshouse, the soup kitchen, the Talmud Torah, the Rabbinic Seminary and others. With the settlement of Jews in the suburbs of Vilna, the synagogues and kloyzn were built there too.

Some kloyzn became home to Yeshivot, or groups of Talmudic scholars, supported by the worshippers. Indeed, many kloyzn hired a Talmudic scholar (maggid shi’ur) in order to provide lessons in sacred texts for the worshippers. Some kloyzn served also as headquarters for charity associations (gmilut hasadim) organized by the worshippers, which provided interest free loans for their members and for the needy.

Six synagogues, 33 prayer houses and 127 minyanim existed in Vilna in 1833-34, eight of them situated in the shulhoyf, the courtyard surrounded the Great Synagogue itself. By 1887 there were 93 kloyzn, many of them associated with specific craftsmen. Officially, in 1925 and 1936, the years prior to the Holocaust, 105 kloyzn were officially registered. The actual numbers of prayer houses may well have been different, for example, the librarian of the Strashun Library, Khaykl Lunski, listed 80 kloyzn in his book written in 1917, while 110 synagogues, batei midrash and kloyzn were described in the report prepared for the Judenrat in late 1941 and early 1942, on demand of the Vilnius Headquarters of the Einsatzstab Rosenberg - a Nazi institution invested with collecting Jewish cultural treasures. Modern research has shown the even this number was too low, Vladimir Levin listing 154 institutions of prayer in Vilna in 1939 in his seminal article on the synagogues of Vilna. It is this article, listed below, that forms the basis for the following description of the Great Synagogue and shulhoyf.

Of these synagogues, it was the Great Synagogue, surrounded by the shulhoyf which contained twelve prayer halls (ten kloyzn and two stiblach) that were the most prestigious, the oldest and the most culturally important, especially given the association of the complex with the Vilna Gaon. It is these which are described here, in brief summary above and below in detail.

The Great Synagogue & Shulhof of Vilna (Vilnius)

A RESEARCH, EXCAVATION, PRESERVATION AND MEMORIAL PROJECT

The Synagogues, Batei Midrash and Kloyzn of Vilna (Vilnius)

A Quick Summary

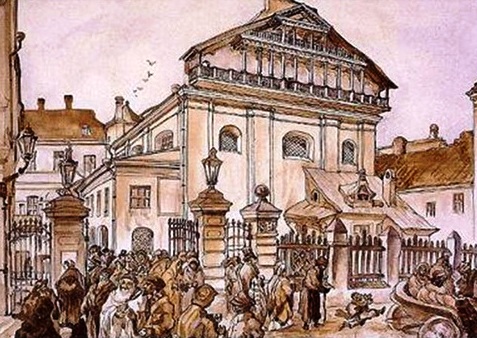

The Great Synagogue of Vilna was built between 1633 and 1635, in Renaissance-Baroque style, after permission was given to build a stone structure to replace the Old Synagogue purportedly built in 1573. Over the course of time the Great Synagogue was surrounded with other buildings within the labyrinth-like Shulhoyf, a complex of twelve synagogues and other communal institutions, that included the premises of the community Board (kahal-shtub), the Old Kloyz, the synagogue of the Chevra Kadisha (Burial Society), the Shiv’ah Kru’im Kloyz, the New Kloyz of Yesod, the Kloyz of Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman - the Vilna Gaon, the Gmilut Hesed Kloyz, the Painter’s Kloyz, the Artizan’s Kloyz Chevra Po’alim, the Shtibl of the Koidanover Hasidim, the Shtibl of the Lubavich Hasidim (later Tiferet Bahurim Kloyz), as well as the community’s bathhouse with a miqveh, a public lavatory, a communal “well,” communal kosher meat stalls, and the famous Strashun Library. The whole complex became a great centre of Torah study and the heart of the Lithuanian Jewish movement of Mitnagdim.

The Great City Synagogue was a tall one-story building with a slanted roof. Ecclesiastical restrictions specified that a synagogue could not be built higher than a church. To obey the law, and yet create necessary interior height, the level of the synagogue’s floor was set well below that of the street. Outside, the synagogue looked three stories tall, but inside it soared to over five stories. In the early nineteenth century a gable with a two-tiered wooden gallery was added on the western side. The entrance, with a vestibule, was located on the northern side of the building. The main prayer hall was square and could hold about 450 people. It had a three-tiered bimah in the center, set between four pillars in Tuscan style. The lower tier of the bimah was composed of twelve columns, while the upper supporting an ornate dome. The splendid two-tiered Aron Kodesh on the eastern wall was decorated with stucco carvings, representing vegetative, animal and Jewish symbols. The ark was approached by a twofold flight of steps, with iron balustrades. Hanging from the walls and ceilings there were numerous bronze and silver chandeliers and the synagogue also contained a valuable collection of ritual objects. On the northeastern and northwestern sides of the prayer hall there were two-storey structures, serving as the ezrat nashim (women’s sections), connected to the hall by small windows.

After centuries of existence, with the destruction of the entire Jewish community of Vilnius, this most important shrine of the Jews of Lithuania was ransacked and burnt by the Germans during World War II. Despite attempts to preserve the remnants of the Great Synagogue in the late 1940s, the Soviet authorities demolished it together with other structures of the Shulhoyf. In their place a brick built elementary school was constructed in a typically Soviet unpretentious manner. The Vyte Nemunelis school, which covers half of the remains of the synagogue, operates till today.

The Great City Synagogue was a tall one-story building with a slanted roof. Ecclesiastical restrictions specified that a synagogue could not be built higher than a church. To obey the law, and yet create necessary interior height, the level of the synagogue’s floor was set well below that of the street. Outside, the synagogue looked three stories tall, but inside it soared to over five stories. In the early nineteenth century a gable with a two-tiered wooden gallery was added on the western side. The entrance, with a vestibule, was located on the northern side of the building. The main prayer hall was square and could hold about 450 people. It had a three-tiered bimah in the center, set between four pillars in Tuscan style. The lower tier of the bimah was composed of twelve columns, while the upper supporting an ornate dome. The splendid two-tiered Aron Kodesh on the eastern wall was decorated with stucco carvings, representing vegetative, animal and Jewish symbols. The ark was approached by a twofold flight of steps, with iron balustrades. Hanging from the walls and ceilings there were numerous bronze and silver chandeliers and the synagogue also contained a valuable collection of ritual objects. On the northeastern and northwestern sides of the prayer hall there were two-storey structures, serving as the ezrat nashim (women’s sections), connected to the hall by small windows.

After centuries of existence, with the destruction of the entire Jewish community of Vilnius, this most important shrine of the Jews of Lithuania was ransacked and burnt by the Germans during World War II. Despite attempts to preserve the remnants of the Great Synagogue in the late 1940s, the Soviet authorities demolished it together with other structures of the Shulhoyf. In their place a brick built elementary school was constructed in a typically Soviet unpretentious manner. The Vyte Nemunelis school, which covers half of the remains of the synagogue, operates till today.

Vilnius, Vilna, Vilne, Wilno - 'Yerushalayim de-Lita' (Jerusalem of Lithuania)

A Short Film about Jewish Vilna in 1939.

Excellent views of the Great Synagogue and Shulhoyf can be seen between 2:47 - 4:52.

Excellent views of the Great Synagogue and Shulhoyf can be seen between 2:47 - 4:52.

It is impossible to describe the Great Synagogue of Vilna without a short introduction about the Synagogue’s context, as the premier institution of the Jewish community of Vilna, today Vilnius, the capital of the Republic of Lithuania. The Jewish quarter, with the Great Synagogue at its heart, is located within the old town of Vilnius, that has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1994. Known by Jewish tradition as Yerushaliym D’Lita - Jerusalem of Lithuania because of the importance of the community, Vilnius was first mentioned as the capital in 1323, in the letters of the Grand Duke Gediminas in which he invited foreign craftsmen and merchants to settle in the city. In 1387, on the occasion of conversion of the Grand Duchy to Catholicism, the King of Poland and the Grand Duke of Lithuania Wladyslaw II Jagiello - Jogaila established the Bishopric of Vilnius and granted the Magdeburg law to the city.

After the third partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795 Vilnius became the center of a province and the most important city in the northwestern region of the Russian Empire. In 1915 the city was occupied by the Germans and in 1920 was conquered by the Polish army. Vilnius was transferred to Lithuania in 1940 and since then serves as its capital.

The time when Jews first began settling in Vilnius is unknown. There are legends about Gediminas’ invitation of Jews in the 14th century, about the establishment of the Old Kloyz in 1440 and the founding of the old Jewish cemetery in 1487. Most probably, Jews started settling in Vilnius in the early 16th century and were soon banned from the city by the privilege granted to the Christian burghers by Sigismund I the Old in 1527. According to Jewish tradition, the Great Synagogue of Vilnius was established in 1573, on a plot exempted from municipal jurisdiction. In 1592 this synagogue was plundered by a Christian mob. Apparently, this event caused Jews to make efforts for obtaining in 1593 a privilege from Sigismund III Vasa, which allowed them to settle in the city, build a synagogue, establish a cemetery and engage in trade.

In 1606 the synagogue was again attacked by a Christian mob. On February 25, 1633, Wladyslaw IV Vasa, responding to the Jews’ request, granted a privilege which reads: “for the purpose of security and better protection from fire, permission is given to build a synagogue in our city of Vilnius, on Jewish Street, which is densely lined up with buildings ..., on the same plot where it stands now.” In this way the construction of the masonry Great Synagogue was sanctioned. The shulhoyf grew around the Great Synagogue, and by the early 20th century it included twelve houses of prayer.

In 1633, by a separate privilege, Vilnius' Jews were assigned a quarter or ghetto limited by today’s streets: Žydu (Jewish), Vokieciu (German), and Šv. Mikalojaus (St. Nicholas), in the 19th century known among Jews as Gitke-Toybe’s Lane and by one side of Marko Antokolskio (former Miasnaia or Jatkowa) Street adjacent to Žydu Street. Despite the burghers’ attempts, Jews never confined themselves solely to their officially assigned part in the city and lived on other streets as well. The limitation of abode to the Jewish quarter was abolished in 1783, and Jews were allowed to live in the entire city with the exception of two main roads. Reconfirmed by the imperial Russian authorities, this prohibition was in force until 1861.

By the first half of the 17th century the Vilna Jewish community was one of the largest in Eastern Europe, but the occupation of the city by the Muscovite army in 1655-61 harmed it severely.

During the 18th century the community was overburdened with debts to private lenders and ecclesiastical officials. During this time Rabbi Eliyahu son of Shlomo Zalman (1720-97), the Gaon of Vilna, renown for his method of Torah study, became the most illustrious Torah scholar in the East European Jewish world. The Gaon rarely participated in communal life; most of his time was spent in seclusion, studying Torah with a small group of students.

At that period the most influential figure in the Vilnius community was Yehudah son of Eliezer (d. 1762), known under the acronym Yesod (Yehudah Safra ve-Dayana - Judah writer and Judge). The rich and well-connected Yesod settled conflicts between the community and the municipality and influenced communal affairs, including the appointment of his son-in-law, Shmuel, to the position of the chief rabbi of Vilnius in 1750. Following Yesod’s death, the Kahal wanted to remove Rabbi Shmuel. The conflict continued for 30 years, involving the Kahal authorities and courts of law. As a result, in 1785 the position of the chief rabbi of the city was abolished, and the rabbinical affairs were dealt by several local rabbinic figures. A large stone was placed on the chief rabbi’s seat near the Aron Kodesh (Torah Ark) in the Great Synagogue, so that no one would sit there.

Under the Tsarist rule in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Vilna became one of the most important political, cultural, educational, societal and religious centers of Russia’s Jewry. The city continued to be the center of Torah study, and its rabbis, Talmudic scholars, yeshivot and batei midrash were held in high esteem. Moreover, until the 1870s the Vilnius Jewish community played a major role in representing Jews before the Imperial authorities.

Jewish secularism also took hold in Vilna, the city becoming was one of the major centers of the Haskalah - Jewish Enlightenment in Eastern Europe, exhibited through the establishment of private Jewish schools made the city an important center of modern Jewish education in the Russian Empire. The Rabbinical Seminary, established in 1847 was reorganized as the Jewish Teachers Seminary in 1873. The famous Romm printing house was the largest and most important Jewish publishing enterprise at the time and the Strashun Library - one of the richest Jewish book collections.

Vilna was home to many Jewish writers and poets, as well as to the Hebrew newspaper Ha-Karmel published from 1860-80 and 46 other Yiddish and Hebrew periodicals. The Zionist movement found active supporters and between 1906-15 the Central Committee of the Zionist Organization in Russia had its headquarters in the city. Vilna was also the cradle of the Jewish socialist movement, the Jewish Labor Bund was established there in 1897, During the first Russian Revolution of 1905-7, the centers of all Jewish socialist parties in Russia were situated in Vilna and the first political organization of the Orthodox Jewry in the Russian Empire, Knesset Israel, was founded there in 1907-8. At this time Jewish population peaked, reaching 47% of the city’s residents.

During the 18th and the 19th centuries dozens of synagogues were established in Vilnius, but only two of them were constantly referred to as synagogues: the Great Synagogue or di Shtot-Shul (the city synagogue) and the magnificent Taharat Ha-Kodesh Synagogue of the maskilim. All other houses of prayer in the city were usually named kloyzn, established by private persons, religious fraternities, professional or guild associations of merchants and craftsmen, or by Jews living in a neighborhood. Initially they were situated mostly in the old Jewish quarter, but later spread throughout the city.

Under Polish rule in the 1920s and 1930s, Vilna, now Wilno, remained the undisputable capital of the Lithuanian Jewry. While the economic hardship and tensions between Poles and Jews caused the deterioration of the economic situation of the Jewish community, the cultural importance of the city far exceeded its size. Schools belonging to different Jewish ideological trends, Jewish press, theatre and arts flourished. In 1924 the Council of Yeshivot was established as an umbrella organization to the ‘Lithuanian’ yeshivas, and in 1925 the YIVO Institute for studying the Yiddish language and Jewish history, culture and social science was founded.

Vilna was captured by the Nazis on June 24th 1941. Shortly afterwards the murder of tens-of- thousands of Jews began in the nearby Ponar (Paneriai) forest. On September 6, 1941, the Jews were driven into two ghettos situated in the territory of the historical Jewish quarter and the surrounding streets. The small ghetto, in the old Jewish quarter, including the shulhoyf - was liquidated on October 21st 1941 and all its inmates were shot in Ponar. The large ghetto was liquidated on September 23rd 1943. About 70,000 Jews from Vilna and the surrounding region were murdered in Ponar during WWII.

During the Soviet period, in the 1950s, a part of the old Jewish quarter of Vilnius, including the shulhoyf, was pulled down. The Šnipiškes-Old Jewish cemetery on the right bank of the Neris River was destroyed in 1949-50; tombstones from the New Cemetery in Užupis, established in 1830, were taken for building purposes in 1965. Only the third Jewish cemetery in Šeškine, started in 1941 remained.

In the early 1990s, with the re-establishment of Lithuanian independence, memorial monuments were erected on the sites of the former cemeteries, and the buildings connected to the Jewish history of the city were marked with plaques. Only eight synagogue buildings survived in Vilnius, of which only Taharat Ha-Kodesh (the Choral) Synagogue retains its original function. Though now much reduced to around 3,000, the Jewish community of Vilnius has reorganised and today maintains a community organisation for social, cultural and religious support.

After the third partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795 Vilnius became the center of a province and the most important city in the northwestern region of the Russian Empire. In 1915 the city was occupied by the Germans and in 1920 was conquered by the Polish army. Vilnius was transferred to Lithuania in 1940 and since then serves as its capital.

The time when Jews first began settling in Vilnius is unknown. There are legends about Gediminas’ invitation of Jews in the 14th century, about the establishment of the Old Kloyz in 1440 and the founding of the old Jewish cemetery in 1487. Most probably, Jews started settling in Vilnius in the early 16th century and were soon banned from the city by the privilege granted to the Christian burghers by Sigismund I the Old in 1527. According to Jewish tradition, the Great Synagogue of Vilnius was established in 1573, on a plot exempted from municipal jurisdiction. In 1592 this synagogue was plundered by a Christian mob. Apparently, this event caused Jews to make efforts for obtaining in 1593 a privilege from Sigismund III Vasa, which allowed them to settle in the city, build a synagogue, establish a cemetery and engage in trade.

In 1606 the synagogue was again attacked by a Christian mob. On February 25, 1633, Wladyslaw IV Vasa, responding to the Jews’ request, granted a privilege which reads: “for the purpose of security and better protection from fire, permission is given to build a synagogue in our city of Vilnius, on Jewish Street, which is densely lined up with buildings ..., on the same plot where it stands now.” In this way the construction of the masonry Great Synagogue was sanctioned. The shulhoyf grew around the Great Synagogue, and by the early 20th century it included twelve houses of prayer.

In 1633, by a separate privilege, Vilnius' Jews were assigned a quarter or ghetto limited by today’s streets: Žydu (Jewish), Vokieciu (German), and Šv. Mikalojaus (St. Nicholas), in the 19th century known among Jews as Gitke-Toybe’s Lane and by one side of Marko Antokolskio (former Miasnaia or Jatkowa) Street adjacent to Žydu Street. Despite the burghers’ attempts, Jews never confined themselves solely to their officially assigned part in the city and lived on other streets as well. The limitation of abode to the Jewish quarter was abolished in 1783, and Jews were allowed to live in the entire city with the exception of two main roads. Reconfirmed by the imperial Russian authorities, this prohibition was in force until 1861.

By the first half of the 17th century the Vilna Jewish community was one of the largest in Eastern Europe, but the occupation of the city by the Muscovite army in 1655-61 harmed it severely.

During the 18th century the community was overburdened with debts to private lenders and ecclesiastical officials. During this time Rabbi Eliyahu son of Shlomo Zalman (1720-97), the Gaon of Vilna, renown for his method of Torah study, became the most illustrious Torah scholar in the East European Jewish world. The Gaon rarely participated in communal life; most of his time was spent in seclusion, studying Torah with a small group of students.

At that period the most influential figure in the Vilnius community was Yehudah son of Eliezer (d. 1762), known under the acronym Yesod (Yehudah Safra ve-Dayana - Judah writer and Judge). The rich and well-connected Yesod settled conflicts between the community and the municipality and influenced communal affairs, including the appointment of his son-in-law, Shmuel, to the position of the chief rabbi of Vilnius in 1750. Following Yesod’s death, the Kahal wanted to remove Rabbi Shmuel. The conflict continued for 30 years, involving the Kahal authorities and courts of law. As a result, in 1785 the position of the chief rabbi of the city was abolished, and the rabbinical affairs were dealt by several local rabbinic figures. A large stone was placed on the chief rabbi’s seat near the Aron Kodesh (Torah Ark) in the Great Synagogue, so that no one would sit there.

Under the Tsarist rule in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Vilna became one of the most important political, cultural, educational, societal and religious centers of Russia’s Jewry. The city continued to be the center of Torah study, and its rabbis, Talmudic scholars, yeshivot and batei midrash were held in high esteem. Moreover, until the 1870s the Vilnius Jewish community played a major role in representing Jews before the Imperial authorities.

Jewish secularism also took hold in Vilna, the city becoming was one of the major centers of the Haskalah - Jewish Enlightenment in Eastern Europe, exhibited through the establishment of private Jewish schools made the city an important center of modern Jewish education in the Russian Empire. The Rabbinical Seminary, established in 1847 was reorganized as the Jewish Teachers Seminary in 1873. The famous Romm printing house was the largest and most important Jewish publishing enterprise at the time and the Strashun Library - one of the richest Jewish book collections.

Vilna was home to many Jewish writers and poets, as well as to the Hebrew newspaper Ha-Karmel published from 1860-80 and 46 other Yiddish and Hebrew periodicals. The Zionist movement found active supporters and between 1906-15 the Central Committee of the Zionist Organization in Russia had its headquarters in the city. Vilna was also the cradle of the Jewish socialist movement, the Jewish Labor Bund was established there in 1897, During the first Russian Revolution of 1905-7, the centers of all Jewish socialist parties in Russia were situated in Vilna and the first political organization of the Orthodox Jewry in the Russian Empire, Knesset Israel, was founded there in 1907-8. At this time Jewish population peaked, reaching 47% of the city’s residents.

During the 18th and the 19th centuries dozens of synagogues were established in Vilnius, but only two of them were constantly referred to as synagogues: the Great Synagogue or di Shtot-Shul (the city synagogue) and the magnificent Taharat Ha-Kodesh Synagogue of the maskilim. All other houses of prayer in the city were usually named kloyzn, established by private persons, religious fraternities, professional or guild associations of merchants and craftsmen, or by Jews living in a neighborhood. Initially they were situated mostly in the old Jewish quarter, but later spread throughout the city.

Under Polish rule in the 1920s and 1930s, Vilna, now Wilno, remained the undisputable capital of the Lithuanian Jewry. While the economic hardship and tensions between Poles and Jews caused the deterioration of the economic situation of the Jewish community, the cultural importance of the city far exceeded its size. Schools belonging to different Jewish ideological trends, Jewish press, theatre and arts flourished. In 1924 the Council of Yeshivot was established as an umbrella organization to the ‘Lithuanian’ yeshivas, and in 1925 the YIVO Institute for studying the Yiddish language and Jewish history, culture and social science was founded.

Vilna was captured by the Nazis on June 24th 1941. Shortly afterwards the murder of tens-of- thousands of Jews began in the nearby Ponar (Paneriai) forest. On September 6, 1941, the Jews were driven into two ghettos situated in the territory of the historical Jewish quarter and the surrounding streets. The small ghetto, in the old Jewish quarter, including the shulhoyf - was liquidated on October 21st 1941 and all its inmates were shot in Ponar. The large ghetto was liquidated on September 23rd 1943. About 70,000 Jews from Vilna and the surrounding region were murdered in Ponar during WWII.

During the Soviet period, in the 1950s, a part of the old Jewish quarter of Vilnius, including the shulhoyf, was pulled down. The Šnipiškes-Old Jewish cemetery on the right bank of the Neris River was destroyed in 1949-50; tombstones from the New Cemetery in Užupis, established in 1830, were taken for building purposes in 1965. Only the third Jewish cemetery in Šeškine, started in 1941 remained.

In the early 1990s, with the re-establishment of Lithuanian independence, memorial monuments were erected on the sites of the former cemeteries, and the buildings connected to the Jewish history of the city were marked with plaques. Only eight synagogue buildings survived in Vilnius, of which only Taharat Ha-Kodesh (the Choral) Synagogue retains its original function. Though now much reduced to around 3,000, the Jewish community of Vilnius has reorganised and today maintains a community organisation for social, cultural and religious support.

The Shulhoyf

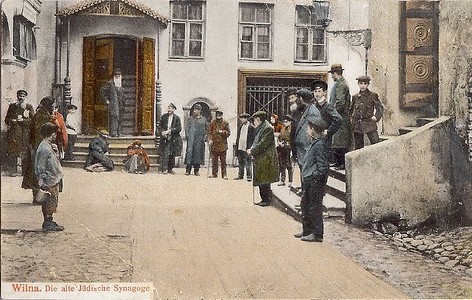

The Vilna shulhoyf developed around the Great Synagogue in the 18th century and occupied an area between today’s Žydu (Jewish) and Vokieciu (German) Streets. If fact the shulhoyf consisted of two courtyards, the first situated between the southwestern façade of the Great Synagogue and the Gaon’s Kloyz, and entered through a gate from Žydu Street and the second, called durchhoyf, included the courtyards of the houses behind the Old Kloyz. The two were connected through the arched passages under the Old Kloyz and through an open passage around the New Kloyz.

The shulhoyf was the true center of Jewish life in Vilnius, a sort of Jewish town square. Besides the twelve kloyzn, the shulhoyf comprised the communal bathhouse, public lavatories and the community’s ‘well’, actually a cistern connected from 1759 with a pipeline to the Vingriu springs that belonged to the Dominican friars. The bathhouse was constructed in 1823-28 and the sewage was channeled to that of the Jesuit monastery.

After the elimination of the ‘Small Ghetto’ on October 21 1941, in which the shulhoyf was located, the shulhoyf was left abandoned, though part of the more valuable religious objects and books were rescued and brought to the Jewish library in the ‘Large Ghetto’. Judging from the photographs made during the war, the shulhoyf was ransacked but not heavily damaged. Additional damage occurred during the liberation of the city in 1944. In 1945 The Great Synagogue and other structures were still standing, although roofless. In 1946 the short lived Jewish Museum of Vilnius tried to list the synagogue as a historic monument and thus to preserve it, but without success. In 1947 the Lithuanian-Soviet authorities blasted the buildings in the shulhoyf and in 1957 completely razed the ruins. Vokieciu Street was widened to occupy the western part of the former shulhoyf and apartment houses were built along the street in the 1950s and 60s.

Luckily the shulhoyf was well documented and frequently depicted by artists and in literary works, both before and after the Holocaust. Furthermore hundreds of photographs of it were made before the Holocaust and prior to its complete demolition.

The shulhoyf was the true center of Jewish life in Vilnius, a sort of Jewish town square. Besides the twelve kloyzn, the shulhoyf comprised the communal bathhouse, public lavatories and the community’s ‘well’, actually a cistern connected from 1759 with a pipeline to the Vingriu springs that belonged to the Dominican friars. The bathhouse was constructed in 1823-28 and the sewage was channeled to that of the Jesuit monastery.

After the elimination of the ‘Small Ghetto’ on October 21 1941, in which the shulhoyf was located, the shulhoyf was left abandoned, though part of the more valuable religious objects and books were rescued and brought to the Jewish library in the ‘Large Ghetto’. Judging from the photographs made during the war, the shulhoyf was ransacked but not heavily damaged. Additional damage occurred during the liberation of the city in 1944. In 1945 The Great Synagogue and other structures were still standing, although roofless. In 1946 the short lived Jewish Museum of Vilnius tried to list the synagogue as a historic monument and thus to preserve it, but without success. In 1947 the Lithuanian-Soviet authorities blasted the buildings in the shulhoyf and in 1957 completely razed the ruins. Vokieciu Street was widened to occupy the western part of the former shulhoyf and apartment houses were built along the street in the 1950s and 60s.

Luckily the shulhoyf was well documented and frequently depicted by artists and in literary works, both before and after the Holocaust. Furthermore hundreds of photographs of it were made before the Holocaust and prior to its complete demolition.

The Great Synagogue of Vilna - Di Shtot-Shul (Yiddish - the City Synagogue)

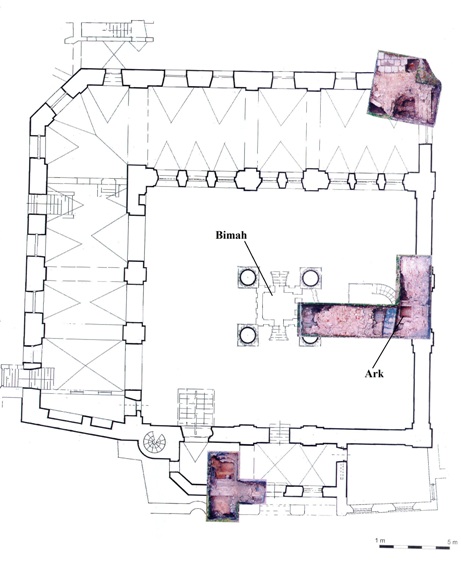

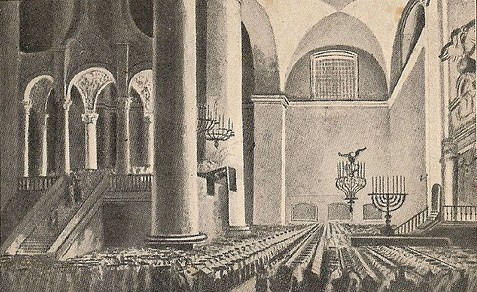

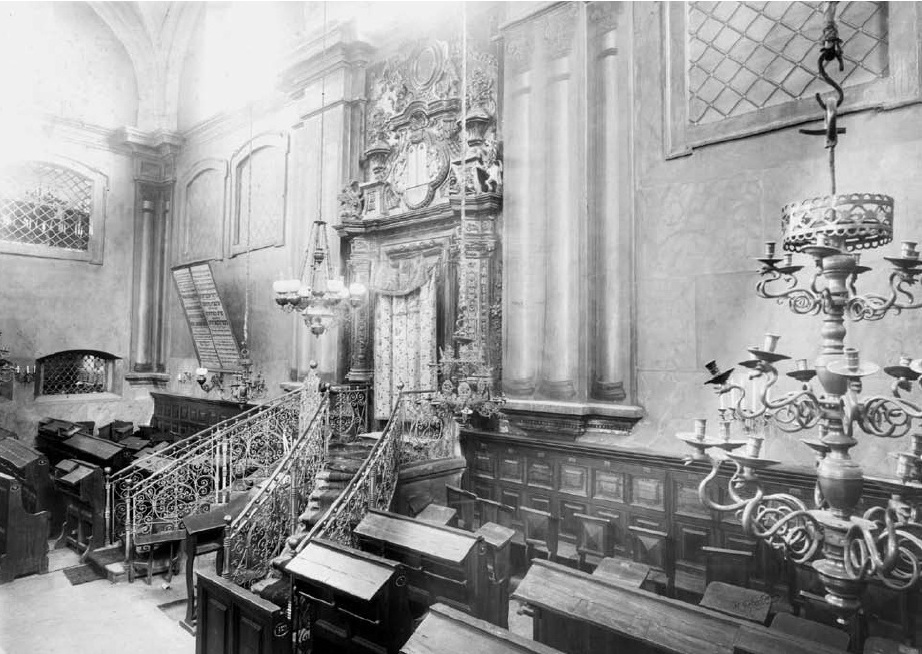

The synagogue was apparently erected after the Vilna Jews received the privilege in 1633 in Renaissance-Baroque style, after permission was given to build a stone structure to replace the Old Synagogue purportedly built in 1573. The Great Synagogue was a large, almost square building, the floor of which was located nearly two metres, or ten steps, below street level to give the interior a lofty appearance, while complying to height restrictions of the building imposed on the community by the authorities. Pilasters divided all four façades into three bays each, corresponding to the interior arrangement of the building. Each bay contained a segment-headed window, placed high above the ground. The central bay of the southeastern façade, marking the interior placement of the Aron Kodesh (the Torah Ark), was narrower than the side bays. Annexes were attached on three sides of the synagogue, so that only the southeastern façade remained exposed, though it was partly concealed by shops and later by the Strashun Library. Thus, only the upper register of the façades with twelve windows of the prayer hall was seen from outside. Even the magnificent southeastern gable, decorated apparently in the early 19th century as two-tiered galleries with Doric and Corinthian columns, was hardly visible from the street. The entire exterior became revealed only during the destruction of the synagogue and the adjacent buildings after WW II.

The prayer hall of the Great Synagogue featured high Tuscan columns standing close together and reaching the spring of the vault, while the perimeter of the prayer hall was spanned by barrel vaults with twelve lunettes above the segment-headed windows. The lower tiers of the walls comprised segment-headed openings connecting the hall with several women’s sections situated in the annexes on the northeastern and northwestern sides of the prayer hall which were rebuilt in the late 18th century. Tuscan pilasters corresponding to the exterior ones divided the walls into bays; at some point in time, Corinthian columns were painted on those pilasters.

Already in March 1635 a Christian mob plundered the synagogue and consequent court files contain detailed descriptions of its furniture and chandeliers. An iron door leading from the polish (vestibule) to the prayer hall was donated by the tailors’ guild in 1640 and the door leading from the street to the polish - by the Magidei Tehilim (Psalms Sayers) Society in 1641. Fires of 1737, 1747 and again in 1748 damaged the Great Synagogue. The mannerist Aron Kodesh at the center of the southeastern wall was renovated by the Bedek Bait (Synagogue maintenance) Association after the fire of 1737 or 1748; a shield with the Tablets of the Law above the ark was donated by Yesod - Yehudah son of Eliezer. This shield, the doors of the Torah ark and the metal shell of the amud were rescued after the Holocaust and are today preserved in the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum. A large Menorah and a splendid chandelier were situated at the back of the prayer hall. At the outbreak of WW I these objects with other valuable artifacts were taken to Moscow never to return.

Yesod also donated a two-tiered Baroque bimah with twelve columns: four Corinthian and eight Tuscan ones. Its design is sometimes attributed to the most popular Vilna architect of the 18th century, Johann Christoph Glaubitz. The depiction of the bimah by Franciszek Smugliewicz from 1786 shows a structure which differs from that captured on the photographs from the first half of the 20th century. Smugliewicz depicts the bimah as a canopy supported by twelve Corinthian columns and topped by twelve curved buttresses, thus alluding to the Temple of Jerusalem., though this drawing may not be precise.

Though It is customary to note that the Great Synagogue had around 3,000 places for the worshippers, this claim is wildly exaggerated. Judging from the numbers on the seats in the historical photographs, there were only about 450 seating places for men in the prayer hall, while the number of places in the women’s sections is unknown.

An two storey annex on the southwestern side of the synagogue contained the vestibule, known as the Polish, on in the ground floor and the Kahal Hall on the upper. In the late 19th and first half of the 20th century, two rooms of the Polish were used as a prayer hall, for unending prayer, where one minyan replaced another from sunrise until after midnight. A small room next to the Polish was used at the beginning of the 20th century as a gnizah (a repositry for old religious texts). The upstairs Kahal Hall included three rooms and a communal prison in the tower at the western corner of the Great Synagogue building, from which a winding staircase led to the roof. After the abolition of the Kahal in 1844, the rooms were used for various communal purposes. The Strashun Library occupied the rooms from 1892 until the erection of a separate building in 1902 when the rooms were transformed into an additional women’s section for the Great Synagogue.

The new building of the Strashun Library was constructed in 1902 on the southeastern side of the synagogue. It was built in place of the butchers’ shops erected in the mid-18th century by Yesod for the Tsdakah Gdolah Society. The new building, besides the library on the upper floor, comprised shops at street level.

In 1893-98 renovation works in the Great Synagogue were carried out. They included enlargement of the prayer hall by removing part of its northwestern wall and installing wide arches instead to separate it from the ground-floor women’s section. In order to receive permission for this reconstruction the engineer, Leonid Vilner, produced measured drawings of the entire building. A second detailed plan of the monument was produced in 1934 for the Institute of Polish Architecture at the Warsaw University of Technology.

The prayer hall of the Great Synagogue featured high Tuscan columns standing close together and reaching the spring of the vault, while the perimeter of the prayer hall was spanned by barrel vaults with twelve lunettes above the segment-headed windows. The lower tiers of the walls comprised segment-headed openings connecting the hall with several women’s sections situated in the annexes on the northeastern and northwestern sides of the prayer hall which were rebuilt in the late 18th century. Tuscan pilasters corresponding to the exterior ones divided the walls into bays; at some point in time, Corinthian columns were painted on those pilasters.

Already in March 1635 a Christian mob plundered the synagogue and consequent court files contain detailed descriptions of its furniture and chandeliers. An iron door leading from the polish (vestibule) to the prayer hall was donated by the tailors’ guild in 1640 and the door leading from the street to the polish - by the Magidei Tehilim (Psalms Sayers) Society in 1641. Fires of 1737, 1747 and again in 1748 damaged the Great Synagogue. The mannerist Aron Kodesh at the center of the southeastern wall was renovated by the Bedek Bait (Synagogue maintenance) Association after the fire of 1737 or 1748; a shield with the Tablets of the Law above the ark was donated by Yesod - Yehudah son of Eliezer. This shield, the doors of the Torah ark and the metal shell of the amud were rescued after the Holocaust and are today preserved in the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum. A large Menorah and a splendid chandelier were situated at the back of the prayer hall. At the outbreak of WW I these objects with other valuable artifacts were taken to Moscow never to return.

Yesod also donated a two-tiered Baroque bimah with twelve columns: four Corinthian and eight Tuscan ones. Its design is sometimes attributed to the most popular Vilna architect of the 18th century, Johann Christoph Glaubitz. The depiction of the bimah by Franciszek Smugliewicz from 1786 shows a structure which differs from that captured on the photographs from the first half of the 20th century. Smugliewicz depicts the bimah as a canopy supported by twelve Corinthian columns and topped by twelve curved buttresses, thus alluding to the Temple of Jerusalem., though this drawing may not be precise.

Though It is customary to note that the Great Synagogue had around 3,000 places for the worshippers, this claim is wildly exaggerated. Judging from the numbers on the seats in the historical photographs, there were only about 450 seating places for men in the prayer hall, while the number of places in the women’s sections is unknown.

An two storey annex on the southwestern side of the synagogue contained the vestibule, known as the Polish, on in the ground floor and the Kahal Hall on the upper. In the late 19th and first half of the 20th century, two rooms of the Polish were used as a prayer hall, for unending prayer, where one minyan replaced another from sunrise until after midnight. A small room next to the Polish was used at the beginning of the 20th century as a gnizah (a repositry for old religious texts). The upstairs Kahal Hall included three rooms and a communal prison in the tower at the western corner of the Great Synagogue building, from which a winding staircase led to the roof. After the abolition of the Kahal in 1844, the rooms were used for various communal purposes. The Strashun Library occupied the rooms from 1892 until the erection of a separate building in 1902 when the rooms were transformed into an additional women’s section for the Great Synagogue.

The new building of the Strashun Library was constructed in 1902 on the southeastern side of the synagogue. It was built in place of the butchers’ shops erected in the mid-18th century by Yesod for the Tsdakah Gdolah Society. The new building, besides the library on the upper floor, comprised shops at street level.

In 1893-98 renovation works in the Great Synagogue were carried out. They included enlargement of the prayer hall by removing part of its northwestern wall and installing wide arches instead to separate it from the ground-floor women’s section. In order to receive permission for this reconstruction the engineer, Leonid Vilner, produced measured drawings of the entire building. A second detailed plan of the monument was produced in 1934 for the Institute of Polish Architecture at the Warsaw University of Technology.

The Old Kloyz (Beit Midrash)

Tradition has it that the kloyz was established in 1440, though it was probably built in the late 17th or early 18th century. The Old Kloyz was heavily damaged by the fires of 1737, 1747 and 1748. The entrance to the kloyz was situated in the annex at the corner of the Great Synagogue and the kloyz. The inscription from the 1930s above the entrance door read: The Old Beit Midrash, established in 1440. The groined vaults of the prayer hall were supported by two Tuscan columns standing on the transverse axis; the bimah was placed between them. The Aron Kodesh was a simple yet beautifully ornamented.

In 1916 there were 27 regular worshippers in the kloyz, and five Talmudic scholars received a monthly stipend for learning there. The kloyz owned two rooms on the ground floor of the building and seven small rooms on the upper floor, and had gas lighting. The small number of worshippers in the kloyz in the 1920s and 1930s is the subject of Chaim Grade’s story Zeydes un eyniklekh (Grandparents and grandchildren). There was also a women’s section in the kloyz. The shtibl of the Lubavich Hasidim was also situated from the 1810s in the upper floor of the building, though these were used by the Tiferet Bahurim Kloyz from 1908.

The arched passages beneath the kloyz, leading to the second courtyard of the shulhoyf, were opened at the beginning of the 19th century, when the building was rebuilt in 1838.

In 1916 there were 27 regular worshippers in the kloyz, and five Talmudic scholars received a monthly stipend for learning there. The kloyz owned two rooms on the ground floor of the building and seven small rooms on the upper floor, and had gas lighting. The small number of worshippers in the kloyz in the 1920s and 1930s is the subject of Chaim Grade’s story Zeydes un eyniklekh (Grandparents and grandchildren). There was also a women’s section in the kloyz. The shtibl of the Lubavich Hasidim was also situated from the 1810s in the upper floor of the building, though these were used by the Tiferet Bahurim Kloyz from 1908.

The arched passages beneath the kloyz, leading to the second courtyard of the shulhoyf, were opened at the beginning of the 19th century, when the building was rebuilt in 1838.

The Chevra Kadisha Synagogue (Kabronishe Shul)

The Chevra Kadisha (Burial Society) in Vilna was probably established in the late 16th century, though its first explicit mention dates from 1655 and its prayer room noted in 1670. A separate synagogue with a women’s section of the Chevra Kadisha Kloyz existed already in 1707; half of its income belonged to the Tsdakah Gdolah (Great Charity) Society. The community transferred the synagogue to the exclusive possession of the Chevra Kadisha only in 1747 and erected there its synagogue in 1748. Following two fires Yesod paid for the construction of a new ceiling and received for this two burial places, for himself and his wife, in the cemetery.

The entrance to the synagogue was situated on the northwestern façade, facing the Old Kloyz, while the women’s section was entered through an outer staircase on the southwest façade. The Torah ark in the synagogue was an elegant masonry baroque construction, where two Corinthian columns flanked the Torah niche and bore a broken tripartite pediment. The wall above the ark was decorated with painted stucco rocaille. The photographs show that the windows of the women’s section were round-headed, while the windows of the prayer hall were rectangular. In 1915 electricity was installed for the 90 regular worshippers and 14 Talmudic scholars who received support from the congregation.

The entrance to the synagogue was situated on the northwestern façade, facing the Old Kloyz, while the women’s section was entered through an outer staircase on the southwest façade. The Torah ark in the synagogue was an elegant masonry baroque construction, where two Corinthian columns flanked the Torah niche and bore a broken tripartite pediment. The wall above the ark was decorated with painted stucco rocaille. The photographs show that the windows of the women’s section were round-headed, while the windows of the prayer hall were rectangular. In 1915 electricity was installed for the 90 regular worshippers and 14 Talmudic scholars who received support from the congregation.

The Shiv’ah Kru’im Kloyz

A small kloyz without a women’s section was established in the shulhoyf in 1747, on the ground floor of the building of the Hevra Kadisha Synagogue. The name shiv’ah kru’im means ‘the seven invited’ to read the Torah on Shabbat. Until 1919 this kloyz was used as the place where the Beit Din (religious court) held its meetings. In 1916 there were 32 regular worshippers and the kloyz had electric lighting. Chaim Grade writes in Der shtumer minyan (The silent minyan): “in no other kloyz in the shulhoyf did so many Jews pray as in the Shiv’ah Kru’im - a minyan after minyan until late into the night. Furthermore, there is not one piece of carving above the Torah ark and amud. In his novel The Agunah. Grade adds that, “The Shiv’ah Kru’im has no regular worshippers, only yor-tsayt Jews and mourners who come in order to say kadish; on weekdays as well as holidays several minyanim prayed there.”

The New Kloyz or the Kloyz of Yesod

The kloyz was established by the prominent philanthropist and merchant Yehudah son of Eliezer, known as Yesod. It was built in 1755-57 above existing one-storey houses, attached to the southwestern side of the Old Kloyz. Like the Old Kloyz, it was intended more for Torah study than for prayer; both kloyzn were connected through a single door, so that scholars could easily move from one kloyz to another. From the early 19th century a yeshiva was situated in the kloyz. The Torah Ark resembled that in the Chevra Kadisha Synagogue. It was flanked by columns in rococo style and its decorations reached the vault. Later, the vault and decorations were removed and only two lions above the ark remained. The low bimah railing was of wrought iron work plated with copper, so that it did not block the view towards the ark. In the northwestern wall of the kloyz there was a large window, which later was partly blocked by a women’s gallery. On the exterior, this arched window was emphasized by flanking pilasters and the walls were retained by buttresses.

In 1915-17 a kibbutz of Torah students existed in the kloyz. During WWI there were 26 regular worshippers, in contrast to 70 before the war. A marble plaque on the northwestern façade of the kloyz informed that the city’s Maggid Meir Noah Levin renovated the communal cistern, which was situated in front of the kloyz.

In 1915-17 a kibbutz of Torah students existed in the kloyz. During WWI there were 26 regular worshippers, in contrast to 70 before the war. A marble plaque on the northwestern façade of the kloyz informed that the city’s Maggid Meir Noah Levin renovated the communal cistern, which was situated in front of the kloyz.

The Gaon's Kloyz

The Beit Midrash of HaGra, the Gaon’s Kloyz, occupies the place of a building where the Vilna Gaon, Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman lived, in the shulhoyf, directly opposite the entrance to the Great Synagogue. In 1768 his wealthy relative Eliyahu Barats Peseles (d. 1771) bought the house, reconstructed it and on its first floor established a permanent minyan for the Gaon and his students. After the death of the Gaon in 1797, it was decided to convert his minyan into a kloyz. In 1799, after conflicts between the Gaon’s children and his students were settled in court and neighbouring apartments bought, the kloyz was established in this house. Russian official documents from the 19th and early 20th century name the kloyz as “the prayer house of the Famous Rabbi Eliash” or “Eliashevskaia prayer house.”

The Gaon’s Kloyz was one of the most prominent prayer and study houses in Vilna. Among many other outstanding personalities, Rabbi Avraham Danzig (1748-1820), author of Khayei Adam and father-in-law of one of the Gaon’s sons, used to pray in this kloyz. Jewish women used to come to the kloyz and pray at its Torah ark for the healing of their relatives.

The support to the Torah scholars studying in the kloyz came from the endowment of Yittzak Aizik from Hitovich made in 1801. By 1916 the kloyz owned several properties in the old Jewish quarter, including two shops and an apartment on the ground floor of its own building, and two apartments on the ground floor of the building of the New Kloyz. In the same year 13 prominent Talmudic scholars received a monthly stipend of 20 rubles for learning in the kloyz and the number of regular worshippers reached 50; this number was the same in 1935. Even benches there were made in a way convenient for study: the people sat back to back and each one had a shtender (lectern) for the book he was studying.

Initially the building of the kloyz was small and narrow; the drawing from 1834 shows it as a small two-story house. In 1855 the kloyz was enlarged by including a neighboring apartment. Finally, it was completely reconstructed upon the initiative of Yirakhmiel Broide in 1867-68. The southeastern street façade got a symmetrical composition: a central blank window, two wide segment-headed windows on its sides and two regular segment-headed windows on the edges. The gable with a central window and flanking oculi crowned the façade. The blank window, which marked the interior position of the Torah ark, bore an inscription in Hebrew: 'Beit Midrash / of the Gaon Rabbi Eliyahu / of the blessed memory, / established during his lifetime / in the year 1758 / and built anew / in the year 1868'. A similar inscription was placed at the entrance porch on the northeastern façade, opposite to the Great Synagogue. In the interior, the prayer hall was enlarged and its ceiling heightened. The new Torah Ark was flanked with two pairs of Corinthian columns. The ceiling was decorated with moldings and painted stars. The only known color depiction of the kloyz’s interior is a painting by Marc Chagall made during his visit to Vilna in 1935. He shows that the walls of the kloyz were painted green and the windows had red, blue and yellow colour glazing.

The place where the Gaon used to sit and study was marked by a wooden chest with a marble plaque above it at the middle of the northeastern wall. The decorated chest, which is today in the Spertus Institute in Chicago, was apparently made in 1868 bears an Hebrew inscription: ‘The place of the Gaon Rabbi Eliyahu, / may the memory of the righteous be blessed and last in the future world; / born in the year 1720, / on the first day of Passover / and passed away in the year / 1797, / the third day of Sukkot’.

The Gaon’s Kloyz was one of the most prominent prayer and study houses in Vilna. Among many other outstanding personalities, Rabbi Avraham Danzig (1748-1820), author of Khayei Adam and father-in-law of one of the Gaon’s sons, used to pray in this kloyz. Jewish women used to come to the kloyz and pray at its Torah ark for the healing of their relatives.

The support to the Torah scholars studying in the kloyz came from the endowment of Yittzak Aizik from Hitovich made in 1801. By 1916 the kloyz owned several properties in the old Jewish quarter, including two shops and an apartment on the ground floor of its own building, and two apartments on the ground floor of the building of the New Kloyz. In the same year 13 prominent Talmudic scholars received a monthly stipend of 20 rubles for learning in the kloyz and the number of regular worshippers reached 50; this number was the same in 1935. Even benches there were made in a way convenient for study: the people sat back to back and each one had a shtender (lectern) for the book he was studying.

Initially the building of the kloyz was small and narrow; the drawing from 1834 shows it as a small two-story house. In 1855 the kloyz was enlarged by including a neighboring apartment. Finally, it was completely reconstructed upon the initiative of Yirakhmiel Broide in 1867-68. The southeastern street façade got a symmetrical composition: a central blank window, two wide segment-headed windows on its sides and two regular segment-headed windows on the edges. The gable with a central window and flanking oculi crowned the façade. The blank window, which marked the interior position of the Torah ark, bore an inscription in Hebrew: 'Beit Midrash / of the Gaon Rabbi Eliyahu / of the blessed memory, / established during his lifetime / in the year 1758 / and built anew / in the year 1868'. A similar inscription was placed at the entrance porch on the northeastern façade, opposite to the Great Synagogue. In the interior, the prayer hall was enlarged and its ceiling heightened. The new Torah Ark was flanked with two pairs of Corinthian columns. The ceiling was decorated with moldings and painted stars. The only known color depiction of the kloyz’s interior is a painting by Marc Chagall made during his visit to Vilna in 1935. He shows that the walls of the kloyz were painted green and the windows had red, blue and yellow colour glazing.

The place where the Gaon used to sit and study was marked by a wooden chest with a marble plaque above it at the middle of the northeastern wall. The decorated chest, which is today in the Spertus Institute in Chicago, was apparently made in 1868 bears an Hebrew inscription: ‘The place of the Gaon Rabbi Eliyahu, / may the memory of the righteous be blessed and last in the future world; / born in the year 1720, / on the first day of Passover / and passed away in the year / 1797, / the third day of Sukkot’.

The Gmilut Chesed Kloyz

After the death of a brother of the Vilna Gaon, Issachar Ber, in 1807 his apartment near the shulhoyf was bought by an unknown philanthropist and converted into a kloyz in 1811. The same philanthropist established the Gmilut Hasadim Society which provided loans without interest and gave its name to the kloyz. The new building was erected in 1843 upon the initiative of Avraham ben Chaim Chayat. The name of the kloyz and the year of its establishment appeared on an exterior plaque, apparently marking the position of the Torah ark in the interior. By 1915 the kloyz had electric lighting and in 1916 there were 42 regular worshippers; the kloyz owned an adjacent apartment, which was rented out.

Apparently the Gmilut Chesed kloyz was beautifully decorated, its amud is made of stone, and its bimah stands stood between two thick columns.

Apparently the Gmilut Chesed kloyz was beautifully decorated, its amud is made of stone, and its bimah stands stood between two thick columns.

The Malaeske (Painters') Kloyz

A painters’ guild was founded in 1840 and its kloyz was first mentioned in 1862. It was situated in premises donated by Yosef Karpinsky. In 1916 the congregation numbered only 38 persons, though by 1933 the number has risen to 50. The kloyz had a wide window, a lantern and a women’s section. The interior was decorated by the Jewish painter Zinnmann with oil paintings of Biblical motifs - Noah’s Ark floating on the water; Abraham binding Isaac, Lot’s wife turning into a pillar of salt and a depiction of the Western Wall near the Torah ark.

The Chevra Poalim (Workers’ Association) Kloyz

The Chevra Poalim, which providing religious education for young Jewish workers and craftsmen was established by Avraham Tsvi Halpern in 1848-50, had a large kloyz on the first floor. It was built in 1875 and the women’s section was constructed in 1889. The interior placement of the Aron Kodesh was marked on the façade by a large pier with an oculus (or a blind round window).

In 1916 the upper floor of the kloyz was destroyed by fire. In the 1930s the kloyz was renovated and a new ark installed. The hall in the upper floor served in the 1930s for the activities of the Tiferet Bahurim Society.

In 1916 the upper floor of the kloyz was destroyed by fire. In the 1930s the kloyz was renovated and a new ark installed. The hall in the upper floor served in the 1930s for the activities of the Tiferet Bahurim Society.

The Hasidic, Koidanover or Liakhovicher Shtibl

Given the enmity that existed between the dominant Mitnagdim and the Hasidim, the earliest Hasidic minyanim had already appeared in Vilna in the 1790s. in the first the Karlin and Liakhovich Hasidim prayed and in the second the Habad or Lubavich Hasidim in the house of Meir ben Rafael in Evreiskaia (today Žydu) Street. At the same time the Hasidim tried unsuccessfully to take over the Old Kloyz.

The first permanent prayer house of the Liakhovich Hasidim in Vilna is mentioned in 1812. The Hasidic shtibl was built in the shulhoyf on the first floor and had round-headed windows around 1840 without a women’s section in which the Koidanov, Liakhovich and Slonim Hasidim prayed there. In 1916 there were some 100 regular worshippers.

The first permanent prayer house of the Liakhovich Hasidim in Vilna is mentioned in 1812. The Hasidic shtibl was built in the shulhoyf on the first floor and had round-headed windows around 1840 without a women’s section in which the Koidanov, Liakhovich and Slonim Hasidim prayed there. In 1916 there were some 100 regular worshippers.

Lubavich Hasidim Shtibl - Tiferet Bachurim Kloyz

The shtibl of the Lubavich Hasidim was mentioned in 1814 as existing on the upper floor of the building of the Old Kloyz. The prayer hall was entered through the entrance of the Old Kloyz, in the annex at the corner of the Great Synagogue and the Old Kloyz. The interior photograph from 1934 shows a column on the left of the Aron Kodesh, the metal railing of the bimah and a wall, covered with prayer plaques.

The Lubavich Shtibl was situated there until 1908, when the Lubavich Hasidim bought the Opatov’s Synagogue. Still, the premises of the shtibl above the Old Kloyz remained the property of the Lubavich Hasidim and was rented out to the Tiferet Bahurim Kloyz for 150 rubles a year. The Tiferet Bachurim Society was established in 1902 by the rabbi and pedagogue Yehiel Sroelov in order to attract young workers and craftsmen and to provide them with religious education. Lessons were held here in evenings and on Saturdays. In 1908 a separate kloyz was established in the former Lubavich Hasidim shtibl.

The Lubavich Shtibl was situated there until 1908, when the Lubavich Hasidim bought the Opatov’s Synagogue. Still, the premises of the shtibl above the Old Kloyz remained the property of the Lubavich Hasidim and was rented out to the Tiferet Bahurim Kloyz for 150 rubles a year. The Tiferet Bachurim Society was established in 1902 by the rabbi and pedagogue Yehiel Sroelov in order to attract young workers and craftsmen and to provide them with religious education. Lessons were held here in evenings and on Saturdays. In 1908 a separate kloyz was established in the former Lubavich Hasidim shtibl.

Other Kloyzn In the Jewish Quarter and the Ramales Yeshiva

The Jewish Quarter was home to many other kloyzn close by the Great Synagogue. These are only listed here to express the vibrancy of Jewish life in Vilna, but full descriptions can be found in the book ‘Synagogues of Lithuania’, details of which is noted below. Along Evreiskaia Street, later Zydowska Street and today Žydu Street was Leib Leizers’ Kloyz, the Tofrei Min’alim (Shoemakers’) Kloyz, the Blekher (Tinsmiths’) Kloyz, the Glaziers’ Kloyz, the Tailor Masters’ Kloyz, the Carpenters’ Kloyz, Parnes’ Kloyz, the Bookbinders’ Kloyz, the Chevra Torah (Torah Society) Kloyz, Dvora Ester or Shamashim Kloyz, the last three in the Ramayles courtyard with the Ramayles Kloyz which will be detailed below. In the adjacent Nemetskaia (today Vokieciu) Street was Mikhel Katsin’s or Zetel Kloyz. Behind the Ramyles courtyard was Miasnaia / Jatkowa Street, now named Antokolskio Street, which housed the Galanterey Kremer (Haberdashers’) Kloyz, Dachim Kloyz, the Urison or Tandetnikes’ (dealers in second-hand clothes) Kloyz (where Rabbi Israel Salanter founded his first Beit Musar in 1845), the Hakhnasat Orchim (Hospitality Association) Kloyz and the Daikhes’ Kloyz (Hat-makers’) Kloyz. In Stekliannaia (today Stikliu) Street in the centre of the Quarter was the Be’er Heytev Kloyz, the Kirzhner (Furriers’) Kloyz, the Tailor Workmen’s Kloyz and the Drukershe (Printers’) Kloyz. Dvortsovyi Lane, now Gaon Street and the continuation of Žydu Street, was home to the Bronznikes (Bronze Casters’) Kloyz, Shmuel Kliachko’s Kloyz, the Garbarske (Tanners’) Kloyz, the Tokershe (Turners’) Kloyz , the Felkremer (Leather Goods Retailers’) Kloyz, Beit Yaakov Kloyz, the Fisher (Fish-Mongers’) Kloyz and the Shtepershe (Stitchers’) Kloyz.

As we have noted, the Ramayles Yeshiva and Kloyz was located opposite the gates into the shulhoyf. This famous yeshiva, in fact the premier Yeshiva in Vilna, was established in the Gaon’s Kloyz in 1825 and moved first to the Tailor’s Kloyz and in 1831 to a building in the Reb Mayle’s (Ramayles) Courtyard where it stayed and acquired its name. The yeshiva building included a dormitory for students. In 1898 a tin roof was installed above the entrance to the yeshiva. In 1910 the building of the yeshiva collapsed, killing a woman. The yeshiva moved temporarily to a new house and then to new premises on Novgorodskaia (today Naugarduko) Street.

As we have noted, the Ramayles Yeshiva and Kloyz was located opposite the gates into the shulhoyf. This famous yeshiva, in fact the premier Yeshiva in Vilna, was established in the Gaon’s Kloyz in 1825 and moved first to the Tailor’s Kloyz and in 1831 to a building in the Reb Mayle’s (Ramayles) Courtyard where it stayed and acquired its name. The yeshiva building included a dormitory for students. In 1898 a tin roof was installed above the entrance to the yeshiva. In 1910 the building of the yeshiva collapsed, killing a woman. The yeshiva moved temporarily to a new house and then to new premises on Novgorodskaia (today Naugarduko) Street.

A Map of Jewish Vilna Prior to World War Two

Key

Railway

Bus Route

Bus Route

Public Bldg.

Monument

Church

(Cath., Prot., Orth.)

Synagogue

Church

(Cath., Prot., Orth.)

Synagogue

Kloyz

Jewish

Bldg.

Christian

Cemetery

Jewish

Cemetery

Jewish

Bldg.

Christian

Cemetery

Jewish

Cemetery

Small Ghetto

Large Ghetto

Large Ghetto

Click on Map to Enlarge

1 - Great Synagogue & Shulhoyf

2 - Jewish Quarter

3 - Gitke Toybe's Alley (Sv. Mikalojaus gatve)

4 - Old Ramayles Yeshiva

5 - New Ramales Yeshiva

6 - Vilna Rabbinical Seminary

7 - Hilf durkh Arbet Society (Trade School)

8 - Zalkind's Department Store & Palace Theatre

9 - Board of Rabbis, Herzl's meeting hall

10 - Dos Yisishe Folk Newspaper

11 - Founding place of the Bund

12 - HaOlam Newspaper, Kadima Publishing House

13 - Jewish Relief Committee (YEKOPO), Jewish Bank

14 - Romm press, newspaper & publishing house

15 - Kletskin Yiddish publishing house

16 - Vilna Jewish Teacher Traning Institute, Jewish

Museum, Vilna Jewish Community office, OZE

17 - Almshouse & Moshav Zkenim

18 - Meshmeret Holim Hospital

19 - Talmud Torah, ORT

20 - Folksteater

2 - Jewish Quarter

3 - Gitke Toybe's Alley (Sv. Mikalojaus gatve)

4 - Old Ramayles Yeshiva

5 - New Ramales Yeshiva

6 - Vilna Rabbinical Seminary

7 - Hilf durkh Arbet Society (Trade School)

8 - Zalkind's Department Store & Palace Theatre

9 - Board of Rabbis, Herzl's meeting hall

10 - Dos Yisishe Folk Newspaper

11 - Founding place of the Bund

12 - HaOlam Newspaper, Kadima Publishing House

13 - Jewish Relief Committee (YEKOPO), Jewish Bank

14 - Romm press, newspaper & publishing house

15 - Kletskin Yiddish publishing house

16 - Vilna Jewish Teacher Traning Institute, Jewish

Museum, Vilna Jewish Community office, OZE

17 - Almshouse & Moshav Zkenim

18 - Meshmeret Holim Hospital

19 - Talmud Torah, ORT

20 - Folksteater

21 - Hebrew Tushiya Gymnasium

22 - Gurevich Yiddish Gymnasium

23 - Epstein & Shpayzer Polish Jewish Gymnasium

24 - Mefitsey Haskala Elementary School

25 - OZE Health Organisation on Tzemakh Shabad

26 - YIVO, old building

27 - Lukiskes Prison (holding place for Jews prior to

transportation to Ponar for their murder during the Holocaust)

28 - The TsBK, Real Gymnazie. In WWII this was the Judenrat.

29 - Jewish Hospital (later included in Large Ghetto)

30 - United Partisan's Organisation headquarters

31 - YIVO, new building

32 - Kailis fur factory during WWII

33 - Baron Hirsch cheap housing. HKP camp during WWII

34 - Tarbut Hebrew Gymnasium. Today the Jewish Community office.

35 - Soup Kitchen. Maccabee sport's hall. Now the Gaon State Jewish

Museum.

36 - Taharot HaKodesh Syangogue (the only surviving synagogue)

37 - Old (Shnipishok) Cemetery

38 - New (Zareche) Cemetery

39 - Jewish Orphanage

40 - Moshav Zkenim (Old Age Home)

22 - Gurevich Yiddish Gymnasium

23 - Epstein & Shpayzer Polish Jewish Gymnasium

24 - Mefitsey Haskala Elementary School

25 - OZE Health Organisation on Tzemakh Shabad

26 - YIVO, old building

27 - Lukiskes Prison (holding place for Jews prior to

transportation to Ponar for their murder during the Holocaust)

28 - The TsBK, Real Gymnazie. In WWII this was the Judenrat.

29 - Jewish Hospital (later included in Large Ghetto)

30 - United Partisan's Organisation headquarters

31 - YIVO, new building

32 - Kailis fur factory during WWII

33 - Baron Hirsch cheap housing. HKP camp during WWII

34 - Tarbut Hebrew Gymnasium. Today the Jewish Community office.

35 - Soup Kitchen. Maccabee sport's hall. Now the Gaon State Jewish

Museum.

36 - Taharot HaKodesh Syangogue (the only surviving synagogue)

37 - Old (Shnipishok) Cemetery

38 - New (Zareche) Cemetery

39 - Jewish Orphanage

40 - Moshav Zkenim (Old Age Home)

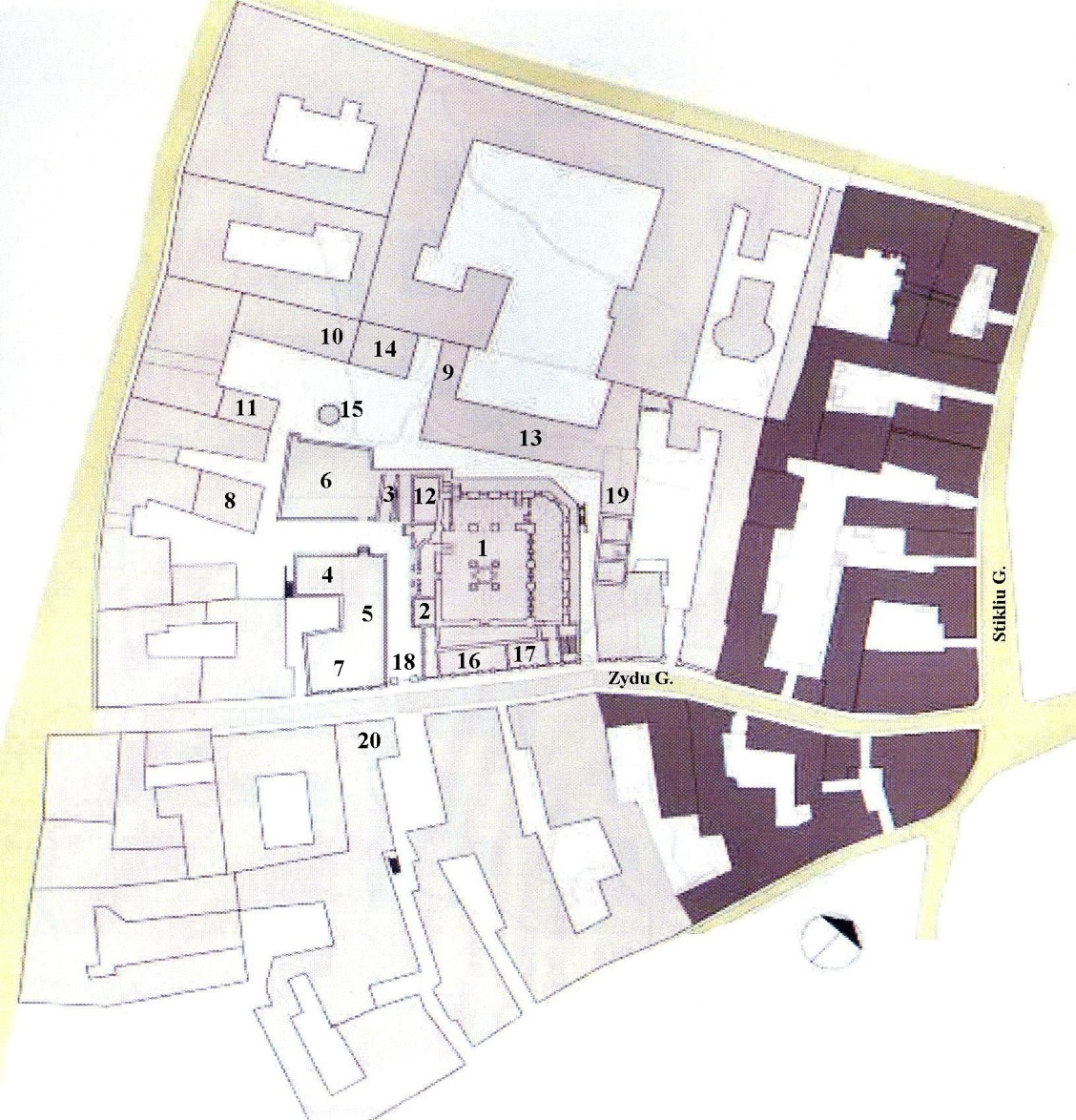

1 - The Great Synagogue

2 - Community Board

(kahal-shtub)

3 - Old Kloyz

4 - Chevrat Kadisha

Synagogue

5 - Shiv’ah Kru’im Kloyz

6 - New Kloyz of Yesod

7 - Kloyz of the Vilna Gaon 8 - Gmilut Hesed Kloyz

9 - Painter’s Kloyz

10 - Artizan’s Kloyz Chevra

Po’alim

11 - Koidanover Hasidim

Shtibl

12 - Lubavich Shtibl

13 - Bathhouse with

Miqveh (Ritual Bath)

14 - Public Lavatory

15 - Communal 'Well'

16 - Meat Stalls

17 - Strashun Library

18 - Shulhoyf Entrance

19 - Beth Midrash

20 - Ramayles Yeshiva

2 - Community Board

(kahal-shtub)

3 - Old Kloyz

4 - Chevrat Kadisha

Synagogue

5 - Shiv’ah Kru’im Kloyz

6 - New Kloyz of Yesod

7 - Kloyz of the Vilna Gaon 8 - Gmilut Hesed Kloyz

9 - Painter’s Kloyz

10 - Artizan’s Kloyz Chevra

Po’alim

11 - Koidanover Hasidim

Shtibl

12 - Lubavich Shtibl

13 - Bathhouse with

Miqveh (Ritual Bath)

14 - Public Lavatory

15 - Communal 'Well'

16 - Meat Stalls

17 - Strashun Library

18 - Shulhoyf Entrance

19 - Beth Midrash

20 - Ramayles Yeshiva

Plan of the Shulhoyf Buildings and the Great Synagogue

This site is best viewed in Internet Explorer or Firefox

Plan of the Great Synagogue of Vilna

The Shulhoyf

The Great Synagogue of Vilna

Inside the Great Synagogue

The Bimah & Aron Kodesh

The Strashun Library

The Kloyzn

The Old & Chevra Kadisha Kloyzn

The Old & Chevra Kadisha Kloyzn

Yesod Kloyz

The Gaon's Kloyz

After the Holocaust

Sources

Cohen-Mushlin A., Kravtsov S., Levin V., Mickunaite G., Šiauciunaite-Verbickiene J., 2012, Synagogues

in Lithuania , II, Vilnius Academy of Arts Press, Vilnius, Pp. 239-340

Guzenburg I. 2013. Vilnius. Sites of Jewish Memory: A Concise Guide. Pavilniai Publishers. Vilnius.

Cohen-Mushlin A., Kravtsov S., Levin V., Mickunaite G., Šiauciunaite-Verbickiene J., 2012, Synagogues

in Lithuania , II, Vilnius Academy of Arts Press, Vilnius, Pp. 239-340

Guzenburg I. 2013. Vilnius. Sites of Jewish Memory: A Concise Guide. Pavilniai Publishers. Vilnius.

[The Project] [Community] [Partners] [The Team] [The Vilna Gaon] [Previous Work] [GPR Survey] [Media] [Links]

.jpg)